Amitabh Bachchan is a 60-year-old married man in ‘Nishabd’, infatuated with an 18-year-old girl, the friend of his daughter.

Shakespeare’s Othello, with dialogues in Hindi, is transported to the Bihar badlands, in ‘Omkara.’

Aishwarya Rai, Bollywood Queen, stars in Rituparno Ghosh’s very un-Bollywood-type ‘Raincoat’ and Konkona Sen-Sharma, acclaimed for her performances in art house movies, acts in an out and out Bollywood biggie like Yash Raj Films ‘Aaja Nachle’.

Even a decade ago any of these happenings would have been a no-no in Bollywood. Yet, in the last few years a lot of unusual things have been happening in the Hindi film industry, and one can only expect more of the unexpected in 2008!

For years and years masala was not just something you added to your food – it was the name given to the genre of films which Indians watched avidly – a spicy blend of song, dance, comedy, melodrama, action and romance, with half a dozen song-dance scenes with as many costume changes in each. Indeed, that was what Bollywood fans really loved – you got life, love, smiles, tears, thrills and much, much more for your ticket – full value for your money!

It’s also true that once upon a time there was a golden period of Indian cinema, the era of greats like Bimal Roy, Raj Kapoor and Guru Dutt, but since the 70’s the industry had been mired in a kind of masala quicksand, barring some notable exceptions.

In the past few years, however, we’ve been seeing a kind of re-focusing, a fine-tuning where a Hindi film is not everything-and-the-kitchen-sink, with a new emphasis being given to narrative, rather than hackneyed plots which you could follow with your eyes closed. We’ve all seen our share of twins separated at birth and sons avenging their parents’ deaths at the hands of diabolic villains!

In the last decade, audiences have seen the emergence of slick comedies, horror films, murder mysteries, sci-fi, ensemble movies and a whole lot more from innovative young directors like Mani Ratnam, Ram Gopal Varma, Sanjay Leela Bhansali, Vishal Bharadwaj and Karan Johar. There have been films with hardly any songs, and others with lots of songs; films with unknowns and films with a whole phalanx of top stars; movies with very real stories and movies with absolutely surreal stories. You can almost rattle off the names of noteworthy films from ‘Sarkar’ to ‘Krrish’ to ‘Lagaan’ and ‘Rang De Basanti.’

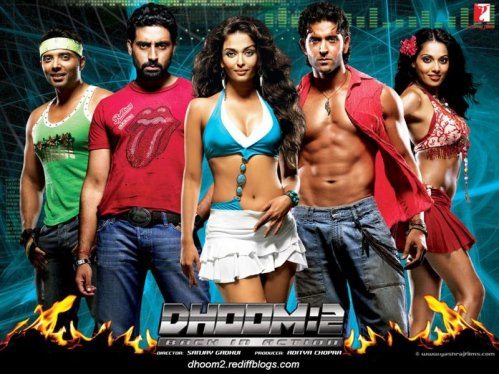

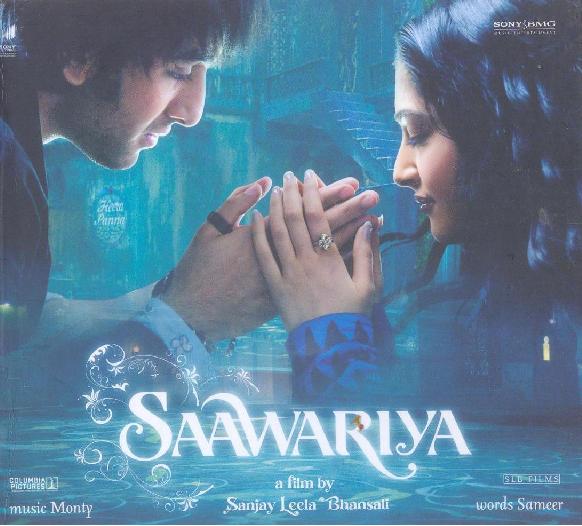

The past year was a virtual showcase of many unusual offerings, each heralding a new trend, including ‘Guru’, ‘Dhoom 2’, ‘Chake De India’, ‘Cheeni Kum’, ‘Chatri Chor’, ‘Gandhi, My Father’, ‘Eklavya’, ‘Metro’, ‘Namaste London’, ‘No Smoking’, ‘Om Shanti Om’, and ‘Saawariya.’

Meheli Sen, who teaches an Introduction to Bollywood Cinema class at Emory University in Atlanta, GA, says, “There is a trend to move away but the basic template of some songs, some action, and some romance is going to be in place. There is a basic grammar of the masala film but there seems to be more focus on different genres since the last ten years.”

Ram Gopal Varma’s ‘Cheeni Kum’, for example, is a move in a new direction, an adult comedy as opposed to the more common immature romances that Bollywood tends to make with younger stars and ensemble casts. ‘Metro’ is another unusual experiment with a narrative that is episodic and not structured. Indeed, Ram Gopal Varma pioneered the style with ‘Darna Mana Hai’. One trend, which has been around for a while, but seems to be gaining momentum is the big, ensemble cast in films such as ‘Eklavya’, ‘Salaam-E-Ishq’ and ‘Om Shanti Om’ where several different star casts and several different stories are woven into one.

