John Guy, Florence and Herbert Irving Curator of the Arts of South and Southeast Asia at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, talks about this major exhibition which showcases the work of 40 artists who are considered amongst the greatest in the history of Indian painting

Wonder of the Age – Master Painters of India

Q: Could you tell us about the steps leading to the exhibit ‘Wonder of the Age’?

A: For an exhibition of this complexity we had loans from about 30 lenders scattered across three continents, so it was a long and complicated process. The lead-time is around three years for projects of this kind, and involves discussions with various lenders about loans and whether these will be allowed to travel.

We then sit down for the serious business of cataloging the material and working on the catalog for the exhibition. The last year is increasingly taken up with insurance matters, indemnity, and securing of the loans. So it is quite an elaborate process involving many people across the whole museum – from curators to conservators to registrars.

Q: What was the most difficult aspect in your experience?

A: Often the most problematic is the fragile condition of the artworks, and so for the best of reasons some institutions were unwilling to lend works, as international travel is stressful on these works of art. I mean it is bad enough for humans but works of art suffer from changes in temperature, humidity, air pressure, and vibration. So some of the very important works we wanted to borrow didn’t pass the conservation test. One has to accept and respect this point of view and so that often complicates life. You have to go back and find other examples of high quality works by these artists and that can be very difficult for the pool of paintings you are drawing on for some of these early artists is very, very small.

Q: In all your research what were the aspects you were most impressed by?

A: This has been an unusual project because it involved the research of a team of over 20 people, all of whom wrote important chapters for a publication that was published in Zurich as a big two volume ‘Master Painters of India’ publication, which provides the background to the exhibition. It is far more encyclopedic than the exhibition could ever be, and includes many more works and more artists.

So many of those researchers brought new information to the field. We were delighted that at the Metropolitan Museum, we have a very important 12th century Pala manuscript on palm leaf and in the course of the research we were able to track down the name of the donor – a previously unrecorded Pala Queen. So we have a new name in the corpus of Pala royal figures. That discovery was very exciting but these are all too rare, I’m afraid.

Q: What was the hardest part of researching these artists?

A: Well, much of the serendipity is in asking the right question, being in the right place and some of it is just hard archival work, and one of the key figures behind this exhibition was Professor B. N. Goswami from Chandigarh, a very famous Indian art historian. Professor Goswami did much of the pioneering work on the artist Nainsukh from the Punjab Hills. He produced a monograph on this one artist a few years back which was a breakthrough for Indian art study.

We never had such a substantial study of one artist ever taken before, so this really was coming of age in this field of study. For that work he went through account books, pilgrim records, all sorts of archival documentation in palace archives particularly in Guler and Kangra and these places in Punjab hills and from that he managed to construct the life story of this painter, a very challenging thing to have undertaken and a very hard thing to achieve.

Q: Do you now have some idea of what the day-to-day life of these artists must have been like?

A: It is conjectural, isn’t it? With very flimsy sources you are trying to project back in time to have an idea of how things were at that point, and I think the reality is we don’t know too much about it. Goswami’s work on Nainsukh is the closest we’ll get to that. We know something about the lives of artists who worked within the Mughal ateliers and workshops because we have the whole series of very famous royal biographies, starting with Akbar’s Akbarnama and then Jahangir’s personal diary and then the memoirs of Shah Jahan. So all of these provide a lot of contextual information and you can envisage the setting in which these artists worked.

Q: So how would you compare these artists with the artists of modern India?

A: I think these artists were almost totally dependent on their patrons. They were paid employees of the prince or the ruler, while most artists today tend to be independent.

It is a very different mindset of course.

Q: Artists today have so much freedom to paint what they want, and often do social commentary in their work.

A: Yes, and sometimes they cross lines and situations change, you know. What M.F. Husain did 20 years ago caused no problems and you know when he did it five years ago, there had been trouble in Mumbai. That’s because of the changing landscape. He didn’t change but what changed was the attitude of the people looking at the works of art. And all this seen as blasphemous five years ago was not seen as blasphemous 20 years ago. That is just the different perspective people are bringing to the same subject.

