7002 people reached on Lassi with Lavina

Nita Anand, Saumya Arya Haas, Poonam Sharma and 6 others like this. Shahana Sen, Deborah Snyder and 4 others like this on Lassi with Lavina FB page

1123 views on LinkedIn – 24 Likes

Google + – 19 + on India Group

Celebrating Indian Women:

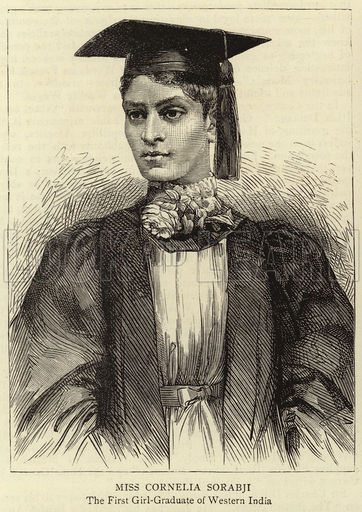

Cornelia Sorabji – India’s First Woman Lawyer

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]oday we have thousands of Indian women lawyers, both in India and the Diaspora. But how lonely and frustrating must it have been to be the first and to try and change society?

We pay tribute to the one who started it all, and won the right for women to stand up in court and argue a case. Her older sisters were not permitted to go to university simply because no woman had ever been admitted. When Cornelia Sorabji managed to accomplish this feat, she found male students slamming the lecture doors on her face because they did not want to give up their domain.

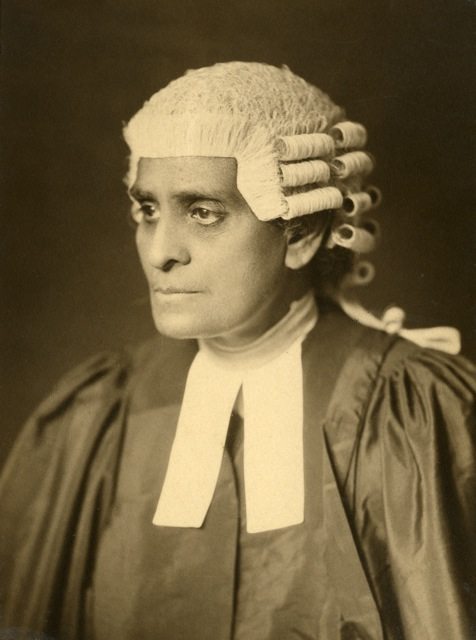

In England, she was refused a scholarship simply because she was a woman, was not allowed to read in the Lincoln Library and had the hardest time sitting for the barrister’s examination. Yet her sheer determination and spunk saw her through and she went on to become the first female lawyer not only in India but also in England.

[dropcap]C[/dropcap]ornelia Sorabji, born in 1866, was India’s very first woman lawyer. She was the first female graduate from Bombay University admitted to Allahabad High Court, and went on to become the first woman – Indian or British – to read law at Oxford University and also the first Indian national – male or female – to study at a British University. She was the first woman to practice law in both India and Britain. In fact, she had to get special permission by Congressional Decree to take the Bachelor of Civil Laws exam at Somerville College, Oxford.

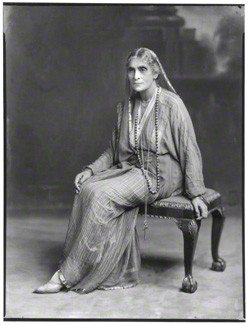

Sorabhji was very much a part of colonial times and yet transcended the Victorian mindset by always standing up for women, especially the secluded and the vulnerable. In those days women in India had a very secluded life and she took up the cause of the purdahnashins – women who in spite of having great property, did not have the power to safeguard their own interest. In spite of passing the LLB examination of Bombay University in 1897 and also the pleader’s examination of Allahabad High Court two years after that, she was not recognized as a barrister until 1924, when the laws barring women from practicing underwent a change.

Appointed a Lady Assistant to the Court of Wards in 1907 and later in several other provinces, she managed to fight for the cause of women in purdah and of minor children, working on bringing social change in their lives. She has written several books which document her commitment to women and children, including Sun-Babies: Studies in the child life of India and Between the Twilights : Being studies of India women by one of themselves. She helped many women change their lives around, helping them fight legal battles in a patriarchal society which saw no value in them without a male protector.