Richard Pena, Director of the prestigious Film Society of Lincoln Center in New York, is a follower of Bollywood films and notes the recent changes: “There seems to be more of the spectacle quotient as well as concentration on films with a strong narrative, addressing issues from corruption to crime.”

He adds, “I think some of it has to do with the foreign market for Bollywood films. The South Asian market for Bollywood films abroad, especially with the South Asian communities, has become an extremely important economic factor. Since the audiences abroad are sometimes more tuned to the American style of Hollywood film-making, films are going in that direction.”

While Bollywood films find a large disaporic audience abroad and also a steadily increasing non-south Asian fan base, major Hollywood studios have also realized the potential of the Indian film industry which produces 1041 films annually and is currently worth about US$ 1.8 billion, expected to grow at a CAGR of 16 per cent for the next 5 years to reach US$ 3.8 billion in 2011.

Indeed, the Hindi film industry, which commands a 40 per cent share of the Indian film market, is gaining a global audience. According to the 2006 PricewaterhouseCoopers Global Entertainment and Media Outlook study, the country has over five million home video and DVD subscribers and current penetration levels are expected to grow 31 per cent – a lucrative market to be reached besides the myriads of theaters across he country.

So Hollywood is not unaware of Bollywood’s potential and is ready to invest in the industry. ‘Saawariya’ was the first film made in India by Sony Pictures and several other projects are in the pipeline, such as Walt Disney Studios’ deal with Yash Raj Films to make an animated film and Warner Brothers’ production of Ramesh Sippy’s ‘Made in China’ starring Akshay Kumar.

“There seems to be a growing inter-change between industries,” notes Richard Pena. “ If the films are successful then there will be more investment – if they are not, then probably people will shy away, as they did from the Hong Kong film industry after a certain time.”

Ask Meheli Sen about the ground-breaking movies of this year and she mentions ‘Chak De India’ which besides being a very well crafted film, also was exceptional because it put the faces of ordinary women on the screen which is generally inundated with the faces of the super beautiful: “For me it was a very refreshing change to see different kind of faces portrayed on the screen.”

‘Om Shanti Om’, too, showed how sophisticated the industry has become, making fun of the Indian masala film in an intelligent, very self-reflexive, very self-aware way. The movie was crowded with allusions and references to earlier films, much to the delight of diehard Bollywood fans.

Referring to Farah Khan, who directed ‘Om Shanti Om’ and Faran Akthar of ‘Dil Chatha Hai’, Sen says: “This is a new breed, a new generation of film directors who are very post-modern, who are very playful in their engagement with Hindi cinema – not thrashing it and at the same time it’s not this sacrosanct institution that cannot be questioned or made fun of.”

Bollywood’s embrace of diverse genres has also made it a favorite at the many South Asian film festivals which are taking place from New York to California to Atlanta. At the recent Mahindra-Indo American Arts Council (MIAAC) Film Festival, the program included festival and art houses staples along with the huge Bollywood film ‘Saawariya’ and Rituparno Ghosh’s offbeat film ‘The Last Lear’ which nevertheless starred Bollywood biggies like Amitabh Bachchan and Preity Zinta.

“We showcase independent, Diaspora, art house and alternate films,” says Aroon Shivdasani, director of IAAC. “However, the last few years have seen a dramatic shift in ‘Bollywood films.’ The genre that typically rolled out big band escapist

entertainment and melodrama, has also begun producing socially conscious films like ‘Lage Raho Munnabhai’, ‘Khosla ka Ghosla’ and a host of other films that speak to film- going audiences about real life issues through a lighter lens.”

The birth of the multiplex cinemas in India has also revitalized the Hindi film industry, encouraging the production of off-the-beaten track themes for select audiences, and has seen the middle and upper middle class return to the cinema hall in droves. Says Sen, “Growing up, we used to watch movies with 500 people, a thousand people in huge theaters. So the film had to be made for an audience which transcended class, transcended region, transcended language. That was the all-India film.

Now the all-India film doesn’t have to be made any more because someone can make a film like ‘Omkara’ for the upper middle classes and cut even.”

In India, where audiences for Hindi cinema are in the millions, even a small share of the vast market can mean a box-office hit or at least a movie which floats, instead of sinking. This gives film-makers the impetus for going out on a limb, and trying something very new or bold.

“It’s a question of a new time in the industry and the fact that people are ready to give money to films that are unusual,” says Meheli Sen. “ It finally comes around to that – that a lot of these films are hits or are at least selling – they are getting financed. I think it’s a very interesting time when all these new subjects are being explored.”

Indeed, it is exciting times with experimentation in story-telling, special effects, technology and styling. Looks like the Hindi film industry is coming of age but hopefully it will retain its essential nature, its spunk and its ‘Indian-ness’ even as it explores diverse genres and techniques from across the globe, giving fans a rich feast of cinema to taste and savor. Bolly good!

© Lavina Melwani