Caught between the ebbing Mughal Empire and the rising British Raj, local Indian artists of that era painted a time of transition and served two masters. William Dalrymple and Yuthika Sharma examine a rarely covered period of Indian art history…

“Delhi was once a paradise,

Where love held sway and reigned;

But its charm lies ravished now

And only ruins remain.”

So wrote Bahadur Shah Zafar, poet and art patron, the last of the great Mughal emperors, as the mighty empire of his forefathers dissolved and the new rajahs arrived in town, the East India Company traders who were fast evolving into the new Colonial masters.

Those times are long gone, and Delhi, the spunky never-say-die city which re-invents itself after each invasion, is thriving once again. Yet, it’s intriguing to see what this city has gone through the ages. ‘Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi 1707-1857’, a recent exhibition at the Asia Society in New York allowed us to do just that with a showing of over 100 masterworks loaned from across the world, some of which have rarely been seen before.

The last days of the Mughal Empire were often thought to be days devoid of any artistic excellence, full of strife and political struggle as the East India Company rose to power in the last gasps of the Mughal Empire. Yet this exhibition emphasizes that it was a period of great artistic activity, a time of experimentation and innovation as the Indian artists produced works for their two patrons – Mughal nobility and the English residents.

Walk through the exhibit and your eyes take in these jewel like paintings and you enter a surreal world.

There’s the Nawab of Jhajjar astride a full-size pet tiger in his garden, surrounded by attendants.

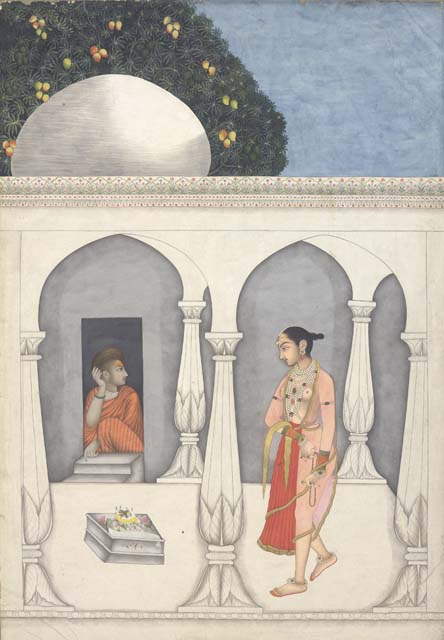

You see a Saivite woman entering a temple.

Then you have the Emperor Muhammad Shah, popularly known as Rangila (colorful), playing Holi with the women of his court.

And there’s Sir David Ochterlony in Indian dress, smoking a huqqa and watching a nautch performance in his residence.

These four images of Delhi encompass the different lives, the different stories that existed in the city at the same time, all painted by the Indian artists of that time. It was a period of complex artistic activity. A city in flux, facing changing fortunes, is shown through not only court art but also through sketches and architectural drawings of Delhi.

And who better to examine this churning of empire and Delhi’s ups and downs than William Dalrymple, the noted chronicler of the era, noted author of ‘The Last Mughal’ and ‘The White Mughals’? Together with art historian Yuthika Sharma, he has co-curated the Asia Society exhibition which focuses on the reigns of the last four Mughal emperors, Muhammad Shah, Shah Alam II, Akbar Shah II and Bahadur Shah II Zafar, a period from 1719 to 1857.

This exhibition came about through sheer serendipity. William Dalrymple was in New York in 2007 for a reading of his book ‘The Last Mughal’ which is about the great rebellion of 1857 and the Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar. Seeing the images of the art of that period, Vishaka Desai, the president of Asia Society, discussed the possibility of doing a show to highlight this little known art. At the recent opening of the exhibit, William Dalrymple observed, “It was a five year process between that first phone call and tonight.”

His co-curator in this venture is Yuthika Sharma, art historian, who was working on her PhD at Columbia University at that time. As she says, “The ‘Last Mughal’ was the starting point of an idea but when we got together, it developed into something completely different. What’s really exciting about this exhibit is that it’s the art of a transition period – and transitional periods are always very difficult to talk about.”

As she points out it was a period of political transition and while we know about that through current research, we don’t really know what happened to the art of that time. It was assumed that with the death of Aurangzeb, the Mughal atelier had ceased to exist.