In 1924, the legal profession was opened to women in India, and Sorabji began practicing in Calcutta. She retired in 1929 and lived in England, while frequenting India, till her death in 1954.

Far from her homeland of India, she is being remembered in Britain with a new artwork titled The Jurors, which has been created by the artist Hew Locke for Runnymede, Surrey, UK to mark the 800th anniversary of the sealing of Magna Carta. It has been installed at Runnymede meadows, the site where Magna Carta was sealed, at a meeting between King John and 25 barons on 15th June 1215.

It has been commissioned by Surrey County Council and National Trust, and features 12 chairs, each honoring a noted figure. Here is a description of the work: “Twelve intricately worked bronze chairs stand together on this ancient meadow. Each chair incorporates symbols and imagery representing concepts of law and key moments in the struggle for freedom, rule of law and equal rights. The Jurors is not a memorial, but rather an artwork that aims to examine the changing and ongoing significance and influences of Magna Carta.”

Cornelia Sorabji is one of the inspirations behind this work, because “She worked with many Hindu women in purdah, who were not permitted to meet men in public or defend themselves in court.” Hew depicts Sorabji standing in front of a courthouse and surrounded by decoration from a purdah screen, used to separate men from woman indoors.” More details at artatrunnymede.com/magna-

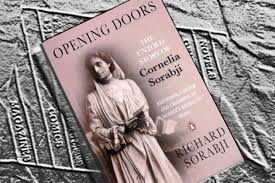

Cornelia Sorabji’s nephew, Sir Richard Sorabji, has written a biography of her life, ‘Opening Doors.’ and also delivered a lecture at Gresham College – Opening Doors: The Untold Story of Cornelia Sorabji – Reformer, Lawyer and Champion of Women’s Rights in India . Sorabji is a historian of philosophy, mostly Western, but with an interest in Indian and Islamic. He is an honorary fellow of Wolfson College, Oxford.

Here are excerpts from that talk. In this fascinating piece you see that Cornelia Sorabji actually met and was befriended by names from history like Florence Nightingale and Lord Alfred Tennsyon. An amazing life and a very inspirational one.

Opening Doors with Cornelia Sorabji

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]t is a story of a life of cliff-hangers. She never knew whether it was going to be triumph or failure next, and indeed, this continued for the whole of her life. This story of cliff-hangers is set against the background of huge movements which were going on in India. I am not pretending to be a historian who can explain what was going on in India, but I have to be conscious of the background all the time.

My grandmother was a Hindu but had been brought up by Christian missionaries because her mother died very shortly after her birth. She married my grandfather and they moved to Pune and, by great chance, I went with my daughter, also called Cornelia, 16 months ago, and we found the family home, with all the original furniture. There was the grandfather clock of which there is a picture in the book. There was the grand piano and all the same pictures on the walls. There were the beds they all slept in. There was the family carriage, for a horse of course. It remained intact because it was sold 100 years ago, to a hotel, which had two careful owners who thought that this was the furniture that would attract guests, so they kept it.

My Grandmother founded four schools. The two big ones were actually in the house, or rather, they built over the garden, and they are still there. When they first started in 1876, there was room in the house to have just a few children, but they had to cover every inch of the garden before they had finished. They then had to build two schools elsewhere: one school was a free school, for very poor Hindus, with Marathi as the language; another was an Urdu-speaking school, for poor Muslims; and then the main school was English-speaking, mostly for Zoroastrians; and then there was an infant school, again, mostly for Zoroastrians, who had not yet learnt English, but they would have to learn English if they wanted to be successful. She was a very strong character, very proud of having so many daughters – seven daughters to one son, my father – and very much outgoing to all communities, absolutely regardless of race or religion.

A Woman in a Man’s Place

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]y grandfather pressed very hard to get his two oldest daughters into Bombay University, but they were refused on the grounds that no woman had ever been to university. However, with Cornelia, he finally succeeded in having her admitted and she matriculated at the age of 16. Six years later, she came out top of her college in English Literature. Her college was in Pune, which was a branch of Bombay University, one of the only four first class degrees of that year. She managed this despite most of the boys slamming the lecture doors in her face, trying to prevent her going to lectures. They were so unused to a woman that they simply did not know how to handle it.