Q: Will this process of identifying the artists be an ongoing one?

A: Absolutely, I mean there are already more artists identified than were in the exhibition, we had to be selective. And research continues – I am very much hoping the exhibition will be a stimulus to that and encourage younger students, particularly postgraduate students, to take up this subject and pursuit in postgraduate studies. There is much to be done in this field.

Q: What do you think is the benefit of being able to identify these artists?

A: I think it is a necessary stage to go through in the development of Indian art history studies to demystify the material, to actually link it to people. Once you start to identify enough individuals you start to see relationships between people. It is surprising in the show how many of the artists are related. Fathers and sons, brothers, cousins and so on and we know these skills were often hereditary and caste-assigned. It’s not surprising that these links are being identified and articulated for the first time.

Q: What do you hope visitors take away from ‘Wonder of the Age’?

A: We want to give a sense, an understanding that these works produced by anonymous craftsmen in dimly lit backrooms – these were very creative individuals responding to a particular place and time and their response to the subject matter and the demands of their patron – all those things went into the mix.

Related Article

Meet the Master Painters of India

(C) Lavina Melwani

(This article first appeared in Housecalls, India)

About the Images….

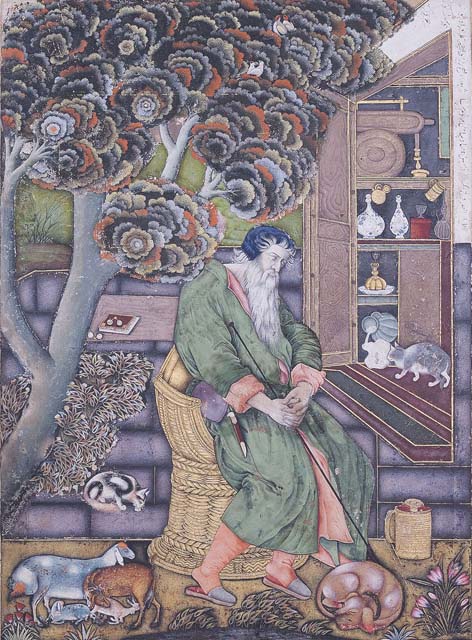

Farrukh Beg

A Sufi sage, after the European personification of

melancholia, Dolor

Mughal court at Agra

dated 1615

Opaque watercolor, ink and gold on paper

Painting: 7 5/8 x 5 9/16 in. (19.4 x 14.1 cm)

Page: 15 1/16 x 10 1/16 in. (38.2 x 25.6 cm)

Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

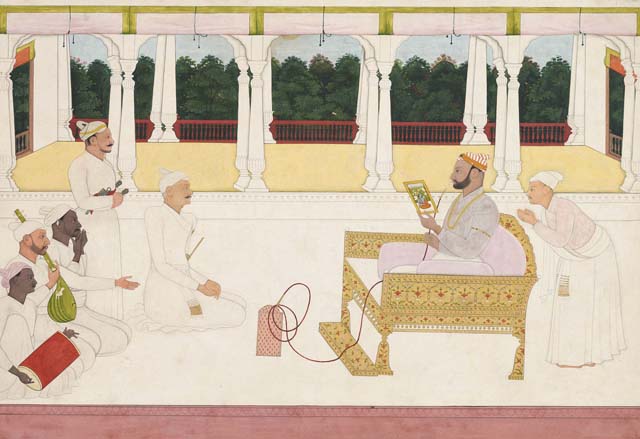

Nainsukh (Attributed)

Raja Balwant Singh of Jasrota viewing a painting

presented by the artist Nainsukh

Guler, Himachal Pradesh

ca. 1745 – 1750

Opaque watercolor and gold on paper

8 1/4 x 11 13/16 in. (21 x 30 cm)

Museum Rietberg Zürich, Gift of Balthasar and

Nanni Reinhart (RVI 1551)