” How do artists respond to change? ” she asks. “This is really about bringing to life a body of art that hasn’t been seen at all – it’s really talking about art in terms of continuity of tradition, continuity in artistic production. Here we are able to sketch this cultural continuity in a much more palpable way and we are able to give agency to the painters of this time. It’s about Indian artists and solely focused on Delhi as a site of artistic production, painting culture and the artistic milieu of this period.”

Asked if this art compared favorably with that of the earlier Mughal period, she said, “It’s more useful to talk of the art from this period on its own merit, for it really evolves into is its own kind of painting. This is about painters transforming methods of painting, this is about painters responding to various cultural stimuli and various patrons, and then modifying their techniques to suit a particular patron.”

It was a period of transition in art as different cultural worlds collided. As Dalrymple explained in an interview for Asia Society, “Artists at this period are experimenting mixing Western and Mughal traditions of painting: depending on their patron and what is required of them, they can do flat full frontal, in the Mughal tradition, or with perspective and shadow, in the Western mode. They can use watercolors or Indian stone-based pigments, and paint on cloth, wasli or watercolor paper. It’s a period of astonishing intellectual and artistic experimentation.”

The exhibition looks at works by court artists Nidha Mal and Chitarman, as well as Ghulam Murtaza Khan, Ghulam Ali Khan, and Mazhar Ali Khan. You see Mughal miniatures as well as Company School paintings done for Britishers like William Fraser, James Skinner and Thomas Metcalfe.

Indeed, it is the story of changing patrons. The Mughals, battered by loss of empire, had less finances to indulge in their role of art patrons. The painters, in need of work, were increasingly turning to the British officers and traders for patronage, and the so-called Company paintings came into being.

“The first British East India Company officials who settled in the melancholy ruins of Delhi were a series of sympathetic and notably eccentric figures,” write the co-curators of the exhibit. “Politically, they saw the value of the Mughal dynasty. Personally, they were deeply attracted to its court culture. The first British Resident, the Boston-born Sir David Ochterlony (1758–1825) set the tone, adopting Indian dress, marrying Indian women, fathering Anglo-Mughal children, and building the last of the great Mughal garden tombs for himself and his chief wife.”

One of his assistants William Fraser was also greatly enamored of the Indian art and lifestyle and became one of the important patrons, supporting the noted poet Ghalib as well commissioning pieces of art, including the Fraser Album worked on by Ghulam Ali and his family. This is considered a masterpiece and many paintings from this are in the show.

Interestingly here it gets personal, for William Dalrymple first got involved in a study of this period as his wife, the artist Olivia Fraser, is from the same family as William Fraser, and he first encountered his letters in the family library. These become the basis of much of Dalrymple’s work, and in fact William Fraser turns up in many of his books. He laughs, “So we have a strong personal connection. He seems to be a figure I can’t seem to shake off.”

Asked about it, Olivia, for whom Jaipur and Rajasthan have become a second home as a painter of miniatures, says about the William Fraser connection: “We have all his family papers in our library. We’re from the same clan – it’s quite Rajasthani, this idea of clans!”

Ask William Dalrymple which is his favorite painting in the exhibition, and he says, “The Fraser villages – every face tells a story. But then I’m totally prejudiced!”

And so that evening at the opening, hundreds of guests walked the gallery, examining long lost stories told through art. These paintings told tales of ambition, war, music and dance, stories of love and loss, monuments created and destroyed, stories of passions and pleasures.

Walking through the gallery on opening night, it was almost surreal to come across the iconic writer Salman Rushdie examining these paintings thoughtfully. This too could have been a moment frozen in time, a painting, a still life about stories and story-tellers, about how past and present blend together as we move into the future.

(C) Lavina Melwani

(This article first appeared in Housecalls Magazine)

The New Patrons: The White Mughals

“The Boston-born Sir David Ochterlony was twice British Resident (or ambassador) at the Mughal court in Delhi, and liaised with the Emperors Shah Alam and Akbar II. He was born in Boston, where his family fought with the losing British loyalists, and moved to India in 1777 after thePatriot victory at Yorktown. With his fondness for huqqas, nautch girls, and Indian costumes, Ochterlony cut a lively figure, amazing Bishop Reginald Heber, the Anglican primate of Calcutta, by receiving him sitting on a divan wearing a Hindustanijama and a turban, all the while being fanned by servants holding a peacock-feather fan (pankha). To one side of Ochterlony’s own tent, wrote Heber, was the red silk harem (shamiana) where his women slept.

