2262 saw it on Facebook

Veekay Tejpaul, Sree Sreenivasan, Pallavi Shah and 18 others like this on FB Lassi with Lavina page

The Deccan Sultanate Shines at the Metropolitan Museum

We talk of today’s India as a great global power and of its international trade and cosmopolitan nature, but all this was already happening in India’s Deccan Plateau in the 16th and 17th centuries where, drawn by the access to port cities, diverse immigrants, merchants, mercenaries and missionaries from different parts of the world had landed, lured by the riches of India.

In the kingdoms of the Deccan Sultans there was a rich interaction with the Middle East, Africa and Europe, a buzzing trade in diamonds and textiles, and the flowering of a vibrant art and architecture scene.

“Asia and Europe met in the Deccan – it was where everyone was headed,” says Navina Najat Haider, Curator, Department of Islamic Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “It was where everything was happening so the Deccan is the absolute key to our world.”

This fabulous Deccani world can be seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York through a major pioneering exhibition, ‘Sultans of Deccan India: (1500-1700) Opulence and Fantasy’ (April 20- July 26, 2015) featuring over 200 of the finest artifacts, paintings, marbled drawings and textiles – not to mention superb diamonds – to evoke a world which has long since disappeared.

When the World Came to the Deccan

As Thomas P. Campbell, Director of the Met, notes: “Receptive to outside influences yet securely rooted in its ancient traditions, the Deccan become home to foreign immigrants, Sufi mystics, Shi’a Muslims and global traders. The courts of the Deccan kings also attracted artists from all over India and from further afield.”

This exhibition, curated by Navina Najat Haidar and Marika Sardar, Associate Curator, San Diego Museum of Art, showcases the courtly arts of the kingdoms of Bijapur, Ahmadnagar, Berar, Bidar, and Golconda, which drew great artists, musicians and writers, and produced uniquely distinctive art from its varied influences.

“Although the scale of the exhibition seems intimate – the journey was very long – it was almost ten years,” recalls Haidar. “We were traveling across the world, researching the subject, gathering the objects and understanding how to judge the material so as to bring the best and greatest things together as well as find new things that were not known – so it all took a lot of time.”

At that time, Haidar and her team were also working on the Islamic Galleries of the Met which house the permanent collection in the newly installed Islamic wing with art from the 7th to the early 20th century. She says, ” Working on the Islamic Galleries was very important actually because to fully understand the dimensions of the art and history of the Deccan it was useful to have the full background of the Islamic world. While Deccani art is an aspect of Indian art, it’s also an aspect of Islamic tradition, so keeping both those points of view together is what one needs to do.”

Golconda, ca. 1650–80

Cast, pierced, chased, and gilt copper, and brass

Dimensions variable

Collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase,

Friends of Islamic Art Gifts, 1995 (1995.258a, b); Private collections,

New York; Collection of Terence McInerney, New York; Collection of

Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, New York;

Indeed, a massive exhibition on this scale is quite unprecedented and this is a pioneering lending show with artifacts from over 60 -70 international lenders. Many of these items were separated for hundreds of years and are now in the same room once again, such as two water fountains, possibly from the same Deccani garden – one is now in Copenhagen, and the other in the collection of the Met. Haidar points out, ” Uniting pieces which were far-flung has been one end of the exhibition, to show the power of all these objects together.”

Many artifacts are from India, and some have never before left the country such as the crocodile from Bijapur which has been there since 1647, and is on his first foreign sojourn. This fish shaped water spout is from the Asar Mahal and has been loaned by the Bijapur Archeological Musum. Indeed, the loans are from diverse countries and negotiating them was a challenge, including a painting from Prague which has never before left the country, and getting that was regarded as a real coup.

So what can you expect to see at the show?

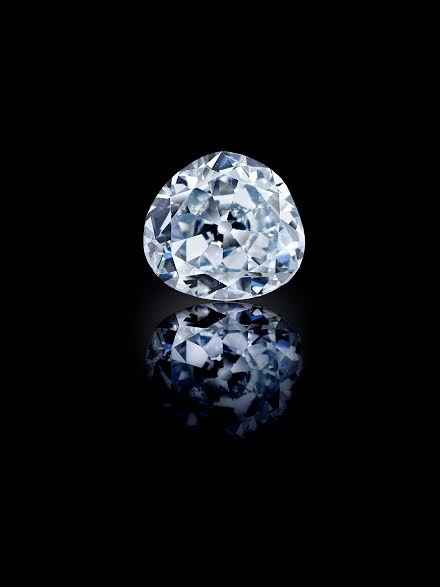

Idol’s Eye

Probably Golconda, early 17th century

Antique triangular modified brilliant-cut light blue diamond

H. 1 in. (2.6 cm), W. 1⅛ in. (2.8 cm), D. ½ in. (1.3 cm), Wt. 70.21 ct.

Al-Thani Collection

Image: © Servette Overseas Limited 2014. All rights reserved.

(Photograph taken by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd.

Diamonds and Much More

Of course, the diamonds are a big draw as the some of the largest diamonds came from the mines of Golconda, long before Brazil and Africa got into the action. The diamonds in the exhibition include the intense pink Agra Diamond, the brilliant blue Idol’s Eye diamond which in later centuries was turned into a Harry Winston necklace, and the fabulous Shah Jahan diamond which is shaped like an amulet or taviz.

The golden age of Bijapur under the rule of Sultan Ibrahim Adil Shah II was a celebration of arts and crafts, especially the bidri metalwork from the kingdom of Bidar. In every sphere of art, there was the freedom of imagination and this shows even in the intricate daggers of copper and gold which have carved interlocked animals in combat, and show many influences ranging from Chinese to Persian and European.

