Nina Paley’s Sita Sings the Blues

When you see Sita rising from the ocean on a lotus, you are struck by her beauty and the sheer limpid depths of her eyes. Next to her is a whimsical peacock fueled record player, the bird’s beak scratching out the most beautiful music from this to which Sita gently gyrates. The song sung in the honey rich, plaintive voice of Annette Hanshaw, the popular blues singer from the 1920’s, is ‘Mean to Me…’

“Moanin' Low, my sweet man I love him so

though he's mean as can be

He's the kind of man needs a kind of woman like me

a woman like me...

a woman like me...”

Welcome to Nina Paley’s animated film ‘Sita Sings the Blues’, yet another retelling of India’s great epic, Ramayana. Perhaps it would be more accurate to call it, as some have done, ‘Sitayana’ for it tells the tale from the perspective of Sita, not unlike the oral retellings through the ages by village women that made Sita the focus of the story. Only here the story is told through the jazz tradition of torch songs, of a lovely, smoky voiced lament more often heard in a dark New York lounge or bar, than in the rural outposts of India.

This spunky little movie, conjured up on the computer by a single animator artist over the course of five years, ended up making big waves. It’s probably one of the most awarded and most reviewed little films, and has won fans and great praise – and scorn and hate mail.

Watch the film and you are amazed at the lush details, the rich landscapes and literally the cast of thousands – strange demons, the mighty monkey army, the burning city of Lanka and bloody battle scenes all pulled off by a woman named Nina Paley who became producer, director, creator, songwriter and marketer for this whimsical little animated meteor.

The film is like a child’s kaleidoscope – twirl it around and those unmatched, multicolored pieces of glass mutate and form the most amazing, unexpected patterns. Many different influences, emotions and memories – past and present – have gone into this unorthodox retelling of the Ramayana, depending a lot on intuition and serendipity.

Paley is a syndicated comic strip artist (Hots, Fluff), an award winning short film-maker (Storks), a professor at Parsons School of Design, and a 2006 Guggenheim Fellow. Ask her about her witty, slightly irreverent retelling of the Ramayana and she says, “Well, I think really good stories are alive, they are living things. The Ramayana has been alive for 2000-3000 years, maybe even longer. It is a living story, and that’s the trait of really good stories – they live in all these different versions.”

The Ramayana, via Corn Country

So what was the route which brought Paley to the Ramayana? She grew up many miles and light years away from this text, in Urbana, Illinois. The daughter of a math professor, she grew up on the campus of the University of Illinois and recalls, “Even though it’s in the middle of Corn Country, it was in some ways a cosmopolitan, academic town with professors from all over the world, including Asian and South Asian professors.” She even had desi friends as room-mates in college.

The daughter of atheist parents who happened to be Jewish, she didn’t develop an interest in religion till she was in her late teens; in college she took some religious study classes – but religion frightened her initially.

“Why would you believe in some power that could be capricious and malicious – I have enough trouble pleasing my parents and my teachers, why would I want to add to that and need to please God all the time?” she says about that early questioning “ But then I became older, I became interested in my judgments and my fascination increased.”

Paley explored the literature of different religions – “That’s another way of saying myths and that’s not saying they are not true but they are stories with a spiritual component – I feel the stories really talk about being human. I don’t identify with any religion but I do have spiritual experiences and I find myself relating to all kinds of religious stories – not just the Ramayana but also Biblical stories. There’s a lot to relate to.”

Curious and open to all the religions, she still doesn’t want to identify with any one to the exclusion of the others: “I’m not into the dogma part of religion or being in an adversarial relation with others. I’d rather have none and explore all rather than be attached to one, to the exclusion of the others,” she says.

Sita’s Story

Of religious mythologies, she says: “I’m moved by them. I think what the stories are talking about is another layer of reality – I don’t take them literally – I think all religious stories are talking about deeper aspects of humanity.”

So how did this American version of the Ramayana come about? Paley first encountered the epic when she followed her husband, an animator, who had been transferred to Trivandrum, India. While visiting New York for work, she had a cryptic email from her husband telling her not to come back. It was abandonment by email. Devastated, she started seeing parallels between her own life and that of Sita, who was basically abandoned by Rama after she had been abducted by Ravana, the King of Lanka and her ‘purity’ was in question.

During this sad, gloomy time when she could not return to their apartment in San Francisco which had been sublet, she slept on the sofas of friends in New York, and at one such home she encountered the vocals of Annette Hanshaw and identified with them completely. Like the pieces of a puzzle, these sad lamenting lyrics fit in totally with her story – and that of Sita. “I thought it was so obvious I was surprised that no one had combined them together before,” she says.

It was almost cathartic to work at her computer on her own personal Ramayana, and bit by bit it came into being. An earlier, shorter version ‘Trial by Fire’ was shown at festivals and then it took on a life of its own, as she added layers and Annette Hanshaw’s vocals to it.

