Noted researchers in America are trying to find the answer …

Many of us have had a loved one – be it a parent, a grandparent, a dear aunt – disappear into that all encompassing Black Hole, that distant planet of Alzheimer’s. They may physically be with us but the essential person has vanished into a Never Never Land. They see you and yet they see you not. You are a stranger where once you were a part of their life. Unbreakable bonds between loved ones are severed and through no one’s fault.

Many of us have had a loved one – be it a parent, a grandparent, a dear aunt – disappear into that all encompassing Black Hole, that distant planet of Alzheimer’s. They may physically be with us but the essential person has vanished into a Never Never Land. They see you and yet they see you not. You are a stranger where once you were a part of their life. Unbreakable bonds between loved ones are severed and through no one’s fault.

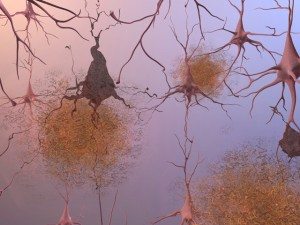

Indeed, patients with this devastating disease are like a tribe of lost people. Alzheimer’s destroys brain cells so that memories are lost: marriage vows, everlasting love all become illusions and relationships disintegrate.

‘Sometimes you have to let go of what you can’t live without.’ This is the tagline of ‘Away from Her’, the poignant film about the effects of Alzheimer’s on a marriage. This much acclaimed film touched a chord with filmgoers because it addressed a concern that is increasingly intersecting people’s lives as populations age. In it Fiona, played by Julie Christie, has Alzheimer’s and as she disappears bit by bit, she cannot recognize her much loved husband, and forms a relationship with a stranger in the nursing home.

Reel life is often reflective of real life. Recently we learned that retired US Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O Connor’s husband of 54 years, John, who has Alzheimer’s disease, had fallen in love with a fellow patient at the nursing home where he lives. His wife was happy for him, seeing him cheerful and comfortable.

Alzheimer’s changes lives in many ways: O Connor, who was the first female Supreme Court justice in the US, had retired in 2005 in order to oversee her husband’s treatment in a care center in Phoenix, and accepting her husband’s new relationship was just one more act of caring for her spouse.

“Our nation certainly is ready to get deadly serious about this deadly disease,” she told the Senate Special Committee on Aging and urged Congress to speed research.

Indeed, this ravaging disease is affecting more and more families, stealing memories, making people invisible and erasing meaningful lives lived, as if they never existed.

Alzheimer’s, which destroys brain cells and causes problems with memory, thinking and behavior, affects 5 million people in America and about half the population over the age of 85 in the US suffers from Alzheimer’s. By 2006 there were 26.6 million people worldwide living with the disease, according to the 2nd Alzheimer’s Association International Conference on Prevention of Dementia in Washington DC last year. This figure is expected to quadruple by 2050 to more than 100 million with 1 in 85 people worldwide living with the disease.

Alzheimer’s, which destroys brain cells and causes problems with memory, thinking and behavior, affects 5 million people in America and about half the population over the age of 85 in the US suffers from Alzheimer’s. By 2006 there were 26.6 million people worldwide living with the disease, according to the 2nd Alzheimer’s Association International Conference on Prevention of Dementia in Washington DC last year. This figure is expected to quadruple by 2050 to more than 100 million with 1 in 85 people worldwide living with the disease.

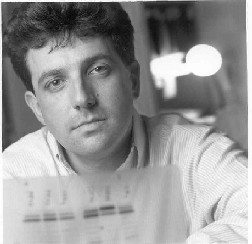

It is a disease without a cure and there is an accelerating worldwide effort under way to arrest this growth. There is a lot of research being done in the US, and we talked about these developments with Dr. Sam Gandy, Chair, National Medical and Scientific Advisory Council of the Alzheimer’s Association. He is also Sinai Professor of Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Professor of Neurology and Psychiatry, and Associate Director of the Mount Sinai Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center in New York City,

“It’s heartbreaking in almost every way you can think of,” says Gandy of the impact of Alzheimer’s disease. “Either the patients no longer recognize their children or spouse or they develop personality changes and become unmanageable or are institutionalized. It’s a very cruel disease.”

Gandy is an international expert in the metabolism of the sticky substance called amyloid that clogs the brain in patients with Alzheimer’s. In 1989, Gandy and his team discovered the first drugs that could lower formation of amyloid. He has written more than 150 papers, chapters and reviews on this topic.

In fact, Gandy has been in hot pursuit of amyloid since the 80’s. Ask him about it and he says, “Yes, that’s all we think about.”

“Alzheimer’s is the most common cause of late life brain failure,” says Gandy. “In about 3 percent of the cases it’s completely genetic and in those cases we are sure that the genes that are causing the disease had to do with the buildup in the brain of this gooey material which clumps and forms plaque called amyloid.”

“Alzheimer’s is the most common cause of late life brain failure,” says Gandy. “In about 3 percent of the cases it’s completely genetic and in those cases we are sure that the genes that are causing the disease had to do with the buildup in the brain of this gooey material which clumps and forms plaque called amyloid.”

As he points out, the pathology is identical and it looks just the same in the clinic and under the microscope but while the final common pathway is the same, researchers can’t be absolutely sure until they are able to develop an effective way of getting rid of amyloid.

Indeed, the good news is that many trials are being conducted, and among the most exciting are the ones which are aimed at preventing amyloids from building up or helping the brain to clear amyloids away. Gandy says there are three types of anti-amyloid drugs that are being tested. The first type of intervention is not really a drug but a vaccine so it is possible to either vaccinate people with the amyloid protein to make their own antibodies or else to make the antibodies in the laboratories and infuse them periodically, like chemotherapy.

The second type are plaque busters and involve medicine that keeps the amyloids from clumping, and the third is enzyme modulators which target enzymes called secretases; these enzymes make amyloid and some of them break amyloids down so the drugs either turn up the good pathway and cause amyloids to be broken down or they block the bad pathways and prevent amyloids from ever forming.

When can one see the results from these trials? According to Gandy, the results are starting to come through: the first plaque buster which was tested last year unfortunately failed, but progress is expected this year with the vaccine and one of the secretases modulators, a drug called Florizan.

“All of the drugs that are being developed for amyloids are totally unlike any other drugs that have been developed before,” says Gandy. “We’ve never tried to develop a way before to prevent amyloids from forming. So this is all very new territory.”

Asked about tests for Alzheimer’s, Gandy mentioned that the best way is still by basically undergoing a psychological test to see how the brain is functioning but new tests are on the horizon, brain scans that allow you to visualize Amyloid buildup.

He says, “ We hope that those will be available in a couple of years: until now we have been able to confirm the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s after death but if these scans hold up and are validated we will be able to potentially confirm the diagnosis during life and that will be a big help.

The scans will certainly tell us about the amyloids and we know that amyloid buildup is always part of the problem – we are not sure if sometimes there’s another process also going on that is both poisonous to nerve cells and gives off amyloids as a side reaction or side product. That’s the sort of alternative models we are investigating. We know amyloids play a role but we just can’t be absolutely sure if amyloids are the only thing going on.”

Researchers may be wrapped up in statistics and tests but often Alzheimer’s hits them on a personal level too. “It’s a very tragic disease – I’ve seen it not only as a scientist and a physician but as a family member,” says Gandy. “My father’s mother died of a dementing disease – probably Alzheimer’s – and I spent much of my life just watching her sort of slowly disappear. Even at the very beginning she lost the ability to recognize us and for 15 years we visited her every Sunday afternoon – and she had no idea we were there.”

The individual and the universal mix in this devastating disease and unless checked, Alzheimer’s could become the healthcare crisis of the 21st century. Researchers led by Ron Brookmeyer, PhD, Professor of Biostatistics and Chair of the Master of Public Health Program at The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, have created a multi-state mathematical computer model, using United Nations’ worldwide population forecasts and data on the incidence and mortality of Alzheimer’s. It is estimated that by delaying Alzheimer’s disease onset by one year the number of Alzheimer’s cases in 2050 could be reduced by 12 million.

“A global epidemic of Alzheimer’s disease is coming,” Brookmeyer says. “However, even modest advances in preventing Alzheimer’s or delaying its progression can have a huge global public health impact.”

Dr. Gandy paints a hopeful picture for the future: “We are developing these new medicines which we think will actually slow the progression and target the underlying genes and pathology. Most of what we know about the disease we’ve learnt in the last 20 years and just these genetic discoveries alone have made it possible for us for the first time to develop an animal with a model of Alzheimer’s on which we can test drugs.

Until 13 years ago there was no animal model of Alzheimer’s and we were just testing on models that were very remote. Now it’s possible to take a human Alzheimer’s gene and put it in a mouse, and the mouse will develop in its brain Alzheimer’s pathology and that’s how we test these medicines before we test them on people.”

© Lavina Melwani

Graphics and photo of Dr. Sam Gandy: The Alzheimer’s Association.

THREE WHO ARE FINDING A CURE

A coalition of leading Alzheimer’s disease organizations announced the first three recipients of “Tomorrow’s Leaders in Alzheimer’s Disease Research” prizes; a new award mechanism to recognize outstanding young scientists in Alzheimer’s and dementia research.

Sterling C. Johnson, Ph.D. – Associate Professor of Medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wisconsin, and Research Scientist, GRECC, William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, Madison. His research uses brain imaging in conjunction with neuropsychological measurement to study cognitive disorders of memory and self-awareness.

Dora Marta Kovacs, Ph.D. – Associate Professor of Neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, and Associate Neuroscientist, Neurology Service, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. Her research focuses on the molecular events underlying neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease.

James J. Lah, M.D., Ph.D. – Associate Professor in the Department of Neurology, Clinical Core Leader of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, and Investigator in the Center for Neurodegenerative Disease at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. His research is driven by the goal of understanding basic, disease-causing mechanisms to improve the care of individuals with neurodegenerative disorders.

(Source: Alzheimer’s Association)