3950 people saw it on FB Lassi with Lavina Page – https://www.facebook.com/LassiwithLavina

Indian art and Bollywood, Heroes, Heroines, Villains & Vamps

Bollywood may be loved by the frontbenchers in Indian cinema halls but it has friends in high places too – the elite world of contemporary art. There is just something about the surreal, over-the-top world of masala films and item dance numbers that strikes a chord in the more rarefied world of contemporary Indian art. A new show ‘Cinephiliac’ at Twelve Gates Art in Philadelphia, PA, checks out this phenomenon with the work of emerging as well as noted artists, a creative dialogue between art and film.

Indeed, this relationship is not new – art has been intermingling with Indian cinema since the beginning with those surreal posters and hoardings seen all over Indian cities. Bollywood posters have even become a collectors’ item, and many are the artists who’ve used Bollywood touches in their work. This new exhibition reinforces these influences and shows the work of both Indian and Pakistani artists, for the effect of Bollywood cheekily crosses borders and permeates different cultures.

As Atif Sheikh, the curator of the exhibition, points out, this show was the culmination of several interactions with works of or conversations he had with some of the artists in the show. Last year Daisy Rockwell and he shared thoughts about a Bolly/Lolly kind of show; she already had some work based on Bollywood.

Some time before that Professor Jamal Elias had mentioned this series of work he was planning to work on based on the iconic Punjabi film “Maula Jatt”. Maula Jatt went beyond being just a hit film, says Sheikh: “Its success, in a way, captured what the Pakistani society went through around the same time. Also last year I came across Murat Palta’s Turkish/Persian digital miniatures depicting scenes from classic Hollywood films such as Godfather, and Scarface. Palta’s work had taken social media with a storm. Suddenly everyone on my timeline was raving about his work and for good reason. His work is witty in an uncanny way and very creative.”

100 Years of Indian Cinema

Earlier in 2013 Sheikh came across Chitra Ganesh’s charcoal drawings based on film stills from early Indian films like Raja Harishchandra (1913) (now in Philadelphia Museum of Art collection), and Karma (1933). In an interview with Asia Society, Ganesh had mentioned that her film-series charcoal work also coincides with the 100 years of Indian cinema, since the first Indian film is widely believed to be Raja Harishchandra in 1913.

Sheikh adds, “That was the moment when I decided that we have these great ideas from all these artists whose work is directly related to cinema, its effects, and lure – why not bring them together in a cinema-themed show and what better time to do it than in 2013 marking Indian cinema’s one hundred years?”

Bollywood – A Parallel Identity

The eight artists in this show are from India, Pakistan, Turkey and the US. Is Bollywood very much a common phenomenon for them? Says Sheikh, “ What I particularly looked for while curating works for this show was something apart from pop-art celebrating celebrities, rather academic and art-historical perspectives. The last addition to the show was Salman Toor, whose work done in Rennaissance style is sometimes a social satire and critique of a culture that he is a part of. I can almost see the multiple perspectives he shows in his work, including my own as the audience-participant in the scenery.”

Most of the artists in the show are based in the US, like Leila Lal, Jamal, Chitra Ganesh, Ali Raza, Daisy Rockwell, and Salman Toor, who lives between New York and Lahore). Murat lives in Turkey and Summayya Jillani in Pakistan. All but Murat and Daisy Rockwell are South Asian by ethnicity but it is the subject matter that is common to all their work.

“Bollywood is a natural phenomenon for a large chunk of India and Pakistani Diaspora living in the US,” says Sheikh. ” It is sort of a parallel identity, almost stereotyping a diverse body of people. I would not say that Bollywood is a direct interest of the eight artists in the show but they all share a specific – and unique to each- interest in the influence of film on society and art, so in that sense it is a common phenomenon, and one that I as a curator sought.”

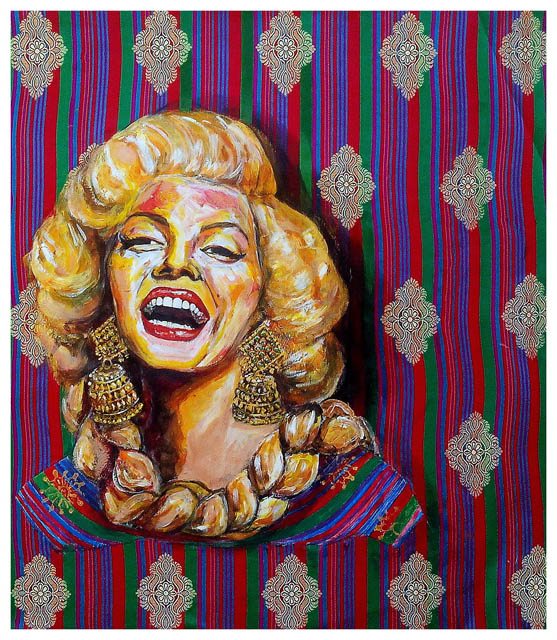

Asked about the inspiration behind these works, Sheikh says, ” Summayya Jillani’s Marilyn Monroes have, unwittingly, become the most identifying feature in her work. Jillani gives iconic treatment to the mundane in her other work; with Monroes she gave a native Pakistani treatment – local fabric prints – to a foreign idol.

