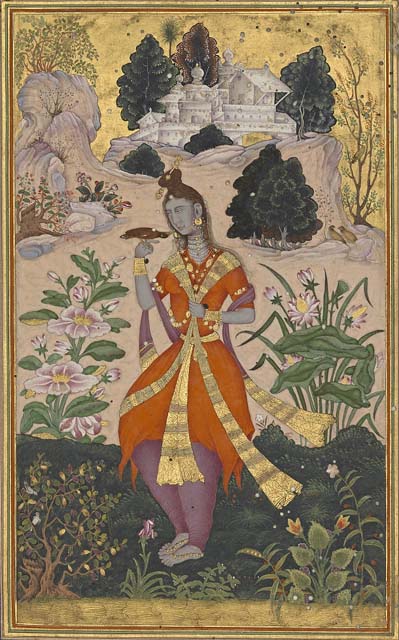

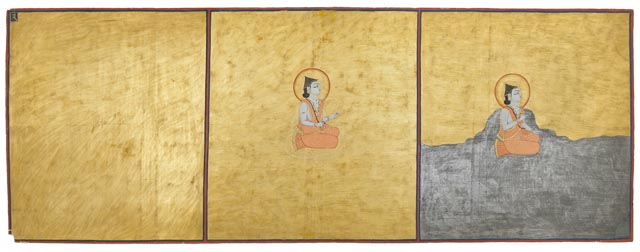

Three Aspects of the Absolute

folio 1 from the Nath Charit

Bulaki

India, Rajasthan, Jodhpur

1823 (Samvat 1880)

Opaque watercolor, gold, and tin alloy on paper

Mehrangarh Museum Trust RJS 2399

The Golden Age of Yoga

“But isn’t yoga an English word?”

This was the plaintive response one American had when she was told that yoga’s original birthplace was India. Indeed, this ancient practice from India has traveled so far and been so cut off from its moorings that many current day practitioners in the west seem to think it was always a part of American life.

Yoga has become a multimillion dollar industry with everything from yoga studios to yoga gear to yoga tourism. There’s even doga for dogs and yes, there’s chair yoga for older individuals and even baby yoga. For many in this commercialized, quick-fix world, yoga has indeed got cut off from its ancient roots.

Last year there was a comprehensive art exhibition in America, the first of its kind, which through the language of visuals – paintings, sculptures and photographs – traced yoga’s roots back to India, back to Gods and Goddesses, back to spiritual and philosophical aspirations. It was seen at the Cleveland Museum of Art from June 22 to September 7, 2014.

Yoga Narasimha, Vishnu in His Man-Lion Avata

India, Tamil Nadu

ca. 1250

Bronze

The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Dr. Norman Zaworski 1973.187

Narasimha – The First Yogi

After all, what can be more telling than seeing Narasimha, the mighty God Vishnu in his half man-half lion avatar, sitting in a relaxed asana, with a yogapatta, (known as a yoga strap to today’s yogis) around his crossed legs! Yoga Narasimha is a bronze Chola masterpiece from Tamil Nadu that dates back to CA 1250. The sacred text, Bhagavata Purana, relates that Vishnu came down to earth to protect his young devotee Prahlada and taught him Bhakti Yoga to make him invincible against his demon-father.

Yoga Narasimha is as far away as one can get from modern-day, strip-mall yoga but now’s a chance to get a darshan of this mighty yogi. Finally the dots are being connected between past and present with ‘Yoga: The Art of Transformation’ at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery at the Smithsonian in Washington DC. It brings over 133 rarely seen pieces of sculpture, paintings, and photographs gathered from 25 museums on three continents to trace out a visual history of yoga.

The exhibition was curated by Dr. Debra Diamond, Associate Curator of South and Southeast Asian Art at the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. After closing in DC, the exhibition traveled to San Francisco Asian Art Museum in SF from February 21 – May 25 and to Cleveland Museum of Art in Cleveland from June 22 – September 7. The accompanying catalogue has essays by noted scholars on several aspects of yoga, and offers many deep insights into the artworks.

Explorations with Debra Diamond…

A Dialogue About Yoga

“Deeply meaningful to Indians who cherish it as their legacy and to practitioners around the world who recognize its transformative potential, it also lies at the center of heated debates over authenticity and ownership,” notes Julian Raby, the Director of the Sackler and Freer Galleries of Art. “Shining a light on yoga’s manifold visual expressions, the exhibition does not define a singular yoga or determine authenticity. Rather, it aspires to enrich dialogue and inspire further learning about yoga’s profound traditions and enduring relevance.”