Ramayana tells the story of Prince Rama, who has been banished to the forests for 14 years due to a boon given to his stepmother by his father King Dussherth. Ever the good son, Rama heads to exile with his loving wife Sita, who insists on accompanying him. When Sita is abducted by the ten-headed Ravana, King of Lanka, Rama battles the evil forces and gets her back. But the relationship is never the same, for doubt has set in, and Rama, ever the Ideal Man, feels he must uphold the morals.

In Paley’s version, the focus is on Sita and is really the story from her perspective. As she writes, “Sita’s story moves from total enmeshment and romantic joy (Here We Are, What Wouldn’t I Do For That Man) to hopeful longing separation (Daddy Won’t You Please Come Home) to reunion (Who’s That Knockin’ At My Door) to romantic rejection (Mean to Me) to reconciliation (If You Want the Rainbow) to further rejection (Moanin’ Low, Am I Blue) to hopeless longing (Lover Come Back to Me,) back to love – this time self-love (I’ve Got a Feelin’ I’m Fallin’).

The film came into being as Paley listened to these songs in her friend’s apartment and feels there could be no film without them because they captured the emotions so well. One wonders what Annette Hanshaw’s reaction would have been to the picturization, and Paley says, “Hanshaw doesn’t have any children but her nephew told me that Annette would have liked it and I was very pleased with that.”

Nina Paley: The Trials of Sita

As times change, perhaps there will be more and more ways of telling ancient stories. Nabaneeta Dev Sen writes in “Lady sings the Blues: When Women retell the Ramayana: “ But there are always alternative ways of using a myth. If patriarchy has used the Sita myth to silence women, the village women have picked up the Sita myth to give themselves a voice. They have found a suitable mask in the myth of Sita, a persona through which they can express themselves, speak of their day-to-day problems, and critique patriarchy in their own fashion.”

These beautiful songs are woven into the movie yet also proved to be ‘a trial by fire’ for Paley. She had poured all her resources into ‘Sita Sings the Blues’, only to learn that releasing it was illegal for though the recordings of the songs were in the public domain, the lyrics were not.

Unable to pay huge amounts to get the license for the lyrics, she decided to resolve the copyright impasse by donating her film to the public. It can be seen and downloaded freely on the Internet, and has shown at countless film festivals, winning many awards.

As Paley states on her website, “I hereby give Sita Sings the Blues to you. Like all culture, it belongs to you already, but I am making it explicit with a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License. Please distribute, copy, share, archive, and show Sita Sings the Blues. From the shared culture it came, and back into the shared culture it goes.”

Her passion for opening ‘Sita Sings the Blues’ to anyone with access to the Internet was because of the Ramayana itself – a story freely shared by all through the centuries. “Imagine if the Ramayana was copyrighted, nobody would be able to share it – there wouldn’t be all those diverse retellings,” she says. “I think the Ramayana aspect of the movie did make me open up more to the idea of freeing up my movie.”

Finally, to ‘decriminalize’ her film, she did go into debt to pay a negotiated fee of $50,000 and almost $20,000 in legal fees for the right to use the songs in the film and market it freely. She says, “Having paid off the licensors, I could have chosen conventional distribution. But I chose a CC BY-SA license to allow the film to reach a much wider audience; to prohibit the copyrighting – “locking up” – of my art; to give back to the greater culture which gave to me; to exploit the power of the audience to promote and distribute more efficiently than a conventional distributor; and to educate about the dangers of copy restrictions, and the beauty and benefits of sharing.”

As the poster child for shared culture, Paley has gained fans and word of mouth has built up the buzz, and speaking engagements as well as revenue sharing, artwork and product sales are in the works.

The Making of Sita Sings the Blues

Paley’s film came about very much by serendipity as she encountered second generation south Asian actors and dancers in New York City, and found the voices in them for her Gods, kings and demons. While Valmiki’s Ram and Sita are consistently good (and hence a trifle boring), Paley’s Ram and Sita are more human and show the mixed emotions of angst and egos – of real humans.

Ravana too is not just the wild ten-headed demon of the Ramlilas – he is shown as a Shiva bhakt who actually pulls out his intestines to play the sitar for the Lord Shiva. Yet a lot of this narration was unplanned and organic as she turned over the studio to three New Yorkers – Manish Acharya, Bhavna and Aseem Chhabra to ramble on their thoughts about the Ramayana, its characters, their halos and their warts. These became the voice of three Indonesian shadow puppets in the film, irreverent and outspoken commentators on the Ramayana, bringing it right into today’s contemporary world.

“We sat in a studio and she threw questions at us in chronological order – who was Dashratha? How many wives? How many sons?” recalls Chhabra. “Our responses, which became a part of the narrative of the film, were completely improvised, unprepared and organic. At some stage we started giving a human face to the characters from the religious text. Then it was Nina who decided how to use our conversations — as a narrative to bind together the 3 different strains of animation.”