Pop Culture & Cinema, East and West

Leila Lal and Ali Raza’s works are about the experience of cinema. The jewel-like shadow boxes with dancing girls’ pinup-style pictures comprise of 4 famous/iconic Indian actresses in their most famous roles. These poses, in lonely settings are, I reckon, what many people will identify with, as their dances are copied in the solitude of homes. Ali Raza’s work combines cinema’s motion with visual art in a very physical manner.”

In the work ‘Decent Couple’ one sees a reflection of Kajol and Shahrukh Khan, perhaps one of the most beloved pairings in Bollywood.

Describing his work, Salman Toor says, “With Pinkie and Decent Couple I was thinking about simple types of people in 90s and older Bollywood flicks, for example the villainess, the businessman with the spoiled daughter, the devout hindu mother, the hero etc. I wanted to link these types with social upward mobility of the middle class and upper middle class as I saw it in Pakistan.

I painted them in an effort to make icons of these templates. In Decent Couple I wanted to get to the heart of a matter in an imaginary, simplified love story involving Shahrukh Khan and Kajol: he offers her stability and security (as seen in the little melting house in his palm) and she shies away charmingly in a gesture of acceptance. Pinkie has a face based on the stock character of the villainess, the home wrecker, firestarter called Bindu who was very popular in the 70s.”

Peep Show series 2012 by Leila Lal

Desi Romance, tragedy and courtesans

As Leila Lal writes, describing her work: “What I am truly interested in with Peep Show 1 is the perpetuated sycophantic relationship contemporary society have with the nostalgic perception of courtesanship. This romanticized notion is particularly memorialized through Bollywood film, both old and new.

Films like ‘Umrao Jaan’, ‘Mughal-e-Azam’, and ‘Pakeeza’ (all referenced in Peep Show 1) were all romantic tragedies involving courtesans and men of power, and featuring these two archetypes as the heroine and hero respectively. Each of these types of films featured the Bollywood ‘it’ girl of the moment – an actress heralded for her sex appeal and unequivocal beauty (and perhaps with some actingskills). Peep Show 1 is not about examining the 15th, 16th, and 17th century role of the sexualized gaze, but looks further to the problematic nature of today’s viewership, particularly in light of the clear masochism that is so prevalent in today’s world.”

Pakistani Society and Cinema

Jamal Elias’ artist statement below gives a fascinating look at the nexus of art and cinema in Pakistan as he describes the 70’s in his country:

“The late 1970s represent one of the most defining periods in Pakistan’s history; it is no surprise, then, that it is also a significant moment in Pakistani cinema. The laissez-faire social attitude of the mid-70s came to an end when Prime Minister Z.A. Bhutto initiated apolicy of Islamization in order to shore up his waning popularity. The intrusion of religious values on the arts and on society at large increased with General Zia, Bhutto’s hand-picked military chief, who deposed and hanged him.

In the world of cinema, the period saw increasing censorship and a growth in vernacular culture, at a time that overlapped with the introduction of the VCR as the preferred medium of watching films among the Pakistani middle classes. The practice of viewing films while sitting at home in multi-generational, mixed sex family audiences reinforced a move away from the relatively sophisticated, sometimes adult themed, cinema of the 1950s and 1960s to an aesthetic that favored the “safer” subjects of comic book emotions, traditionally archetypal male (hero, villain, etc.) and female characters (e.g., heroine, vamp, etc.) and unrealistic violence. Such changes went hand in hand with a shift away from the use of Urdu – seen as literary and cosmopolitan — as the language of film to that of Punjabi, which is cherished for its rusticity and color.

‘Maula Jatt’ is the iconic film of this transitional moment. Released in 1979, it set records in theaters by running non-stop for two and a half years, and it made its star, Sultan Rahi, a legendary action hero. With deplorable production quality, writing, acting and direction, and its decidedly lowbrow aesthetics, Maula Jatt enjoys cult status in Pakistan to this day. This series of photographs draws on Maula Jatt to represent this seminal moment of transition in Pakistani cinema and society, in particular the increasing value given to uncomplicated and predictable vernacular representation at the expense of cinematic fare that had previously aspired to depict a refined national culture.”

(The show is on till December 15 in Philadelphia, after which there are plans to bring it to New York. More details HERE )

Related Articles:

South Asian Women Artists

Art tips for Collectors

Indian & Pakistani Contemporary Art

1 Comment

Pingback: Bollywood Meets High Art in Cinephiliac | Art Nerd New York