Having done so extremely well, she had very good reason to think she might get a scholarship to come to England and continue her studies. The scholarship was refused on the sole ground that she was a woman, and a question was raised in the House of Commons, by an old man with a beard. This was Sir John Kennaway, who had an enormous beard, and it is thought that he inspired Edward Lear’s poem “There was an old man with a beard”. He asked the question of whether a woman had been refused in the British Empire a scholarship to an English university, on the grounds that she was a woman. The Secretary of State for India said the answer was yes but, meanwhile, some ladies, including Florence Nightingale, got together the money anyhow, out of their own pockets, to create a scholarship for her to come to Oxford.

Celebrities and Oxford

In order to raise the scholarship, they had her photograph in the Queen, which was certainly one of the society magazines, and had been the society magazine, with a description of her, and so, when she arrived, as a young student from a remote town in India she thought nobody would ever have heard of her but she was actually a celebrity. She thought people were pulling her leg when she arrived in Somerville College Oxford which was only 10 years old, and said, “Now, we’ve asked senior people in Oxford to come and meet you.” She was very used to being teased and she assumed this was a continuation of that. Actually, some of the most distinguished people in Oxford wanted to meet this celebrity.

However, she was told that, nonetheless, as she was a woman, she could only read English Literature. Law was not an option open to women. However, in the first term, the most influential academic in the country, a very close friend of Gladstone, was the philosopher Benjamin Jowett. He called into Somerville especially to see her, and he invited her, with Miss Maitland as chaperone, to the concerts of which he was so proud, because he had founded the Balliol concerts that are going on to this day.

He had actually given Balliol College a second organ. There was an organ in the chapel, obviously, but he had paid for a second organ, in the dining hall, so that there could be first class concerts. He started bringing her, on his arm, or, later, he on her arm, to those concerts, about five times a term, as his special guest, having first introduced her to the leading figures of Victorian society. At one point, he sent her to meet Florence Nightingale, who was one of her benefactors.

Tennyson’s Last Poem

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]t another point, he sent Cornelia and my father to see Tennyson, in his last days. Tennyson had just written his last poem, not published it, and under oath of secrecy, he read them his last poem about Akbar the Great and he wanted two young Indians to advise him about whether he had made any mistakes. Very shortly afterwards, Cornelia was asked to the very moving funeral service for Tennyson in Westminster Abbey, in which “Crossing the Bar” was read, which was about the soul going out into the next life.

Not only did Jowett help her in that way, but he arranged that she could read Law, and he had a special Law course devised for her. Eventually, he arranged that she could sit the examination for the degree of Bachelor of Civil Law which is a postgraduate degree, very difficult to get, and she tried to do this in two years. Usually, it was done by people who had already become barristers in London as well as doing a degree, and had had at least five years training.

The Law is Not for Women

[dropcap]J[/dropcap]ust before the exam one of the examiners refused to examine her. So Benjamin Jowett, who was the most senior person at Oxford, called together Oxford’s University Council, to debate the motion that Oxford University should accept Cornelia Sorabji, and it was passed. So, the night before, she knew she could sit the examination. However, the examiner who had refused to examine her was absolutely beastly and we have a letter in which she describes how beastly he was. Cornelia turned round at the end and damned his book as ‘something that some people say but it is wrong’. He gave her a much lower class than she had hoped for – a third, and she was absolutely devastated. Even so, she had passed although no woman could collect the degree for another 30 years.

Cornelia had a year in London with a solicitors firm, Lee & Pemberton in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Lord Hophouse, the husband of one of the aristocratic women who had organised the scholarship for her, took her and got her allowed to read in the Library in Lincoln’s Inn. I imagine she must have been the first woman allowed to read in the Lincoln’s Inn Library.

Therefore, while in England she had practiced in a solicitors’ office and had passed the Bachelors of Law. When she went back to India, she hoped to do good for women as a barrister. However, when she went back in 1894, the Chief Justice in Bombay told the solicitors not to employ a woman, so the job that she had been offered as a solicitor was rejected.

A Barrister for the Maharajas

After that, she thought that she would do better if she took the undergraduate degree in Law at Bombay. After all, she had a postgraduate degree from Oxford, so she sat the undergraduate degree in Bombay, and they failed her. She then found that, although the British were not prepared to have a woman as a lawyer in Bombay, the Maharajas were more than happy, so she spent the best part of five years attempting indeed to be a barrister and working for Maharajas. However, she found it unsatisfactory, not because the Maharajas were not friendly and perfectly willing to help a woman, but because they gave her only frivolous cases.

