1090 people reached on Lassi with Lavina FB page – 108 engagements

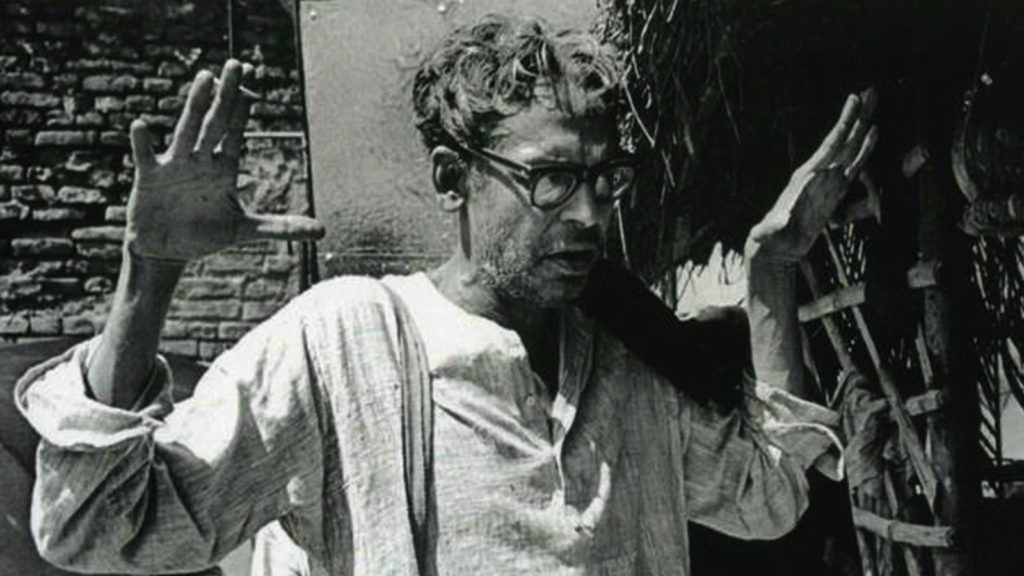

Ritwik Ghatak Comes to New York

Poetry and Partition: A Powerful Retrospective at Lincoln Center

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n the 94th birth anniversary of the iconic Bengali film-maker Ritwik Ghatak, cinema is the gift that keeps on giving. It is the passport for new audiences to enter the past and experience the unique, less-traveled world of Ghatak. The Film Society of Lincoln Center launched the first-ever retrospective of the Bengali master with newly restored works.

[dropcap]G[/dropcap]hatak, who died at 50, was not really well-known to international audiences while he was alive. He completed just 8 films, hampered by finances, ill-health and in later years by alcoholism. A contemporary of Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen, he depicted a changing Bengal, caught in the whirlpool of partition. The angst became a part of his daily life and each of his films carried the pain of partition and of a new nation coming to terms with loss and change.

‘Poetry and Partition: The Films of Ritwik Ghatak’ at the Walter Reade Theatre showed audiences the new restored versions by The National Film Archive of India, and several other organizations, including, in the case of A River Called Titas and Cloud Capped Star, the Film Foundation’s World cinema Project which is founded by Martin Scorsese. According to Gayatri Chakrovorty Spivak, one of the organisers of the retrospective, “This was a chance to see these iconic films in a much clearer version. New York is an important city for film, and the Ghatak Retrospective was long overdue.”

The retrospective was organized by Spivak, Dan Sullivan, Richard Peña, and Moinak Biswas. According to the retrospective notes, “Bengali-born director, poet, and actor Ritwik Ghatak’s career was one of constant struggle—against a public that, per his contemporary Satyajit Ray, “largely ignored” his films; against a society that had lost its way amid rampant modernization; and against a national cinema whose conventions he broke time and again.”

[dropcap]Y[/dropcap]et each of his eight films is lauded as a landmark achievement in the history of Indian cinema, movingly reflecting the social realities of a nation trying to revise its identity in the aftermath of British colonial rule and the partition of India and Pakistan, and representing the melodrama of everyday life under the country’s newly modernized economy.”

