Riveting.

That’s probably the word one is searching for when asked about the new face of Pakistani art which is now being shown in art centers internationally. For a country in so much pain politically and socially – not to mention economically – Pakistan is surprisingly on top of things where art is concerned.

Art and artists have struggled and survived, art colleges have been nurtured and art galleries opened against a backdrop of partition, martial law, Islamization and the implementation of the Hudood Ordinance and the Law of Evidence, as well as war, terror attacks and economic struggles.

Yes, the art emerging from this turbulent space is surprisingly self-assured and confident, touching on topics which most wouldn’t touch with a ten foot pole. To take clichés a bit further, Pakistani artists are boldly rushing in where angels fear to tread.

There is a kind of honesty, a kind of eye contact which you don’t often get in the art world. These are canvases where you see the pain and the conflicts quite openly – and the frank commentary of these artists is like an open wound, for all to see. One thing is for sure, they are not afraid. And even if they are, they are bravely whistling in the dark, scattering the ghosts to the four corners.

While these artists have been working steadfastly in their home country through war, terror attacks and the slow disintegration of civil society, the larger world has finally started recognizing their presence. This year Asia Society launched the major exhibit “Hanging Fire: Contemporary Art from Pakistan” which received rave reviews.

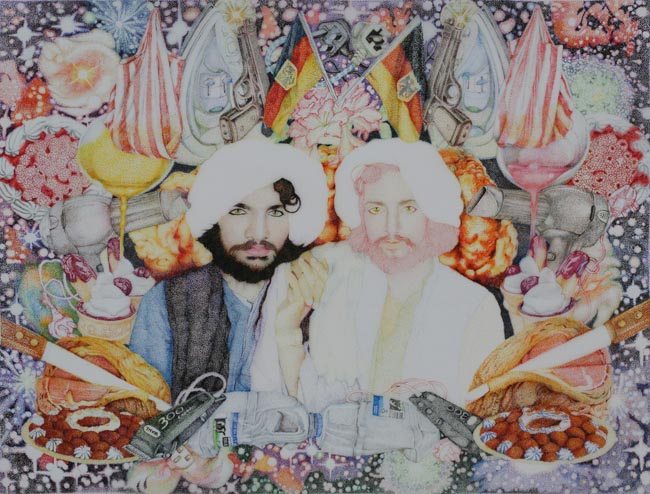

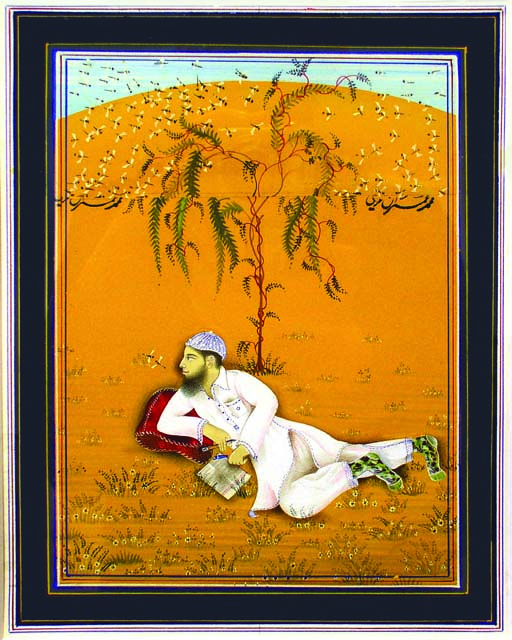

The show which can be seen in New York till January 2010 is the first major U.S. museum survey of contemporary art from Pakistan. It is curated by noted art scholar Salima Hashmi and spotlights the work of the late noted artist Zahoor ul Akhlaq as well as Hamra Abbas, Bani Abidi, Faiza Butt, Ayaz Jokhio, Naiza Khan, Huma Mulji, Asma Mundrawala, Imran Qureshi, Rashid Rana, Anwar Saeed, and Adeela Suleman.

“Despite Pakistan’s rich artistic and cultural history, most notably as a center of the Mughal courts, the country is all too often portrayed in the West in negative terms,” says Vishakha N. Desai, president of Asia Society. “Through this exhibition, we aim to address the critical need for deeper understanding of Pakistan’s diversity and complexity and to present a fuller picture of contemporary Pakistani society.”

As Melissa Chiu, museum director at Asia Society, points out, there is a new generation of artists in Pakistan who have created compelling works that have largely gone unnoticed outside their country. Indeed, she says that for these artists the highly charged socio-political context in which they live and work is critical to understanding their art.

Huma Mulji, an artist born in Karachi in 1970, perhaps puts this best as she describes growing up in a country which is a bundle of contradictions. “The irony of Pakistan simultaneously living three hundred years in the past and thirty years in the future, desiring to be at once the most forward-looking, and unable and unwilling to negotiate its traditional values with this idea of progress, is evident everywhere in the country. Yet, we are not comfortably pluralistic either. There are fantastic conflicts of taste, language, and images.” Old and new, past and present, the modern and the tradition juxtapose in her work. She says of High Rise: Lake City Drive, which psoes a bullock atop a neo-classical column: “It avoids the easy taking of sides in imaging a future urban landscape of Pakistan. It acknowledges the shades of gray evident in the complexities and ethics of mass urbanization and the quest ot realize the dreams of an aspiring, new, house-owning, suburban middle class.”