The Elephant’s Lawyer

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he most frivolous case was when she was asked to defend an elephant against somebody who had removed its banana grove. So there she appeared, in the palace, by six white horses with outriders and drawn swords and found that the culprit who had taken the groves was the Maharaja himself. Then it turned out that the judge was also the Maharaja! He said that he was sitting on a swing, and he was playing with a gramophone beside him, ‘Champagne Charlie is my Name’, was the tune, and he said, ‘Your case is won.’ She replied, as a young woman, ‘I do not want my case to be won – you have not heard it! I’m going to give you my case!’ He said, ‘Well, give it if you like, but this case is won.’

So, she delivered her speech, and was ushered out by the Prime Minister, and she said, ‘What’s going on?’ The Prime Minister replied that, ‘Well, his Highness decided a long time ago that he would never understand the law, so he has a very simple rule: if the dog likes the lawyer, the case is won; if the dog does not like the lawyer, the case is lost.’ The dog had licked Cornelia when she arrived and she felt this was frivolous. She was an ambitious young woman and she hated these practices.

Also, it was very difficult in the princely states, where the Maharajas ruled, with only a British veto on what they did. A third of India was governed by the Princes, not directly by the British. She found that, in these princely states, it was very difficult to get evidence to support women, because males just would not speak. It was only in British-run India that the British had enough power to compel men to give evidence, and so she found that she was not able to help women. Therefore, she tried setting up a brother and sister team in Allahabad, which soon became the center of Indian law.

‘Oh, we didn’t mean those foreign languages – we meant these foreign languages!’

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]here were other big legal centres, like Bombay, but Allahabad became the centre of the great future nationalist, Motilal Nehru, the father of the Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. She hoped that she could help my father prepare cases and would eventually be allowed to be a barrister, and they agreed providing she learnt these foreign languages. Well, she learnt the foreign languages and passed quite easily, and then they said, ‘Oh, we didn’t mean those foreign languages – we meant these foreign languages!’ So she learnt those and passed those, and then they said, ‘Oh, well, we did not actually mean any foreign languages at all.’

This was in 1899, and she had spent five years trying to become a barrister. She decided that this was not the way forward, so she spent the next five years devising a role. She thought that she should become a legal advisor to the British Government on the state of secluded women, who could never see a lawyer because all lawyers were men. These secluded women, who were suffering, needed a female because they could never be interviewed so long as all lawyers were male.

Child Brides & the Outside World

These were women who were child brides. They were married off, occasionally in infancy, but very commonly at four, certainly by eight, and, with a lot of warnings by 11. Once they had been married off, a lot of them never saw the outside world again. They certainly could not speak to any male other than their husband. If they were widowed, they could not speak to any male at all. Their education stopped when they were married, so naturally, they knew nothing about the law – they had no education whatever. However, they were a very wealthy class of women, and they were guardians, if they were widowed, of huge estates stretching hundreds of square miles for their male heirs. They also had rights, above those of any English women at the time, to use the property so long as the heirs were alive. Nothing could be kept for after their death, but they could use the property while the heirs were alive.

So, naturally, these women, who might be widows by thirteen – some of them of course were older widows, but some of them were only 13, they were pretty defenceless. They could not see any lawyers and people were trying to get their estates. People were trying to get their money by fraud, about which they knew nothing, or by murder of the children, and this was very common.

Then, in 1904, the final thing happened. The head of Merton College, Oxford, had always asked Cornelia to dinner to entertain his lawyer friends from the City, because she was very good company. His brother, who was then called Lord Broderick, was appointed Secretary of State for India, the one person who was superior to the Viceroy. He overrode Lord Curzon, and said he wanted a woman appointed as advisor to women who were secluded. Curzon had refused twice, indirectly, through his aides, to consider the matter.

Adviser to the Secluded Women, In a Palanquin

So, in 1904, she went out, and she was interviewed in Bengal, and given a large part of North-East India to be legal advisor – sometimes called advisor to the British, sometimes called advisor to the secluded women. It was tremendous trouble: five years trying to be a barrister, five years trying to get this post of legal advisor, and now she had succeeded, and it was a stunning success for 18 years, not without some opposition, but it was the most successful part of her life.

