Discovering Little Jewels, with a magnifying glass…

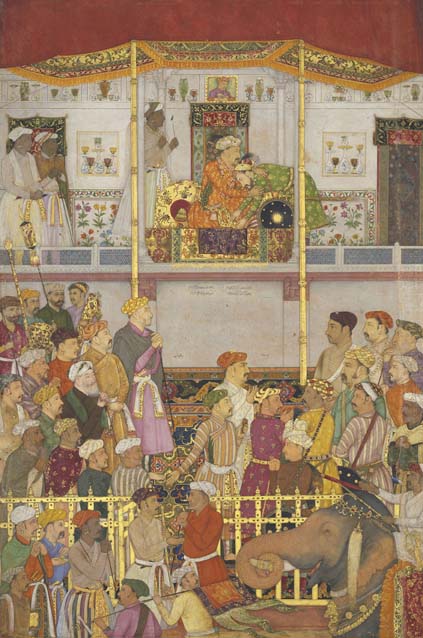

So let’s meet these artists and the fabulous works that they had created. You are surprised to see how small these works of art actually are, gleaming like little jewels. On the side of the room, there is a box full of magnifying glasses and you have to use one to really get the full impact and you realize these works were never intended for large audiences, but rather for the mighty Emperor and his charmed circle, for special royals to mull over in album form.

As you put the magnifying glass to your eye, small intricate details suddenly jump into view and you marvel at the intricacies of the stories woven into the landscape. There is a great pleasure in this as you feel that each discovery is your own. There is a feeling of interaction and intimacy.

Structured chronologically, the exhibition features the artistic achievement of individual artists in each period. As Roberta Smith wrote in The New York Times, “This show is not a coherent succession of gem-like Indian-painting bonbons. Things may cohere wall by wall, but turn almost any corner, or enter a new gallery, and you’re waylaid by a new personality or style or treatment of space — especially space.”

The exhibition takes us from manuscript painting of 1100-1500 to the early Hindu-Sultanate painting to the work of masters of the Dispersed Bhagavata Purana and the work of Baswan. In early Jain and Buddhist art there are no names for the artists but works which are by the same artist have been identified and brought together under given names such as the Mahavihaar Master or the Kalpasutra Master, a practice which is also common in European art.

The Golden Age of Mughal Painting is rich with the work of several artists who have now been identified, including Abd al-Samad, Manohar, Farrukh Beg, Keshav Das, Mansur, Balchang and Payag. There are also masters of the Chunar Rangmala, Nasiruddin, Hada master and the Kota School, as well as Early Master at the Court of Mandi. Each of their works is very individualized and offers interesting insights into their special contributions.

After the death of Jahangir, the accession of the puritanical Aurangzeb meant a death blow to art and the closing of the workshops. The lack of patronage led many artists to migrate to numerous courts in Rajasthan, and they took their Mughal training with them. As art suffered in the Mughal courts, it had a renaissance in the Hindu courts in Rajasthan and the Pahari area of Himachal Pradesh.

This is followed by late Mughal painting and the renaissance of the Hindu courts, with artists like Ruknuddin, the Nupur Masters: Kripal, Devidasa and Golu, Stipple Master, Bhavanidas and Chitarman II. After that is the period from 1730-1825, when artists like Mir Kalan Khan, Manaku and Nainsukh shone. Then came the first generation of Manaku and Nainsukh– Fattu, Khushala, Kama, Gaudhu, Nikka and Ranjha, as well as Purkhu of Kangra, Bagta and Chokha. The final galleries look at late court painting, company paintings and the advent of photography with artists like Tara, Shivlal and Mohanlal.