I traveled from New York to Washington DC to catch this exhibition firsthand and actually got the opportunity to see it in three different ways – once a walk-through with Dr. Debra Diamond and then on my own. I also joined a docent led tour for regular museum visitors so that I would get to talk to strangers who had come together to delve into 2000 years of yoga.

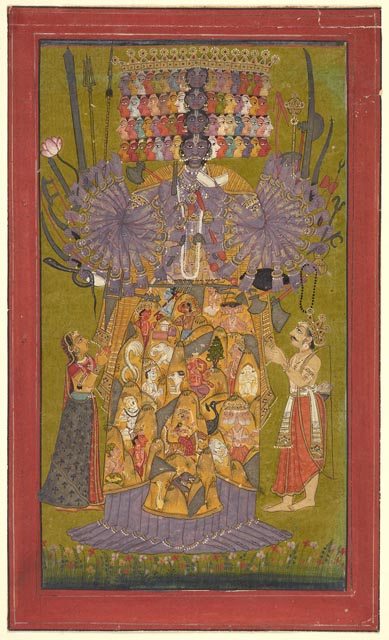

An introduction to Krishna Vishwaroop

Such has been the buzz in the media that thousands have visited the galleries. On this closing weekend the space was inundated with crowds, mostly westerners. When the docent asked how many practiced yoga, nearly all hands shot up. Yoga is indeed very much a part of American life and seems to have been proudly appropriated by all people. Some recalled learning yoga back in the fourth grade!

Bringing together these works of art under one roof was no easy task, taking over 5 years. It was indeed a labor of love for Diamond, who is herself a yoga practitioner. She says it was a huge scholarly enterprise which brought together experts from history, art, anthropology, religion and Sanskrit together to examine the rich archives of many museums. Diplomacy, advance planning and ample funds were required to borrow these great treasures. Even to move just one sculpture requires a courier to travel with it and insuring the art is very expensive. While the Smithsonian provides some funding, the majority had to be raised from corporations, foundations and individuals. Diamond also used the new method of crowd-funding where small online donations of even $25 from ordinary people can really add up.

Jina

India, Rajasthan, probably vicinity of Mount Abu

1160 (Samvat 1217)

Marble

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 2000.98

The Chariot and Horses of Yoga

Interestingly, the earliest literary references to yoga are found in the circa 15th century BCE Rig Veda and in that yoga meant neither meditation nor the seated posture but a war chariot yoked to a team of horses – the Sanskrit word yoga is linguistically linked to the English yoke, writes David Gordon White in his essay in the catalogue about the origins of yoga. The Hindu Kathaka Upanishad from third century BCE describes the linkage between meditation and the word yoga: “We read that the disciplined practitioner who has ‘yoked’ the ‘horses’ and ‘chariot’ of the body and senses with the ‘reins’ of his mind rises up to the world of the supreme god Vishnu.'”

With this exhibition, the story of yoga gets an enriched visual map. In her essay, Diamond explains: “Treatises and commentaries written between the third century BCE and the present day offer a coherent overview of yoga’s philosophical depth and developments. In contrast, objects and images foreground how yoga, despite the inherently individual experience at its core, has always been embedded in culture. Made by professional artists working for sectarian groups, royal and lay patrons, or within commercial networks, these artworks are situated at the interface of yogic knowledge and received visual traditions and the interests of diverse communities.”

Yoga’s beginnings are definitely in India but ranging from Hindu to Buddhist to Sufi, and in varied text and languages. As Diamond notes, “Created over some 2 millennia in diverse religious and secular contexts, these works open windows onto yoga’s centrality within Indian culture and religion, its philosophical depth, its multiple political and historical expressions, and its trans-sectarian and transnational adaptations. The pictorial tradition, which has never been holistically explored, reveals that yoga was not a unified construct or the domain of any single religion but rather decentralized and plural.” She adds, “While most objects emerged out of Hindu contexts or depict Hindu practitioners, Jain, Buddhist, Sikh, and Sufi images illuminate patterns of trans-sectarian sharing.”

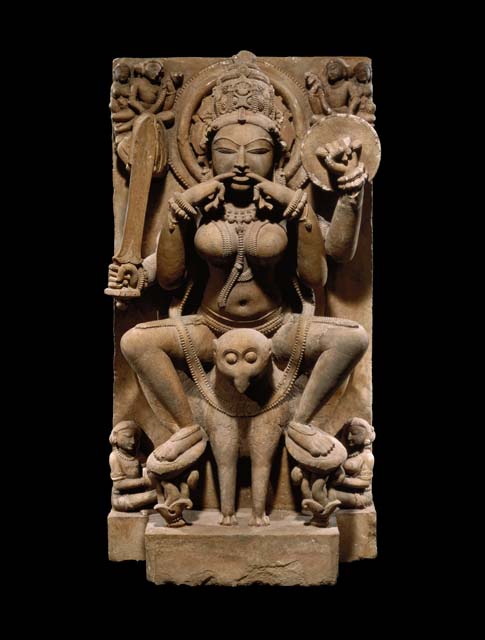

Women in Yoga

It is appropriate that in the very first gallery, the exhibition pays homage to the ancient divine and human teachers of yoga, emphasizing their role in spreading the tradition of yoga. A marble sculpture of a sublime marble Jina from Rajasthan, 1160, highlights the power of meditation. There are life-size sculptures of three fierce Tantric yoginis from a South Indian temple which was destroyed in the past, and the three have been reunited in this exhibit.

Yogini

India, Uttar Pradesh, Kannauj

First half of the 11th century

Sandstone

San Antonio Museum of Art, purchased with the John and Karen McFarlin Fund and Asian Art Challenge Fund 90.92

Yogis – Immortals with Unlimited Powers

The path of yoga is shown through manifestations of Shiva, Nath Siddhas, Jain and Buddhist yogis. Indeed, there are many artworks devoted to that great yogi – Lord Shiva. As the gallery highlighting the path of yoga shows, “the Hindu traditions known as Shaiva are based on the teachings of the deity Shiva; their texts are known as Tantras and Agamas. Bhairava and Sadashiva are two of the manifestations of Shiva. Three different sculptures showing Shiva as Bhairava. Yet another showing the Five-faced Shiva and Shiva as Sadashiva. Explains Diamond: “In the large corpus of texts known as the Bhairava Tantras, he reveals the teachings of yoga and prescribes initiation rituals in which adepts become immortals with unlimited powers.”

Sadashiva, one of Shiva’s most transcendent forms, figures in several Yoga traditions. Within the Agama texts of orthodox Shaivism (Shaiva Siddhanta) He is the supreme deity and a higher level of the cosmos in which there are no distinctions among person, body and world. His five heads represent five streams of knowledge ranging from the highest Siddhanta teachings to the least venerated Vaishnava Tantras.

The artworks that I found most compelling were four paintings gathered under the title of the Cosmic Body, depicting the ultimate reality which is the goal of yoga – the equivalence of the Self and the Absolute.

The striving of yoga practice is to become one with the vishwarupa, the ultimate cosmic form of the Supreme. The four paintings from the Northwest and Central India try to capture what ordinary mortals cannot even comprehend. Vishnu Vishvarupa (Rajasthan) is a breathtaking watercolor from Jaipur, ca. 1800-1820, which shows the cosmos within the Lord’s body.

Vishnu Vishvarupa – Vishnu as Cosmos

This small but powerful work shows Vishnu as the cosmos – “deities cluster in his upper torso, the phenomenal worlds are target like circles at his waist and seven demonic netherworlds are located along his legs.” Look into the sun and moon eyes of this blue-skinned Supreme Being encapsulating known and unknown worlds – and you get some idea of the depth of what true yoga tries to achieve.

Another painting from Bilaspur, ca. 1740, reveals the magnificence of Krishna Vishwarupa, who is known as Yogeshwara or the Lord of Yoga. Indeed, the Bhagvad Gita presents a spectrum of yogic practices and doctrines within a framework of personal devotion (bhakti) to Krishna. In this watercolor, the Lord reveals himself to Arjuna, the warrior prince, in his awe-aspiring Cosmic form with sixty multicolored heads and forty-four pinwheeling arms. The accompanying text helps us to understand the depth of the painting: “Within the golden dhoti that wraps around his waist, a miniaturized mountain landscape conveys – through the juxtaposition of scale – both Krishna’s vastness and his supremacy over all other Hindu gods and sages.”

Galleries devoted to Yoga in the Indian Imagination (1570-1830) showcase paintings and manuscripts created in Hindu and islamic courts. The earliest known treatise to illustrate yoga poses is the Bahr-al-Hayat (Ocean of Life), and ten folios from it can seen in the exhibit. Yoga and yogis were very much a part of life in ancient and medieval India and the richness of that depiction can be seen from many Hindu, Jain and Buddhist as well as Sufi and Mughal texts, folios and albums. There is a 12 foot long elaborate illustrated chakra chart or scroll from Kashmir (18th century) which lays out the 12 chakras and seven underworlds, and other yoga treatises which show the role of rulers in creating a visual archive of yoga.