These women, who were widows, all believed that it was their fault that they were widows – they must have done something in a previous incarnation which had brought about their husband’s death – if they were Hindus. Funnily, their husbands did not think that they had done something in a previous incarnation to bring about their own death – that had not occurred to them! I find this interesting, as a philosopher, actually, because a lot of philosophers are at work trying to find moral principles that would be accepted by any rational being, but I think if any philosopher read about these women, they would give up the effort, because these women were absolutely rational but it would be no good walking in and telling them, ‘Wait a moment, it maybe was not your fault – it might have been your husband’s.’ They just would not believe that. It is not true that there are moral principles that will appeal to every human being. I am afraid my philosopher colleagues and I are probably wasting our time!

For the next 18 years my aunt was carried to these fabulous palaces on a palanquin through the middle of the jungle. A palanquin is a fairly uncomfortable mode of travel because it exercises every joint in your body because the person is bobbed up and down the whole time, and they keep landing. She actually rather enjoyed these travels, and she did not merely protect the women against fraud or attempted murder. She produced reconciliations, which were much less expensive, so that people stopped quarrelling and came to her to have the disputes solved at much less cost and much more quickly. She was partly persuading the British that one or two of them were educated or clever enough to run their own estates. She looked after health, which was a major problem. Obviously, being a child bride and being pregnant at 10 or 11, was a major problem, but the children were often sickly too. She appointed tutors, both for the girls and for the boys, so that the next generation of women would be educated and understand the law, and so that the boys would know how to run their estates. They had not learned agriculture, and yet, they were responsible for hundreds of acres of land.

Cornelia’s Purdah Parties

She also had Purdah parties. Eventually, she persuaded the shops to hold Purdah days when secluded women could come and go shopping. Purdah parties were parties for these secluded women. The Purdah is a curtain – they were not just behind a little veil, they were behind a curtain. She had parties, in which even the entrance to her house was secluded, and she persuaded the Viceroys to follow this custom of having secluded parties at which no male could even see who was arriving.

Education before Legislation

One important principle she had was that it was no good, with a couple of exceptions, legislating for the improvement of women’s rights unless the women had been educated and thought themselves that this was right. Therefore, one of her slogans, even from student day which featured in her very first publication while she was a student at Oxford, was ‘Education before legislation’. She made two exceptions: one was Sati, the practice of Hindu widows being burnt on their husband’s funeral pyre, which was banned by the British in the 1820s, but she had a case of a ward of hers successfully committing Sati in 1921. She took that as a sign that actually legislation can be ignored, even 100 years later. The other exception was child marriage. She thought it was quite good to have legislation first. However, in both cases, she legislated merely to set an ideal, not with the expectation that the law would be obeyed immediately – it would take generations for it to be obeyed, because, in her view, the education had to be done first.

She had a very unusual view on education, which I think would be very helpful in some circumstances now. She had the view that children should be educated against custom; they should be educated by using custom to modify custom.

Home and the World

[dropcap]P[/dropcap]erhaps the greatest thing she did for her secluded women was this. Most of these women had never been out of their house since they married. She first, during her main career, got permission for six to be trained as nurses, still in secluded conditions, but that was a huge change, because they never thought about anybody outside their own family. They never saw anybody outside their own family from the age of four, eight or 11. Now, these were people thinking about nursing all sorts of kinds of people, quite different from their own family, and actually going out of the house to have a trade in a public place, where they had never been before.

The most remarkable thing was in retirement when she actually got some of these women to go out to towns and villages, meeting a class of woman they had never seen – these were very wealthy women – and social workers telling them about how to look after infants, how to take care of pregnancy and so on, giving them gifts for maternity situations, and so on. She got the women themselves to go out into an environment they had never seen before to help other people.

Well, that was her main career, working for these women in remote, but lavish, palaces, with very secluded horizons.

When she had finished her main career she came back to London. 1922 was the first year that Oxford women were allowed to collect their degrees, and the first year women were called to the Bar. She was still working in India in 1922, but she came back to London and in 1923, she was called to the Bar in England, collected her degree from Oxford, and thought she could help women as a barrister.

She was appointed to a lofty rank in the so-called Indian Civil Service, which was in effect the British Civil Service, with just a few Indians in it. However, it was a very elite Service. She had a pretty good time because the people who appointed her were very good to her, and supportive, and very grateful actually, because she saved them an enormous amount of trouble by getting these reconciliations, solving these problems and stopping these murders.