Yet another artist, Imran Quereshi, born in 1972 in Sind, brings this bold juxtaposition of old and new to the canvas, telling stories in the tradition of Mughal miniature paintings, with intricate details. the moderate Enlightenment series, made of thirteen figurative works, takes on social and political issues. There is mutiny and subterfuge too in his works. As he says, “The fashionable camouflaged socks worn by one one figure become a threatening gesture instead of a fashion statement. I have deliberately used three colors repeatedly in each of the works: red, white, and blue, inspired by the colors of the American flag.”

These artists don’t shy away from making political and social commentary, and gender inequities as well as women’s rights are all addressed in art. Salima Hashmi who is the Dean of School of Visual Arts, Beaconhouse National University, explains the arc of art development in Pakistan.

“I grew up in Lahore which was always a cultural hub,” she says, describing the city and the environment in which the art was created. “Music, poetry and to some extent art making was part of the life of the city.”

As she explains, the early modernists – sort of a parallel to the ‘Progressives in India – were allied with the writers of the day – and in fact some of them were poets and short story writers as well as painters: “So it was always a lively scene. Of course, Pakistan’s political history has influenced its creative output in all areas. Artists are notoriously ‘Bolshie’ everywhere, and they are no different here.”

Indeed, Pakistan’s checkered history since its birth in the throes of the bloody partition of undivided India makes fertile soil for the artist’s oeuvre. These conflicts and dichotomies are what these artists capture in their work, each bringing their own experiences into the convoluted mix.

“Responding to and working from their context makes these artists particularly interesting for the world right now, because people are mislead by the media which depicts us as a violent, muzzled, humorless society,” says Hashmi.

“The truth lies elsewhere….anyone who has danced to the sound of the drums at a Sufi Shrine on a Thursday, or rocked to the sound of music at one of the colleges in Karachi or Lahore, or gone to art school and vehemently debated issues in the studio, knows that this is a society of deep contradictions, full of energy and possibilities.. that is what informs Pakistani contemporary art.”

Aicon Gallery is one of the galleries in New York which has set the ball rolling for Pakistani art, opening the fall season with Farida Batool’s exhibition, ‘Ma Tujhe Salaam’ which takes its title from A.R. Rahman’s paean to the motherland.

“There is definitely a new awareness that is being generated around the contemporary art movements that are coming out of Pakistan,” says Priyanka Mathew, director of the Aicon Gallery. “There is a vibrant community of artists who are finally being recognized that is largely generated around the National College of Art in Lahore, the premiere institution for art in Pakistan.”

Batool, who was born in Pakistan in 1970, now lives in London but her homeland is a constant part of her art, for better or for worse. She portrays the harsh realities of today’s Pakistan because that is the world around her.

“Playing in the garden in my childhood with my cousins and sisters, I could not ever have imagined that the world out there would be so discriminating, harsh and intolerant,” she says. “The last few years have witnessed some very traumatic moments in our history where people have shown a lot of intolerance towards other groups, and one can only try to see the reasons behind it, but nonetheless, it makes one very sad and nostalgic.”

“I still carry within myself a sense of adventure, mystery, openness and generosity of people and also a sense of how with the passage of time, the essential characteristics of Lahori culture, which were tolerance, love for food, music, conversations has started to fade away.”

Growing up, she was told ‘nai reesan shehar Lahore diyan’ – there is no match for the city of Lahore and she would love to see that become a fact again.

“Farida’s works serve as metaphors for the political upheavals and tumultuous history of her country,” says Mathew. “They identify with the fear that is spread throughout Pakistan and the many citizens who have suffered at the hands of the changing regimes.”

In her work, the hanging male figure is not only a reference to the Taliban’s hanging of males in Swat but is also a reference to oppressive structures. Batool says, “Bhutto was also hanged and so are we in our daily grill. The pregnant belly is an obvious metaphor for motherland and it also reflects on the double standards prevailing in Pakistani society where women as mothers are given a lot of respect and even the homeland is designated as motherland – yet the rules and laws in that motherland are against these women and mothers.”

Priyanka Mathew says she is very moved by the work coming out of Pakistan for it has an honesty that is sometimes lacking in what she sees coming out of India. She recalls asking Salima Hashmi why and how so much rich and sophisticated work was happening in Pakistan, given the precarious political and social situations there.

“It is precisely because of the precarious situation there that there is a drive to express sentiments through art. It is the dire situation there that breeds these voices of dissent,” replied Hashmi.

As art thrives in the smoke and cacophony of everyday life being lived on the edge, a large number of emerging artists are being trained in over 30 art departments and art schools all over Pakistan. Says Hashmi, “They vary in quality and excellence, but it speaks volumes for the public acceptance of the activity and the profession. There is a growing market within Pakistan, still limited but expanding. The larger market in the area is of course India; collectors have been extremely supportive of Pakistani art and have been collecting widely and intelligently.”

The future looks promising for Pakistani artists – and by extension, for art collectors. These voices, emerging from the scarred underbelly of Pakistan, have been strengthened by conflict and turmoil and have an inner sense of self, even humor. As Pakistan’s story unfolds, it is the artists who will bear witness to its history.

© Lavina Melwani

Photos courtesy: Asia Society and Aicon Gallery.

RELATED ARTICLE: Painting Pakistan