Chhabra, who is an entertainment writer, believes the film is unique – funny, creative and overall is respectful of the Ramayana story while viewing the narrative from Sita’s perspective. While ‘Sita Sings the Blues’ has received many awards, it has been through a ton of trouble and also been vilified in some circles. Yet the fact that the film is around, tells us something about Paley’s tenacity and sheer chutzpah.

“Nina truly enjoys controversy and nothing scares her,” he says. “She has gone through so much financial hell making this film. But it is wonderful to see her get recognition and love from the audience and the critics. She is a rare filmmaker who always wants to share the accolades with her cast and crew.”

Sita Sings the Blues: Fan mail and Hate mail

Which brings us to viewer reaction – and of course, there are some who have reacted wildly, without even having seen the film. The movie has been shown in some private settings in India but has not been distributed there yet in any centralized way. It has generated a lot of comments on the Internet including some very abusive comments from the Hindu Right. “You should see the ones I haven’t published,” she says. “They are grotesque!”

Yet the positive comments have outweighed the negative ones. “The Ramayana is complex, dynamic, and relevant to life today, and the film exemplifies this,” one viewer wrote after watching a segment on You-tube. “All Hindus should be happy that it still resonates around the world.”

“Grow up! The world is changing all around you! Your old voice will not be able to continue unless you adapt to new ways of telling old stories!” wrote another.

“In India a holy book, even Ramayana, was never considered to be unchangeable…. in fact almost 200 versions of Ramayana exist all over India, each having a different depiction and even different character assuming the central role…. so no need to be so touchy,” wrote yet another viewer.

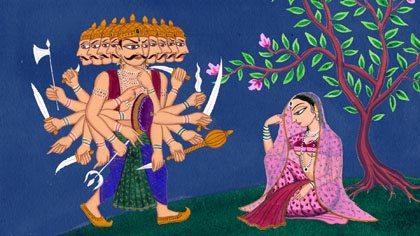

To those who criticize Paley for showing Sita as very curvaceous and scantily clad, she points out that she uses three different forms of animation to depict Sita – including a well covered Indian Mughal miniature-style. She uses the more buxom version during the jazz musical numbers to really highlight her physical beauty. “It makes overt what Sita’s burden was. She is so pure and devoted to Rama and she’s so attractive. It was her beauty which caused Ravana to objectify her and steal her – she was really a pure soul.”

She also points out that many ancient texts, including the Sanskrit Valmiki version of which there is an elaborate English translation online, depicts her physical endowments in great detail. She says, “We consider that depiction of the women degrading to women somehow – showing these aspects of women is considered bad – yet why should a womanly depiction be anything to do with her character?”

Paley says the film does not have any agenda, leave alone a feminist agenda. She does put some harsh words into the mouths of Luv and Kush, about how their father treated their mother. “The Ramayana devotes pages and pages to how righteous he was, that he was a perfect man and the fact that he abandons his wife seems to be no big deal. No matter what Rama does, he is praised.”

One could say it’s a Ramayana for its times. We’ve all seen the image of the mighty Lord Vishnu reclining on the Sesh Naga with Lakshmi massaging his feet. In Nina Paley’s ending, you have Lakshmi reclining on the Sesh Naga with Lord Vishnu massaging her feet!

There is a delicious irony in this and somehow Nina Paley gets the last laugh. For who can argue with this rendition? If God is in all of us, and we are part of the Universe, then aren’t all the parts of the whole a part of the cosmos, of consciousness?

BOX

Nina Paley: A One-Woman Disney

Nina Paley has been a syndicated comic strip artist and award winning short film maker yet in ‘Sita Sings the Blues’ she juxtaposes several different animation styles from ancient Mughal renderings to a hasty, hand-drawn squiggly animation. “I wanted to give a little taste of the different styles of Ramayanas that exist – different times, regions and traditions,” she says, mentioning the different Ramayana art she had seen during her research. “I also wanted to keep myself from being bored!”

While most of the animation is computer generated, the Mughal miniature figures were hand-drawn on parchment paper using antique water colors and were quite time consuming.

Indeed the different styles actually reflect her experience of the Ramayana. “It’s not as if I grew up with one Ramayana,” she says. “I came to the story when I was 34. The first I read was a comic book and since then I have read different Ramayanas and talked to different people about the Ramayana – and no two stories were the same and that just gets reflected in the film.”

(C) Lavina Melwani

(This article first appeared in Hinduism Today)

Related Article: Nina Paley’s New Way of Sharing

(All Photos – Nina Paley)

Have you seen ‘Sita Sings the Blues’? What do you think of it?

9 Comments

Really loved seeing Sita Sings the Blues….nice interpretation..

Manjit

Via Facebook

Great!! 🙂

Thank you all! I’m sure you’ll all agree I had VERY good material to work with!

Via Facebook

Lavina Melwani Rocks!!!!!!!!!!!

Via Facebook

This article is a great way for a “newbie” to begin to get oriented to Nina and all the cool things she’s doing. Thanks! :o)

Via Facebook

Lovely article! I’m impressed.

via Facebook

Fantastic!

via Facebook

Awesome article!

Interesting…..