Yogini with Mynah

India, Karnataka, Bijapur

ca. 1603–4

Opaque watercolor and gold on paper

The Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin In 11a.31

Yogis – wise, meditative, sinister, all-powerful

Yogis are seen in meditation but also in different aspects of life, playing music and in ashrams – and even involved in battle. Armed asceticism became increasingly common as sectarian identities evolved among yogis and they also battled over space and bathing rights. By the 18th century there were actually large armies of yogi mercenaries which were hired by Mughal emperors, Hindu Rajas and the British East India Company in their struggle for power. Battle at Thaneshwar, a bifolio from the Akbarnama by Emperor Akbar’s master artist Basawan, shows yogis wielding swords, axs and daggers. Yogis of different orders – Nath, Ramanandi and Sannyasi – are also seen in the Gulshan Album of Jehangir.

The exhibition shows the many images of yogis from the literature of the time – right from the Hindu epic Mahabharata to Tulsidas’ Ramcharitamanas, to the Mughal Albums of Akbar, Jehangir and Shah Jahan which are dazzling, exquisite art works. Yogis – wise, meditative, sinister, all-powerful are seen in ashrams and maths, practicing austerities, in pilgrimage and even in the cremation ground.

Folios from the Kedara Kalpa show yogis in pilgrimage and worship. Five Sages in Barren Icy Heights is an intriguing folio, ca 1815, which etches these five ascetics in the snowy abode of Shiva, examining and touching a large crescent moon, the emblem of Shiva.

The Ragamala paintings feature the renunciation of yogis as a foil to the allure of the materialistic life. In Bhairava Raga, from the Chunar Ragamala (ca. 1591) you have Shiva the yogi with ashes smeared on his body and a yogapatta around his legs, strumming on a veena, Around him are all the seductions of the material world. Writes Molly Emma Aitken about this painting, “At the heart of the painting, Shiva and his music tease mortals with a seemingly impossible collaboration between material desire and its transcendence that wells up again and again in India’s raga and ragini paintings.”

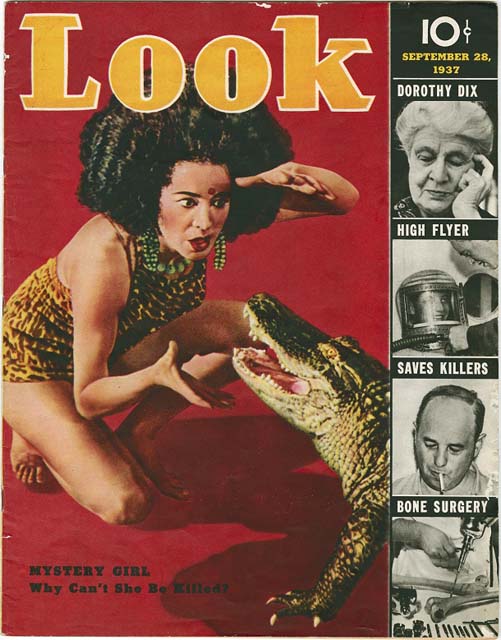

The Yogis in the colonial Gaze

Yet another gallery explores Yoga in the Transnational Imagination (1850-1940) the viewer quite a different perception of the yogi for with the coming of the British, yogis were vilified as exoticized beings in colonial photography and company paintings. There are stereotypical images of fakers and magic, of Hindu fakirs lying on a bed of nails. Constantly replaying in the gallery is Thomas Edison’s ‘Hindoo Fakir’ the first movie ever made of an Indian subject, and the infamous rope trick is part of it. This derogatory and Westernized image of yogis and yogas was perpetuated by mass photographs and postcards.

“Mystery girl: why can’t she be killed?”

Look Magazine, September 28, 1937

Des Moines, Iowa, United States

Private Collection

Globalized Modern Yoga

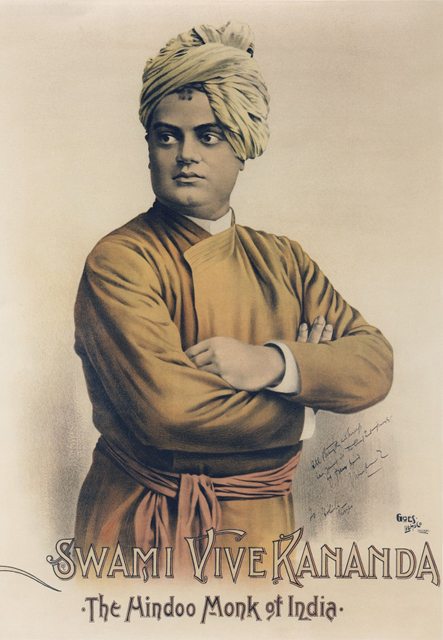

The exhibition also touches upon globalized modern yoga: an essay in the catalogue by Mark Singleton talks about how yoga was remade in the 19th century. “The reworking of the basic concepts and principles of Hinduism by certain sections of Indian religious tradition – a result of the encounter with new ideas and concepts from the West – is sometimes referred to as ‘neo-Hinduism’. The Bengali cultural association known as the Brahmo Samaj, founded in 1828 by Rammohan Roy repositioned Hinduism as a universalist, rational faith that could synthesize ancient Indian religious culture with the insights of contemporary science, philosophy and comparative religion.”

