“Such is Kashmir, the country which may be conquered by the force of spiritual merit but not by armed force; where the inhabitants in consequence fear more the next world…Learning, high dwelling houses, saffron, iced water, grapes, and the like – what is commonplace there, is difficult to secure in paradise.”

– From the Rajatarangini, by Kalhana (1145)

In recent years, no doubt, it’s been a flawed paradise, a killing field where families have been torn asunder and homes lost forever. The timeless, idyllic place that visitors in happier times remember may well be lost, never to be experienced again. Yet there is a strength and beauty that lives on in the arts of diehard, resilient Kashmiris who, in spite of all the difficulties, continue to create crafts that blossom like the flowers of their native land. People outside Kashmir who only hear about the sorrows and bloodshed in this troubled vale had a chance to celebrate the hope of Kashmiris in a landmark exhibition at Asia Society showcasing its rich artistic traditions.

“The Kashmir Valley covers an area the approximate distance from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara, and at its widest point measures about 15.5 miles,” says Vishaka Desai, president of Asia Society. “Yet remarkably, despite its small size and a history of disruptive change over two millennia, the valley of Kashmir has remained a vibrant hub of intellectual and artistic activity for its Buddhist, Hindu, and Muslim populations over that long span of history.”

The Arts of Kashmir has objects dating from the 2nd to the 20th century, and those who do not know the history of this beleaguered land will be surprised to learn that many faiths flourished here; the exhibit includes works of Buddhist, Hindu and Islamic art – sculpture, painting and calligraphy – loaned from collections in the US, Europe and India.

It was an ambitious plan to gather Kashmiri treasures from many collections and the guest curator, a leading expert on Kashmiri art, spent six years selecting 138 pieces from 41 sources. Coordinating loans from so many sources was complicated, and working with a foreign bureaucratic system is always challenging since each country has its own system for granting the permission to loan art objects. The show now includes works on loan from the National Museum of India and the government museum in the Kashmiri capital of Srinagar—most of which have never before been seen outside the country.

Launching such a multidimensional exhibition was also a challenge and cost over a million dollars. “Right from the beginning, we wanted to work with both Muslim and Hindu communities of Kashmiris to help us develop a comprehensive cultural program to accompany the exhibition and raise much-needed funds to support our ambitious agenda,” says Desai. One may hear of strife in the valley but here both communities came together to fund this showcase of the arts of their homeland.

Asked about the most compelling pieces in the show, Adriana Proser, Curator of Traditional Asian art at Asia Society mentioned the sculpture of Ardhanarishvara, a half male and half female form of Shiva particular to Kashmir; the limestone Buddha from the Sri Pratap Singh Museum in Srinagar, which suggest some important visual links to Buddhist sculpture in China – a place monks visited Kashmir from so they could study Buddhism; she also points to the folio from the Gulistan with a portrait of calligrapher Hasain Zarin Qalam and Manohar, which shows the artistic impact of the Mogul emperors.

This exhibition shows the region’s extraordinary history as cultural and intellectual center. Buddhist, Hindu and Muslim patrons and artists were behind the production of a wide variety of art works, from sculpture and painting to metalwork and textiles. What one sees in so many of the works, whether from the 2nd century C.E. or the 19th century, is a range of converging styles and influences. This is a place of great physical beauty where amazing works of art, spectacularly crafted, were made for almost two-thousand years

In the beginning it was an important center for Hindu and Buddhist practice and philosophical development as some early pieces reveal. There is a 4th century terra cotta tile depicting crouching ascetics and birds from Harwan, which was associated with Buddhism. After the 7th century, a distinct Kashmiri style developed as shown in Dancing Mother Goddess Indrani, a large limestone sculpture with a distinct Kashmiri styling.

Later works show the refinement of this Kashmir sculptural style in an elaborate 9th century bronze mandala of Vishnu and 10th century Buddhist sculptures which show the Kashmiri mastery of metal casting and nuanced modeling.