Dagger with Zoomorphic Hilt

Probably Bijapur, mid-16th century

Hilt: gilt bronze inlaid with rubies, blade: watered steel

L. 16½ in. (42 cm), W. 3⅜ in. (8.7 cm)

The David Collection, Copenhagen

Image: © The David Collection, Copenhagen (photographs by Pernille Klemp

A Celebration of the Arts

There are sumptuous royal objects made of inlaid and gilded metal, precious jewels, and stone architectural elements, many of which draw inspiration from the art of Safavid Persia and Ottoman Turkey. The kingdoms were also famous for the large painted and printed textiles known as kalamkaris, encompassing motifs from Indian, Islamic and European life. To look at these is to see the stories of those times unfold, with foreign emissaries surrounded by the color of India.

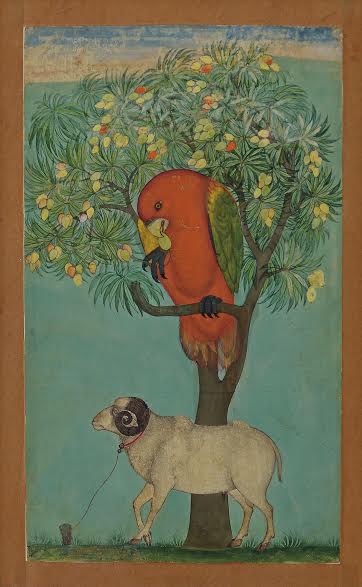

The Deccan Sultanates were specially celebrated for their paintings which evoke a poetic lyricism and were inspired by Hindu iconography, Persian and European paintings. These are small works but each of them holds a universe of meaning and style and ideas, according to Haidar.

A Parrot Perched on a Mango Tree, a Ram Tethered Below

Golconda, ca. 1630–70

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

9⅜ × 5½ in. (23.9 × 14.1 cm)

Jagdish and Kamla Mittal Museum of Indian Art, Hyderabad

(76.438)

“The view of Deccan art as otherworldly, as it is frequently described, certainly captures its most seductive qualities. Yet this perception has also partially eclipsed a full appreciation of the rigor and mastery of Deccani artists over the formal idioms of Islamic art,” she writes.

Haidar’s personal favorite is Wedding Procession of Sultan Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, dated 1650, an opaque watercolor and gold on paper, which shows a Hindu-Muslim wedding back in the 17th century, when a Golconda Sultan took a Hindu bride. The bride’s palanquin is empty because the groom has put her in front of him on the horse. “It’s a night time procession and it’s filled with mystery and magic and promise. For me, it shows this idealization of the coming together of communities and of traditions – it’s all beautiful and positive, and that’s what I love about this painting.”

Indeed, all these different cultures each made their contributions to the richness of the Deccan. “The interesting thing about the Deccan is like much of Indian culture and art in this period, it is very hybrid – it has a number of interwoven traditions – Islam, Hinduism and others – and its greatness arises from the fact that it empowers with the coming together of traditions. So I think we weaken ourselves as Indians when we start unpicking or picking apart the one thing that gives us the distinctiveness and strength which is the ability to amalgamate traditions into something even greater than the individual parts of them are.”

Many Cultures contributed to the richness of the Deccan

Calligraphic ‘Alam in the Shape of a Falcon

Golconda, 17th century

Perforated gilt copper

H. 13¾ in. (34.9 cm), W. 8 in. (20.3 cm)

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Image: © Victoria and Albert Museum

It was not a Hindu or Muslim conquest story…

As Haidar points out, the story of the Deccan Sultans was not a Hindu and Muslim conquest story even though in 1565 the five sultanates got together against the Hindu Kingdom of Vijayanagar. Previously, often rival Muslim kingdoms fought each other or allied with Vijayanagar. It was all very pragmatic and about self-interest. At the end of it all, the Deccan Sultans fell to the conquest of other Muslims, the Mughals, and this obsession for supremacy had a heavy cost for both, with the British waiting in the wings.

“The readings of history, and interpretations of history are always something to keep in mind, the record is open to discussion,” says Haidar. “It is also about shared culture that goes across bridges, across divides.”

Soon the Deccan Sultans faded into the mists of time but fortunately we can still view a rich sampling of their unique arts. ‘Fantasy and Opulence’ can be seen through July 26. This weekend, author William Dalrymple gave his own thoughts on the Asaf Jahi Nizams of Hyderabad to a packed auditorium at the Met. As he noted, the Deccan Sultanate had been relegated to just a few chapters in history books, but this remarkable, beautifully designed show draws it out of the shadows and showcases its spectacular achievements.

In this Internet age, the Met has truly gone global and the exciting thing is that whether you are in India or any other part of the world you can listen to the audio presentations and see the entire collection online. So the Deccan Kingdoms are as close as your computer, thanks to the Met. The exhibition is featured on the Museum’s website, as well as on Facebook

In the days of the Deccan Sultanates, it was the birds who were supposed to be very prescient. Now it’s a mouse – the computer mouse, which is omnipresent!

(C) Lavina Melwani

This article was first published in The Hindu

5 Comments

7 Google + on India Group

Vinod Mishra +1’d

SATYAM CH +1’d

amit singh +1’d

Karthick Seshan +1’d

Ganesh HariKumar +1’d

avijit mandal +1’d

suryakanta dash +1’d

Daniel EhnBom via Facebook

It is a splendid exhibition with old friends and new revelations.

Shago Perkins via Facebook

Wish I were there…

So glad you enjoyed the article – and the show! These objects were all in the same room together after many years. Quite a wonderful exhibition.

Thank you for the article, yes it was a world of refined splendor which people aren’t aware of – exquisite exhibition.