The films shown at the retrospective included the Partition Trilogy – The Cloud-Capped Star (Meghe Dakha Tara, 1960), E-Flat (1961), and Subarnarekha (1965) , A River Called Titas (Titash Ekti Nadar Naam -1972), The Runaway (Bari Theke Paliye, ’59), The Pathetic Fallacy (Ajantrik – 1958) and Ghatak’s final, semi-autobiographical film Reason, Argument and Story (Jukti, Takka aar Gappo, 1977).

Each of these films stays with you long after you leave the theater, wondering about loss and partition, the nature of family, human nature and humanity. As Ghatak says in his last film in which he plays the alcoholic intellectual Nilkantha, “I am burning – the universe is burning, everything is burning.”

[dropcap]“R[/dropcap]itwik Ghatak was a powerful filmmaker who gave a passionate representation of the confusion and violence of Partition at the eastern end of India,” says Spivak, who is a professor at Columbia University and literary theorist. She points out that this is particularly important, as the Western partition has received much more attention. His work also gives an account of the Indian People’s Theatre Association, an important movement in the struggle for freedom, from the point of view of a participant.

Spivak along with Moinak Biswas, Professor at Jadavpur University and Surya Parekh, professor at Binghamton University helped organize Global Ritwik Ghatak at Columbia University, bringing together 11 leading international scholars to muse on his films. It included Kenyan activist intellectual Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Swedish investigative journalist and cultural theorist Stefan Jonsson, and film theorists Nora Alter and Dudley Andrew.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]s Parekh says, “The magnificent restorations, involving, among others, the National Film Archive of India and Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, give us an entirely new experience of watching these films, especially Runaway. We felt that a retrospective in New York at Lincoln Center would introduce a new generation of viewers to the work of one of India’s greatest filmmakers.”

He adds: “For me, Ritwik Ghatak’s films teach us to imagine the complexity of historical events. They do so through a masterful cinematography and intricate use of sound. Ghatak’s trailblazing films ask us to move from our specific contexts into global concerns.”

Ghatak once said in an interview that art was not a trivial thing. “The primary objective of making films is to do good to mankind. If you do not do good to humanity, no art is a true work of art.”

I was watching his films for the first time but I could identify with what Jacob Levich wrote about his work in ‘Subcontinental Divide’, a 1997 Film Comment profile of Ghatak: “Viewing Ghatak is an edgy, intimate experience, an engagement with a brilliantly erratic intelligence in an atmosphere of inquiry, experimentation, and disconcerting honesty. The feeling can be invigorating but never comfortable.”

I found it hard to put some of the films out of my mind. With ‘Cloud-Capped Star’, one feels an almost personal sense of grief, of despair. That one can continue to think about the movie weeks after seeing it is a testament to its power.

As Shiv Kotecha in Frieze wrote, these films are not cathartic and speak to the enduring violence caused by forced exile: “These films rattle with and against their subjects, pulping atrocity to find the agonized pith within. Ghatak’s singular filmic vision depicts the implacable, everyday groping toward hope, if not a home, that can and will encumber a life lived in exile.”

Spivak and Parekh, along with other organizers of Global Ghatak believe that Global South cinema should be integrated into all discussions of global cinema and project a vision of feminism and democracy. There are plans for a book evolving from the papers presented at the symposium. Though international scholarly publications of this sort typically take a long time, the participants hope that the contribution to teaching will be immediate.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]sked about the legacy of Ghatak’s work, Spivak said, “His lasting legacy seems to me to be an acknowledgment of the common people, an acknowledgment of the rural as well as the urban, and a still unusual focus on the intellectual and social power of women.”

She also emphasized that all of his films, but especially Subarnarekha, are a powerful intervention against caste-discrimination. “His work is also animated by a spirit of co-existence between Muslims, Christians (Ajantrik), tribals, and Hindus.”

Ghatak was very aware of the fact that change is the only constant, even as he grieved for the partition of Bengal into two different countries, of lost rivers, lost childhoods. He mused, “Civilization never dies. It may change, but it is eternal. Where the paddy field is born on the dry river bed of Titash, there begins another civilization.”

Ghatak’s films are frenetic, heartfelt and heartbreaking, as agonized and without any final answers as life and existence itself. Yet with their tales of partition and loss, of refugees and homelessness, of changing families, of pain and ultimately hope, they touch a chord within contemporary audiences and are relevant even – perhaps especially – now.

(This was first published in my weekly column India in America in CNBCTV18.com)

Related Articles:

Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy – A Rebirth