‘The ‘Emperor of All Maladies’, subtitled A Biography of Cancer, won the Pulitzer Prize for Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee. This week it won the 2011 PEN/E.O Wilson Literary Science Writing Award. An interview with this award-winning author about the writing of the book.

Cancer Chronicles: Face to Face with Siddhartha Mukherjee

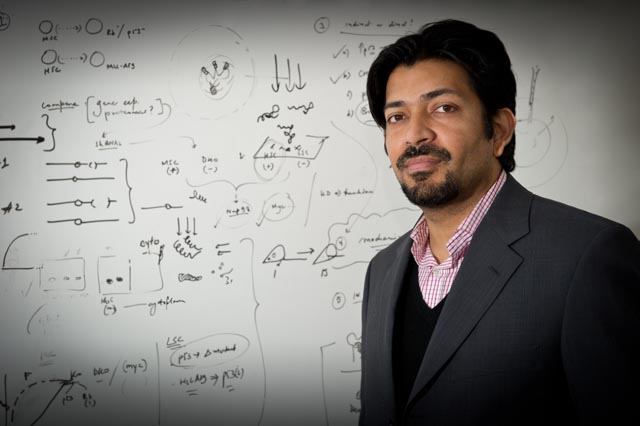

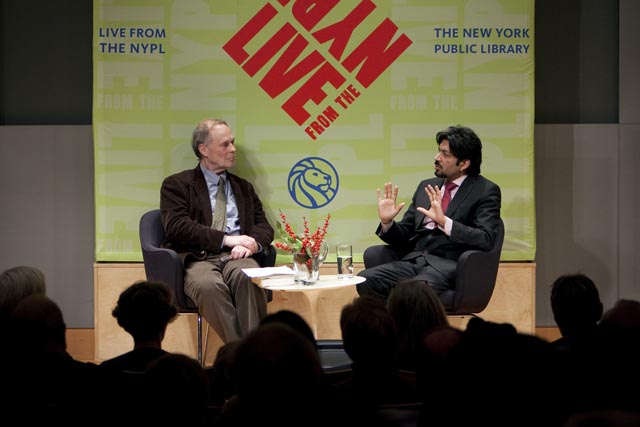

It’s not every day that you answer your phone and it’s a noted physician-writer on the other side. A Pulitzer Prize winner, no less! Ever since Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee’s ‘The Emperor of All Maladies’ was published, it’s become the hottest book around, and it’s been hard to get an interview with the celebrated author, as this leading oncologist and researcher has to fit in lab work, teaching, patients, media appearances and book tours into his busy day. Today he had conjured up the time as he was driving to the airport and had squeezed in this phone chat with me on the road.

So as Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee, known as Sid to those who know him well, drove to the airport in Miami, he talked about his book, his work, and his family for 40 minutes. Friendly and down-to-earth, he spoke easily about many things, almost regretfully telling me that his flight was boarding when our time was up. That evening I did get to meet him in person at an Indian gala in New York, and from the way the community gathered around him, you knew his was a star presence.

I asked him if he was surprised to get the Pulitzer for this first book. He replied matter-of-factly, “No one ever expects the Pulitzer.” Where was he when he first heard the news? He had just had lunch with Tina Brown, the editor of Newsweek, and was browsing in a book store in Tribeca. He bought a book of poetry by Kay Ryan, a writer whom he knew and who had just won the Pulitzer. On his cell phone, he saw a tweet about the Pulitzer Prize in his Twitter feed, and so clicked on it. His own name came up! He recalls, “I thought there was an error. I called my wife and I said can you please check? She checked and there it was!”

‘The Emperor of All Maladies’ has rightly been subtitled ‘A biography of cancer’ for this dazzling book turns cancer into something almost human, a real adversary to be fought and understood, strategized against and outwitted. The Pulitzer Committee called it “an elegant inquiry, at once clinical and personal, into the long history of an insidious disease that, despite treatment breakthroughs, still bedevils medical science.”

There weren’t any physicians or writers in Siddhartha Mukherjee’s family – his father Sibeswar Mukherjee was an executive with Mitsubishi and his mother Chandana was a school teacher. His parents still live in New Delhi, and Mukherjee recalls a home that was rich in the arts. “We spoke Bengali and English at home, our house was immersed in books,” he recalls. “I have a very intimate relationship with Bengali literature, particularly Tagore.” Music was another deep interest.

Mukherjee went on to become a Rhodes Scholar who graduated from Stanford University, University of Oxford and Harvard Business School. He’s been a Fellow at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute and an attending physician at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Business School. He is now an assistant professor of medicine at Columbia University and a cancer physician at the CU/NYU Presbyterian Hospital.

‘The Emperor of All Maladies’ – How the Book Evolved

His ground-breaking book evolved over ten years, starting out as a journal when he was a fellow in oncology, trying to get his bearings against an overwhelming disease. Mukherjee says you could say the book has taken a lifetime since a lot of it has to do with training and thinking about medicine, and writing about medicine. He adds, “If you are in medicine you figure out that actually there is kind of a complex structure that is going on underneath the book.”

Indeed, the book works on many levels, and is deeply layered so that it can satisfy those who know all the nuances of the medical world, and those who are entering it for the first time. The challenge, Mukherjee says, was not what to put in but what to leave out, as cancer is such a massive field and he did not want it to become a text book. There were tough decisions to be made on how to maneuver the space, on how to shape the story of cancer.

Ask him about the complexities of writing such an ambitious book, and he says, “Fortunately – or unfortunately, I am a very linear writer. I start on the first page, I end on the last page, not changing a lot of structure in the middle. In fact once I sit down to write, generally I am able to do it fairly fast.”

The challenge of ‘The Emperor of All Maladies’ was that in taking on such a formidable foe, Mukherjee had to create a complex tapestry which was by no means linear. It went all over the map, backwards, forwards, even sideways, zig-zagging between the impersonal and the very personal, between a clinical trial with 10,000 patients to the emotional tale of one particular patient. “The challenge was to take all that and make narrative out of it – it really is the most invisible thing in the book, it is the bones of the book,” says Mukherjee.

The book got written in fits and starts, mostly in the mornings and evenings, between work and family. Mukherjee is married to Sarah Sze, a MacArthur Genius award-winning sculptor whose work is in major museums and the couple has two daughters, Leela, 5, and Aria who is 18 months old. Fortunately for Mukherjee, his schedule is flexible. He sees patients one day a week, focuses on the laboratory research and writes both technical articles and his other writing. Reading and the arts are very much a part of his life, totally blended into his day. ‘Spare time’ is a concept unknown to him because there is hardly any! Into this crowded mix, is a collaboration with Standup to Cancer to make a documentary based on the book, and he is also in the early stages of his next book.

Battling Cancer

Cancer is such an imposing presence in so many lives that Mukherjee is always faced with people needing to know the answers at book readings and panel discussions. What ammunition does he suggest people adopt to safeguard themselves?

“The quick answer is that there is no single ammunition,” he says. “Part of what makes cancer such a formidable foe is that it is a complex disease with many major pieces and manifestations so I think that it really depends on a patchwork of prevention, treatment, surveillance, and understanding about cancer that ultimately will lead to longer lives, more dignified lives than possibly cure is for some cancers.”

Do South Asians carry any special risks for cancer and things they need to avoid? He points to tobacco use as one of the biggest risk factors that is not unique to South Asians but in fact has been prevalent all over the world, but happens to be particularly on the rise in developing nations. Cervical cancer is another disease that should be preventable through sexual education or through vaccination and it’s a matter of concern that young women are dying of cervical cancer.

“Similarly appropriate treatment and prevention of breast cancer should be something that is very achievable in India,” he says. “I am not talking about very extensive procedures or treatments, but relatively inexpensive ways by which we can change the landscape of cancer in South Asia. I do think that the evidence is there that more active tobacco control programs, more active vaccination programs for certain virally linked cancers would be very useful in South Asia.”

Finally, I had to ask – did he think there would be a cure for cancer in our lifetime? “Well I think there will be some cures for some cancers in our lifetimes,” he says. “I think more likely it will be about extending lives of men and women with cancer and perhaps turning cancer into a chronic disease. It really varies from one cancer to the other, as some cancers remain extremely intractable.”

Patients and their Stories…

Asked what came as the biggest surprise to him in all his research for his extensive biography of cancer, Mukherjee says it was the story of the patients and how deep their role was, and is, in this story.

“I wanted to move medical history away from the story of doctors and scientists and move it into the realm of the people who experience illness in the most proximal sense, that is the cancer patient,” he says. “It was most surprising to discover their stories and to learn how old that story was and how little has been known about it.”

These individual stories often do not have happy endings. How does a physician deal with the emotions of loss and death, and move on? To that, Siddhartha Mukherjee says, “I think physicians go through a grieving process like everyone else. It is important to grieve, it is important to go through the process of knowing a patient intimately because otherwise you are in the wrong profession.”

He adds thoughtfully, “So I think you deal with it like any other human being deals with it, by trying to find ways to resolve that grief. For physicians often the mechanism to resolve the grief is to dedicate your life more intensely to medicine.”

© Lavina Melwani

2 Comments

Thanks, Leena. I guess the Alexander McQueen exhibit will always be memorable to you not only for itself but also for the chance encounter with Dr. Mukherjee!

I had done another piece on him for another publication and will be sharing that soon. In fact, it’s a series of interviews with 5 noted writer-physicians.

As always, a wonderful article, Lavina! I love the fact that your website profiles Indian Americans that are “outside the box” and whose goals go beyond accumulating material things and superficial accolades.

I knew about Dr Mukherjee’s book since last fall, long before he became an international sensation. ‘The Emperor of All Maladies’ is a wonderful chronicle of the history, politics, science and economics of cancer in the past few thousand years. Only a genius like Dr M could have pulled off such an eloquent book on a complex topic like cancer – and I am so glad the Pulitzer committee recognized this!

Dr M has the extremely rare combination of intellectual brilliance and a heart of the deepest compassion coupled with the utmost humility and simplicity. He is a true gift to the field of medicine, the world and humanity. I am so fortunate to have bumped into Dr M over the summer while waiting on line for the Alexander McQueen exhibit at the Met.

He is quite a stunner!