The final gallery revolves around the yoga renaissance of the late 19th and early 20th century with yoga being regarded as a nonsectarian practice for health and spiritual well-being. Here you find the books and images of Swami Vivekananda who brought a philosophically focused yoga to America. Visitors can also catch the earliest film of Krishnamacharya and his student B.K.S. Iyengar showing yoga postures, many of which are the basis of today’s yoga.

Having experienced this whirlwind tour of yoga through the ages, I chatted with an American yoga teacher who was visiting the exhibit with her students. Marsha Banks-Harold of Pies (Physical, Intellectual, Emotional & Spiritual )Fitness Yoga Studio in Alexandra, VA, said that they did do chanting at their studio along with meditation and asanas, and read from the Bhagavad Gita, while being accepting of all beliefs: “We are open to whatever each person brings to the studio. From our perspective we have to be open because we have people of different faiths. I believe the sutras say you have to be open to all paths and so that is what we focus on.”

Swami Vivekananda, Hindoo Monk of India

United States, Chicago, Goes Lithograph Company, 1893

Modern digital print of color lithograph

Vedanta Society of Northern California V22

Hinduism – The Wellspring of Yoga

Going into the exhibition I had wondered whether Hinduism would get the short end of the stick and not be recognized as the wellspring of yoga. While the galleries do speak of Yoga as an Indian phenomenon rather than solely a Hindu one, the works themselves are a powerful case of show over tell, for from the very first gallery you have Hindu gods and goddesses, mahayogis and yoginis as well as great Hindu texts powerfully and visually showing yoga’s origins. Hinduism is so complex with so many varied monikers as Shaivism, Vaishnava, Vedic, and Tantric attached to it that the single word Hindu is not always used.

Also, what becomes apparent as one browses the galleries is the truth that culture and religion are deeply entwined and exchanged in India, and Jain, Buddhist and Sufi artworks also highlight the prevalence of yoga in their traditions. There are sacred texts in a variety of tongues ranging from Sanskrit to Marathi to Persian, all a part of the 5000 year old juggernaut of Indian culture. The word Hindu is not always used but it’s interwoven into the fabric of India.

According to Diamond, this exhibition is only the beginning: four courses, in universities across the US, will be offering undergraduate and graduate courses in the visual culture of yoga: “It’s a new field and we happily anticipate many new discoveries about yoga’s rich meanings and histories,” she says.

Krishna Vishvarupa

India, Himachal Pradesh, Bilaspur

ca. 1740

Opaque watercolor and gold on paper

Catherine and Ralph Benkaim Collection

Yoga – An abundance of riches

Indeed, the show is a veritable feast of yoga knowledge on many levels and a gathering of masterpieces which will probably not be seen together again after this show. I saw many viewers examining the small paintings with magnifying glasses provided by the museum, for there are exquisite micro-details hidden in these works of art. An abundance of riches but in the end each person will take away only what they need or can comprehend.

“One of India’s greatest philosophers, Abhinavagupta, wrote in the 10th century that sensitive viewers – those who can literally taste the essence (rasa) of art – experience an aesthetic pleasure akin to the bliss of expanded consciousness,” writes Diamond. “Thus transcending the limitations of ego-bound perception, the sensitive viewer has a foretaste of enlightened detachment, which takes the form of “melting, expansion and radiance.”

The strength of this first exhibition of the visual aspects of yoga is that if you keep very still and immerse yourself in the magic world of these masterpieces, you lose sense of time, place and self. You feel the melting, expansion and radiance, and carry this affirming glow with you as you return to the train station of the mundane world.

(C) Lavina Melwani

This article was first published in Hinduism Today

Related Articles:

4 Comments

Via Google +

Parsotam Kachchhatia

+1’d:

Via Google +

senthilraja anG

+1’d:

Via Google +

Nitya Biswas and Mukesh Patel

+1’d: Imagine the story of #yoga through hundreds of masterpieces of #Indianart – divine!

Rahul Deokar via Google +

Inspiring tribute to a great journey…