Kashmir had rulers and religious institutions which patronized the artists and it was renowned as a center for Sanskrit learning and Buddhist and Hindu spirituality. Kashmiris worshipped Shiva, Vishnu and Devi but a number of sculptures demonstrate specific local attachment to the goddess Durga and the god of love, Kamadeva.

Kashmiri sculptors were commissioned by both kings and queens and by royal families and worked in familial groups in a variety of materials including marble, limestone, wood, clay and metal.

Alongside Hinduism, Buddhism flourished too in the Valley and surviving sculptures feature both Buddha and the Boddhisatvas. When Buddhism declined in Kashmir, many portable images were taken out and placed in monasteries in neighboring regions, and in this way the Kashmiri techniques and styles impacted other Buddhist communities.

With the advent of Islam, many Kashmiris converted and by the Mughal period, all signs of Buddhism had vanished and only a few Hindus maintained their faith and customs. From the 14th to the 19th century Islamic dynasties held sway and strong influences from Persia entered the artistic traditions of Kashmiri craftsmen. During the Mughal period Kashmir became a favored retreat for royalty and Kashmiri landscapes appeared in Mughal paintings.

Indeed, the Mughal period was one where four generations of Mughals – led by Akbar, Jehangir with his wife Nurjahan, and Shah Jahan and two of his children, Prince Dara Shikoh and Princess Jahanara – enriched Kashmir’s architectural heritage with secular and religious buildings and fabulous gardens.

It was also due to the Mughals and their mercantile activities from Europe to China that Kashmir’s famous shawls and crafts industries landed up on foreign shores. The Kashmiri traditions of paper mache, metalwork and painted, carved and lacquered wood continued to be patronized by the Mughal court, as well as the highly valued carpets and shawls.

Dr. Pal has written a scholarly book which gives a rich tapestry of facts about Kashmir’s arts and architecture along with photographs. One humorous tidbit from the book : “This greater Kashmir state was created in 1846 by a treaty between the British and Gulab Singh who was the Sikh governor of the territories. In exchange, Gulab Singh agreed to pay the British a lump sum of Re. 7,500,000 and an annual tribute of “one horse, twelve perfect shawl goats of approved breed (six male and six female), and three pairs of Kashmir shawls.”

Yes, the shawls were always in demand!

Later Sikh dynasties and British rulers supported many of the crafts the valley was renowned for. Interestingly, the presence of unique local motifs, such as the chinar leaf and the poppy pattern, is found across mediums as is the rosette or coriander flower. These have captured the imagination of artists everywhere and are present in the fashions of modern day India too. The innovative craftspeople are now also making cricket bats out of willow and these are much valued in the sports world.

And finally the carpets! Who has not admired the opulence of the Kashmiri carpets? Once again the Mughal emperors established Lahore and the Kashmir Valley as weaving centers where thousands of looms were constructed to supply markets at home and abroad. These carpets continue to fascinate today’s shoppers.

Ask Proser what she hopes visitors will take away from the show and she says, “A sense of awe for the works, and the artists and culture that created them.” Indeed, to see these treasures is to finally understand the true beauty of Kashmir and the resilience and God given talent of her craftspeople, their ability to create such beauty in the midst of chaos.

THE STORY OF THE SHAWL

No examples of Kashmiri shawls made prior to the 16th century have survived. However, the much-beloved Sultanate ruler Zain-ul-Abidin (1420-1470) was highly instrumental in promoting the textile industry, and his openness to new weaving techniques attracted artists from abroad to his industrious courts. It was probably at this time that the kani, or twill tapestry, technique used for shawls was adopted by Kashmiri artists. The technique is so slow that a complex design, produced before looms were improved in the 19th century, may have taken 18 months to complete.

Persian styles dominated shawl-weaving during the Sultanate (c. 1339-1525) and early Mughal period (1526-1858) The popular pinecone shaped motif called boteh which later became known as paisley, is a remnant of this Persian legacy. Despite the flourishing shawl industry under the Mughals,by the 18th century, Afghan rulers had imposed a heavy tax on shawl weavers that diminished productions considerably. It was revived by the Sikhs, whose tastes for bright shawls ushered in a stimulating period for elaborate and new designs.

The East India Company brought shawls from Kashmir to Britain in the mid-eighteenth century. However, their high cost and short supply led to cheaper imitation shawls being produced in Britain. The Universal Exhibition of London in 1851 featured shawls and carpets from Kashmir.

(Source: Arts of Kashmir)

(c) Lavina Melwani

Photos: courtesy Asia Society

Exhibition took place in 2007. Photo Details:

1. Embroidered shawl, decorated with a map of Srinagar

Kashmir

Late 19th century

Embroidered wool

L. 90 x W. 78 in. (228.6 x 198.1 cm)

Victoria & Albert Museum, IS. 31-1970

V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum

- Buddha with bodhisattvas and royal attendants

Kashmir or Gilgit (present-day Pakistan)

715 (dated)

Brass with silver

H. 14 1/2 in. (36.8 cm)

Pritzker Collection

© Hughes Dubois Brussels – Paris

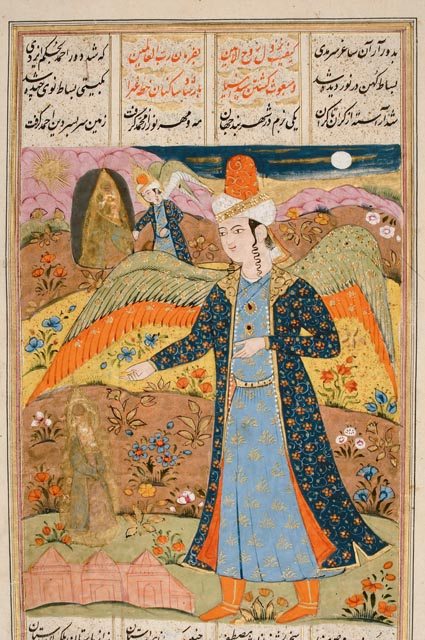

- The Archangel Gabriel [unidentified poetic chronicle]

Kashmir

18th century

Opaque watercolor and gold on paper

H. 9 17/32 x 5 21/32 in. (24.3 x 14.4 cm)

San Diego Museum of Art (Edwin Binney 3rd Collection), 1990:1467

San Diego Museum of Art (Edwin Binney 3rd Collection)

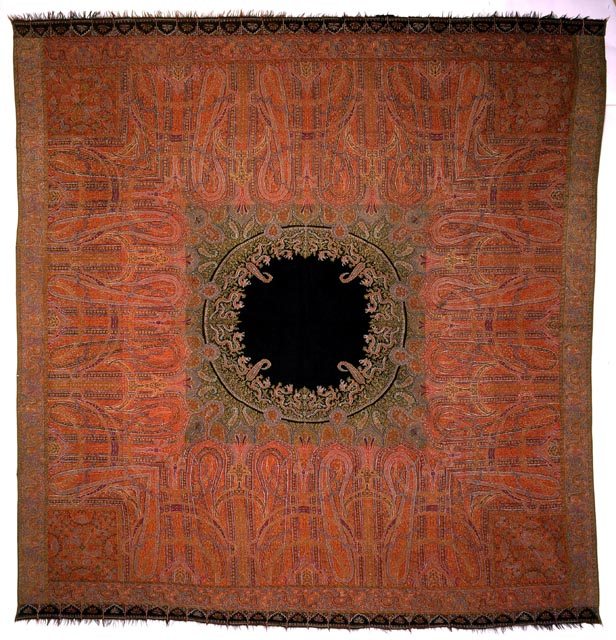

- Dragon shawl

Kashmir

Dogra period, about 1860

Woven Wool

L. 74 13/16 x W, 65 in. (190 x 165 cm)

15.6.1761

Private collection, courtesy of Simon Ray, London

Photograph courtesy of Simon Ray, London