Indian or English, Too Brown or Too Anglicized?

It is unclear as to whether she saw herself as English or Indian? She oscillated rapidly. Sometimes she thought ‘I am wholly English,’ with justification. Everybody wanted her in the Oxford or London circles. Sometimes she thought ‘I am only Indian’. Often she thought, ‘I am neither – I am rejected by both sides.’

She did not fit any label. It cannot be said that she was a colonialist because her employment was from the colonial regime. She stood up to the colonialists whenever she thought they were wronging her secluded women. She was not a feminist exactly at all. If she had been a feminist, she probably would have tried to ban Purdah, which was the normal view of advanced, progressive women. She was not a typical feminist. However, I think she is quite a role model for people, because she did not come from a dominant group. She was not from a royal family; she was not from the governing family; and she was not English. She did not actually belong to any group. Due to the conversion to Christianity of her parents, she did not belong to any identifiable group. She was too brown, but she was too Christian, she was too anglicized with perfect English and perfect English manners. She did not belong to any group, so she might have been at a great disadvantage, but she got what she wanted and she did something for these women, by sheer determination.

(Excerpts used with permission from Professor Sir Richard Sorabji)

Do you have success stories to share? Please do!

Related Article:

Raising the Bar – Indian Women in the US Legal System

18 Comments

Thank you Asra – will share your comment with the readers of Lassi with Lavina

Asra Nomani via LinkedIn

What a lovely part of our history in India. Thank you for sharing.

Preeta Bansal, I think she would have been very proud of you – you have certainly followed in her footsteps!

Preeta Bansal via Facebook

Thank you for writing about her! I’ve been fascinated by her untold tale ever since I saw a fleeting reference to her in London a few years ago, and have been researching her untold story for a bit. Great to see this!

Well, if you read what she had to go through, it was extremely frustrating! Her nephew Richard Sorbji wrote ‘Opening Doors’ -a book about her adventures and many anecdotes are in my piece. It will just blow your mind – the way females were treated in an all-male world.

Roshni Babu via Facebook

Why only lonely and frustrating?? It could have been very empowering and exciting too, right ???

HJ Patel – I truly agree with your one-word description!

H J Patel via Facebook

Wow!

Glad you enjoyed it – it is a truly inspiring story.

Rakesh Prabhakar via Facebook

India’s First Woman Lawyer born in 1866… an interesting read!! Thank you for sharing!

via Google + Three likes and three shares

Kavita Gugnani +1’d

Nungavaram Ramamurthy reshared and commented

Bharat Tripathi reshared

Firoz Khan +1’d

Binu Mehta +1’d and reshared

+Nungavaram Ramamurthy

Congratulations – you must be so proud of her! Perhaps she can share this story with her students.

Via Google + Nungavaram Ramamurthy

Wow! My daughter is a Harvard educated lawyer now Law Prof at Suffolk U in Boston. She will be happy to read this.

Chandni Dayal on Facebook

Nice Share

221 views on Linkedin and 3 Likes

On Twitter – Tisca Chopra @tiscatime

What an amazing life! Thanks for sharing @lavinamelwani ..

8 Likes

Google +

Bharat Tripathi reshared

Firoz Khan +1’d

Binu Mehta +1’d and reshared

11 + on Google Incredible India community

Navin Dubey +1’d

Mahendra Chauhan +1’d

Mahavir Mudkanna +1’d

manvi mittal +1’d

kanika Mittal +1’d

Ridhi Rajput +1’d

Uma Pm +1’d

Rajeshree Kundu +1’d

dharmendra sharma +1’d

Subhashree Bhuyan +1’d

Ravishankar Nirala +1’d

Comments via Pranay Gupte’s Word People Awards on FB

Suvir Saran, Tanuja Desai Hidier, Jay Mandal and 3 others like this.

Roy Wadia – Salute.

Shrimati Lal – She deserves full credit. I just wish the legal ‘system’ was cleaner and more efficient (and less corrupt!) Thanks Lavina Melwani.

Sunitaa Shashank Very revolutionary. Thank you Ma’am Sorabji

Lavina Melwani So glad you enjoyed this inspiring story – will share your comments with my readers on Lassi with Lavina.