Ochterlony’s cortege, which the bishop later spotted on the move through the country of Rajputana, was equally remarkable: “There was a considerablenumber of horses, elephants, palanquins and covered carriages,” wrote Heber. According to Delhi gossip, Ochterlony had no fewer than thirteen Indian wives; every evening during his years in Delhi he was said to have taken all thirteen on a promenade between the walls of the Red Fort and the river bank, each wife on her own elephant. Yet Ochterlony, like many figures of his age, lived a double life. By night, he lived in Mughal style with his Mughal wives, as seen in his celebrated image on view here, dressed in turban and kurta pajamas watching his dancing girls. Yet by day he upheld the prestige of the Company, fighting with distinction in the Anglo-Maratha war of 1803–5, and the Nepal War of 1815, as well as playing a prominent role in the Company’s political service.”

(Source: Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi)

The Last Atelier – Caught between two Worlds

Ghulam Ali Khan (active 1817–55)

The last great atelier of Mughal painting revolved around the family of one man, Ghulam Ali Khan. The artist described himself in an inscription on one of his most celebrated pictures, as “the hereditary slave of the dynasty, Ghulam Ali Khan the portraitist, resident at Shahjahanabad.” Elsewhere he signs himself simply “His Majesty’s Painter.”

Although Ghulam Ali Khan’s family were very proud of their status as hereditary painters to the Mughal throne, the truth was slightly more complex. The Mughal court no longer had sufficient funds to retain Ghulam Ali Khan exclusively, and to survive the painter had to moonlight as an architectural and portrait painter to several other members of Delhi’s high society made up of European officers, influential chieftains, and other regional rulers.

These included the Nawab of Jhajjar, who Ghulam Ali Khan painted astride his pet tiger. The painter also worked for several British patrons, including the Rajput-Scottish mercenary James Skinner and for British Residents at the Mughal court including William Fraser, who became the painter’s principal patron by the 1830’s. As Fraser’s purchasing power gradually eclipsed that of the Emperor, Ghulam Ali Khan and his family worked on the Fraser Album, the supreme masterpiece of the period.

In addition to Ghulam Ali Khan, we know of other members of the family who produced remarkable work in this period. The oldest, Ghulam Murtaza Khan, was the court painter of the penultimate Mughal Emperor Akbar II. He continued to work in the refined style of the seventeenth-century—his figures display a restrained naturalism reminiscent of the formality of compositions during the reign of Shah Jahan. The painter according to descendants was related to Ghulam Ali Khan, and was perhaps his father.

Another painter, Faiz Ali Khan who is the painter of two stunning group portraits on display here, was almost certainly Ghulam Ali’s brotherand with his son worked on architectural renderings for the British Resident, Thomas Metcalfe. Finally, Mazhar Ali Khan, a close relation, was primarily an architectural painter who produced the commissions from the last atelier including the great Delhi panorama for Metcalfe on view in this gallery.

(Source: Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi)

The Fraser Album of William Fraser (1784-1835)

When the wife of the new British commander in chief in India visited Delhi in 1810, she was horrified by what she saw there. It was not just the British Resident at the Mughal court, Sir David Ochterlony, who had “gone native,” she reported; his two assistants were even worse: “They both wear immense whiskers, and neither will eat beef or pork, being as much Hindoos as Christians.”

One of these men, William Fraser, a Persian scholar from Inverness who went on himself to become Resident at the Mughal court and lived in Delhi for three decades, made perhaps the most interesting journey of any British figure of the period, transforming himself from an self-exiled Scottish landowner to a White Mughal with an Indian family, a private army, and close relationships with some the most interesting artistic, theological, and political figures of the period.

Fraser became a crucial figure in Delhi’s artistic development: the Fraser Album, which he commissioned, was the landmark masterpiece of the period and its portraits of soldiers, noblemen, holy men, dancing girls, and villagers, as well as his staff and his bodyguards, are unparalleled in Indian art. Particularly remarkable are the images the Fraser Album contains of the village of Rania, some of which are on view here. Rania was home to Fraser’s mistress, Amiban, and his two Anglo-Indian sons, and daughter. Fraser’s connection to the village means that there is an intimacy here quite unlike the usual colonial commissions. The wild-looking and handsome villagers, superbly painted with a realist flourish by a master portraitist, were intimately known by Fraser, and formed part of his circle of acquaintances—as he wrote himself, the images recorded “recollections that never can leave my heart.”

(Source: Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi)