India’s Freedom at Midnight – Sixty Years later.

This piece was written in 2007. Now it’s a decade later – India’s 70th anniversary of Independence…

How do Indian-Americans connect to this momentous event?

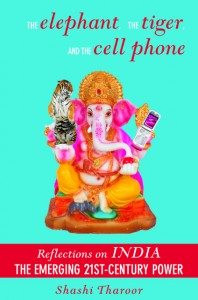

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]magine this: Lord Ganesha, beaming benignly, with a fierce tiger perched on one hand – and a cell phone in the other! This is the photograph on the cover of Shashi Tharoor’s new book, “The Elephant, The Tiger and The Cell Phone: Reflections on India, The Emerging 21st Century Power.”

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]magine this: Lord Ganesha, beaming benignly, with a fierce tiger perched on one hand – and a cell phone in the other! This is the photograph on the cover of Shashi Tharoor’s new book, “The Elephant, The Tiger and The Cell Phone: Reflections on India, The Emerging 21st Century Power.”

An apt image of India in its 60th year of independence – roaring and rearing to go, a technical and economic juggernaut, but always anchored to its cultural and social underpinnings.

Born out of partition and bloodshed in 1947, India celebrates 60 years of struggle and survival, and finally success. “Indian nationalism is the nationalism of an idea, the idea of an ever ever land – emerging from an ancient civilization, united by a shared history, sustained by a pluralist democracy,” writes Tharoor. “India’s democracy imposes no narrow conformities on its citizens.” As he points out, “The whole point of Indianness is its pluralism: you can be many things and one thing. You can be a good Muslim, a good Keralite, and a good Indian all at once.”

Which makes one wonder, can one also be a good Indian – and a good American at the same time? Can one live continents away physically and still wake up, in the mind’s eye, in a homeland where the skies are thick with crows, crowds swarm the streets and the vendors call out their wares in familiar neighborhoods?

Can changed passports and altered surroundings still make one’s heart fill with joy and pride at the 60th anniversary of a nation one has physically left?

Madhulika Khandelwal, Director, Asian American Center at Queens College, believes that this anniversary has great meaning for immigrants for India is still the home country, even though some of them may have become American citizens. She points out that India is changing – and so is the Indian immigrant population in America.

“The immigrants of today and the immigrants of the last decade will have a different take on India than maybe the immigrants of 40 years ago,” she says. “I think it will continue to be important for immigrants but how do we assess the relationship that the next generation will have with India and what that means?”

An Immigrant Remembers…

Asad ur Rahman of Brooklyn, NY, is one such immigrant whose story – and that of his children – is still interlinked with that of India, even though he immigrated 40 years ago. As a boy growing up in the small town of Dathhraon in Moradabad, he was swept up into the freedom struggle since his father and uncle were both active participants. He remembers the 250 year old family house and the khadi his father and uncles always wore. “Gandhiji, Maulana Azad and Jawaharlal Nehru came to our town,” he recalls. “My uncle was involved in the underground resistance and my cousin and I would put up nationalistic posters secretly. So I grew up with that consciousness.”

Asad ur Rahman of Brooklyn, NY, is one such immigrant whose story – and that of his children – is still interlinked with that of India, even though he immigrated 40 years ago. As a boy growing up in the small town of Dathhraon in Moradabad, he was swept up into the freedom struggle since his father and uncle were both active participants. He remembers the 250 year old family house and the khadi his father and uncles always wore. “Gandhiji, Maulana Azad and Jawaharlal Nehru came to our town,” he recalls. “My uncle was involved in the underground resistance and my cousin and I would put up nationalistic posters secretly. So I grew up with that consciousness.”

While in high school, he even had a brief meeting with Gandhiji who was visiting the Bhangi Colony, next to the Birla Temple. A neighbor had asked him to pick up a book for Gandhiji. “I went on my bike as fast as I could,” he recalls. He was rewarded with a gracious smile from Bapuji on his return.

As a student at St. Stephens College, he got swept in the trauma of the riots of September 1947: “A part of Delhi was burning and there were not only fires but machine guns and grenades bursting and the college was isolated. I remember being taken in a military truck to the Old Fort which had been turned into a refugee camp – it was night and there was absolutely no light. It was a very chaotic situation – there were refugees streaming in nonstop. There was only one tap of water for hundreds of people. Our house was attacked and there were fires raging for three days. It was a very difficult time, with riots all over the country.”

After independence, Rahman, who is a professor of English, went to Cambridge and later to the US where he taught at the Brooklyn College of The City University of New York, along with his late wife who was also an academic. Rahman has lived here since the 60’s but he India is still central to his identity. He feels the pull of India but like most immigrants, his life and family are here.

The ongoing connection with India has led him to take yearly trips and he stays there for four months at a time. He finds tremendous changes, with good roads and signs of prosperity everywhere – where there used to be mud and thatched huts he sees brick houses: “The present government has done a good job but it’s a big job and will take a long time.”

Does he feel in this 60th year of independence that Muslims have made strides in India? He believes so and has his hopes in the younger generation: “They have a different frame of mind and are confident that if they work hard, prejudice or no prejudice, there is no question they will succeed. Muslims are now beginning to establish schools and colleges all over the country, even for women.”

A Daughter’s Perspective…

His daughter, Zeyba Rahman, was only 13 when she came to the US, via England, and she has a different relationship with the home country. Today a well-known cultural entrepreneur and chairwoman of the World Music Institute, she spent all her growing years in New York. She has seen the community grow and expand.

“At the time we came there wasn’t really a community,” she recalls. “There were a handful of people from the sub-continent. My father, who with his family was a part of the freedom movement, had told us stories about it. He was very aware that this was a very special day and even when we were growing up in New York, my parents made a point of marking the day and talking about the developments that were taking place in India. We were very conscious of August 15 and January 26.”

Growing up, surrounded by America, did she ever feel did conflicted?

“Because of the way my parents had raised us, I felt no conflict,” she says. “I felt very much Indian and very proud of being Indian and even as we became a part of the fabric of America, our cultural and national identity was very secure. My parents were both English literature professors but when we came home they had a rule that we spoke Hindustani so the language was kept alive.

They took us to cultural performances and so we kept our connections to India very much intact. Once there was a community in the late 70’s, my father started to have mushairas or poetry gatherings and other cultural activities.”

The Pull of India …

This brings us to the intriguing question of the bonds – or lack of them – between India and children of immigrant parents born in America. Do they feel the same pull which their parents feel? Khandelwal believes that the immediacy might not be there for this generation will lack the historic perspective that immigrants may have. An immigrant herself, she observes, “My basic or fundamental identity is Indian – I can’t separate it from me, even though the more years I live here, the longer I live here, it’s the American part of me that grows. The Indian part of me is such a basic of my identity that I cannot throw it out of my system. That I cannot change – and I don’t want to change it.”

Maybe there’s not that much flag waving here, and August 15 is certainly not a national holiday in the US. Even the India Day Parade has to be on a designated Sunday. Yet it still is an important day for Indians in the Diaspora. Says Khandelwal, “It’s a time to think of what India stands for as a nation. Almost every ethnic group in America has shaped its relationship with the home country over generations and worked out what it means to be Italian-American or Greek-American. In that way, young Indian-Americans are shaping their own relationship with the home country, and while they may be distanced from the immediate emotions, their relationship is getting stronger all the time.”

She points out that the relationship is shaped in many ways – through their parents and the older generation, through the media and even from mainstream perceptions of India. Indian independence means so many different things to different people and India is on the radar of everyone from economists to style gurus to ordinary people.

Bollywood, also a flashy shorthand for India, has fans everywhere, people from the Caribbean to other South Asians, and even the larger American population. A sense of India is filtered through the parades, the film star grand marshals, even the wax replica of Aishwarya Rai at Madame Tussand’s.

“Indian independence, which is of immediate significance to Indians, then begins to cross these ethnic and national boundaries,” says Khandelwal. “It’s also a part of American multiculturalism – we need to tell others of how important India is and what it represents for us and for them too. The observation of and significance of Indian independence is no longer limited to Indians alone. We want to communicate to other people how important it is.”

That brings us back to Shashi Tharoor, one of the eloquent communicators of what India stands for. Tharoor, who was the Under-Secretary of the UN in a long and distinguished career, has seen India and its impact on the world from many vantage points. He is also the author of India: From Midnight to the Millennium and Beyond, a thought-provoking book which even President Clinton has read. Interestingly, Tharoor is an Indian national who has probably lived outside of India longer than most immigrants!

That brings us back to Shashi Tharoor, one of the eloquent communicators of what India stands for. Tharoor, who was the Under-Secretary of the UN in a long and distinguished career, has seen India and its impact on the world from many vantage points. He is also the author of India: From Midnight to the Millennium and Beyond, a thought-provoking book which even President Clinton has read. Interestingly, Tharoor is an Indian national who has probably lived outside of India longer than most immigrants!

As an astute observer of immigrant life in the US, how does he explain the connections that Indians create with their home country? He feels that there are two broad phenomena at work: “On the one hand, modern communications means that immigrants never really have to sever their links to their homeland, unlike the Irish in the 19th century or the East Europeans in the early 20th, who lost direct contact with the families they left behind.

So all Indians here, almost without exception, remain connected to family or friends back in India. Their atavism can sometimes take the form of support for extremism – sending money to fundamentalist causes of whatever faith. That, thankfully, is dying down after the follies of the 1980s and 1990s.”

The more interesting phenomenon, he feels, is that so many members of the younger generation, born or at least raised here, are actively seeking to develop their own links to their ancestral homeland: “You have kids going back not just for the ritual obligatory holidays with their parents, but returning on their own for Junior year Abroad, or taking fellowships to study or work in India, or spending a summer or even a year assisting an NGO doing humanitarian work in India.

Giving Back…

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]t’s amazing how much young Indian-Americans are learning and how much they’re giving back. And their involvement means that India is being changed by their contributions, and America is being changed too, because these kids, however American they are, will always have a major streak of India in them.”

Indeed, immigrants and their children are forging their own connections with a changing India. The immigrant generation has been more observant of the rituals and special days – the India Day Parades and celebrations from New York to Atlanta to California are largely their initiative and their attempt to share this special day with other Indians as well as the larger mainstream community.

Indu Jaiswal, a community activist in Long Island, New York has coordinated with the Town of Hempstead to organize a big birthday bash for India at the Town Hall every year, hosted by County Supervisor Kate Murray, with Indian cultural entertainment and food. It is a way of telling Americans about the DNA of their fellow Indian-Americans and such celebrations are replicated in many parts of the country.

The younger generation, active in so many different professions, is also bringing their own thoughtful approach to India. They celebrate the successes but also think about the lackings – and how these can be redressed. Says Khandelwal, “To immigrants and their children, Indian independence can mean so many things, including where India is in the community of nations as an independent entity.

There is a growing awareness that India is progressing and making its mark in the international community but at the same time there is awareness of the glaring instances where there are huge limitations and things we need to take care of, such as the poverty, the need for education.”

She sees many immigrants and the second generation involved in efforts to make a difference in the home country through initiatives and funds, and in finding ways to serve the home country.

She adds, “I think in doing that they are also trying to find who they are, understand their own identity and what their connections with India are.” She feels it is imperative that India make efforts to engage this young generation and give them reasons and opportunities to interact with the home country.

India on the World Stage…

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]sk Shashi Tharoor if India’s changing and escalating place on the world stage has changed Indian immigrants’ opinion of it, and he responds, “Yes, and they too are a part of it. I have no doubt that there were some who were embarrassed or apologetic about their Indian ness in the past, when India was seen as a country of begging-bowls and snake-charmers.

Today, the India of software gurus, savvy high-tech entrepreneurs and designer razzmatazz in Bollywood and beyond is an India that they are all happy to be identified with — along with Indian music, Indian cuisine, and Indian literature. But NRIs are both producers and consumers of this sophisticated popular Indian culture, and what they’re doing with Indian inspirations in the West – from creative fusions of dance and music to world-class movies like the Namesake – are also vital to the perception of India’s enhanced standing in the world.”

He adds that if twenty years ago Indian-Americans were self-conscious about wearing ethnic dress and anxious to blend in, today they are much more comfortable doing so, knowing that they are sporting attire that Madonna and Goldie Hawn have made fashionable!

Isheeta Ganguly is one of the second generation Indian-Americans who are etching out their own relationship with a country that is far away – and yet very near now. Her parents came to the US in the early 70’s as part of the predictable “brain drain” from India. Natives of Kolkota, her father was a chemical engineer and her mother an English professor. Their journeys took them to Turkey, Japan and Indonesia, finally arriving in the US.

Isheeta Ganguly is one of the second generation Indian-Americans who are etching out their own relationship with a country that is far away – and yet very near now. Her parents came to the US in the early 70’s as part of the predictable “brain drain” from India. Natives of Kolkota, her father was a chemical engineer and her mother an English professor. Their journeys took them to Turkey, Japan and Indonesia, finally arriving in the US.

Ganguly spent much of her childhood in New Jersey. She recalls, “. While growing up, it felt as though we celebrated our Indian-ness, our food, our costumes, our music, our dance, privately, in our homes or in closed community events while we simultaneously touted our American-ness to the best of our ability to the world outside.”

She adds, “Being Indian was wonderful within the home, but pejorative in many ways, outside the home, simply because it was so foreign. As first generation immigrant parents, our parents did a Herculean task of reconciling this new world despite the deep emotional tugs that yanked at them, while giving us the sense that everything was moving along just as it should.”

Here one has to give credit to the immigrant generation which had to make its way in the New World while holding on to the values and cultural norms of the old. Non –resident Indians have often been derided as Non-Relevant Indians, as people with tenuous links to the home country. Tharoor in his new book has a whole chapter devoted to ‘NRIs – The Now Required Indians’ – for in the new India the highly successful and talented immigrants have acquired a new cachet and could be partners in India’s prosperity.

Coming Full Circle….

[dropcap]C[/dropcap]an India capitalize on its diasporic sons and daughters and utilize their talents to further India’s success story, especially finding a role for the generations of young Indians who are born in America? Says Tharoor: “I think India is already doing most of the right things — from the Pravasi Bharatiya days and awards, to the new “overseas Indian citizenship”. But India is not just the Government — it’s a society, a civilization. It’s up to young Indian Americans to be inspired by it and to seek to enter it; as I said earlier, I’m impressed by how many of them are doing just that.”

For Isheeta Ganguly, the links to her distant homeland, were forged through the magic of Rabindrasangeet. “My love for India grew during my frequent childhood trips to Kolkata. My grandfather, Santimoy Ganguli, was a renowned freedom-fighter during India’s independence movement and a close affiliate of Subhash Chandra Bose,” she says. “ My grandfather taught me my very first songs, which were patriotic tunes, at the age of four, including “Jana Gana Mana” and “Bande Mataram”. These melodies and rhythms deeply resonated with me, particularly as I would travel back to my other world and other life, in New Jersey.

The trips to and from India were a critical part of what shaped the journey in defining the Indian American experience for Ganguly. “Growing up in the ’80s, we all seemed to be fumbling along the path of defining what ‘Indian American’ meant, hoping to find more of a balance between our lives at home and outside,” she says. “ Our realities were often jarring and silo-ed in separateness. My music provided a thread of continuity in bridging these two worlds. As I continued to learn Rabindrasangeet during my trips to India, I found a home of sorts in my music which gave clarity and provided comfort in making sense of some of the contradictions.”

. Zeyba Rahman believes that some second generation children have mixed feelings toward the home country: “I have seen children of my friends who are completely assimilated into American culture but their parents have really encouraged them to know about their culture and their country. They are full of questions bout India, and some even take up studies about India in college.

Of course there are some kids who don’t want to be connected to Indian culture at this time but I feel eventually as you go on life – and I have seen this in myself – you do want to re-connect. And I have seen this in kids who shut down their Indian side but then when they start working and have families of their own, they want to know more about their culture and connect. It’s a cycle – a cycle of development in the community.”

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]ndeed, it’s an ongoing process and now with India so much in the public eye, it’s easier on these kids. Growing up, many of them had to sit through classes where the text books depicted India as a downtrodden third world country.

“It’s changed radically now in how mainstream Americans view India, how business people talk about India, how politicians talk about India,” says Rahman. “ India is very much in the spotlight and the Indian community here is a very successful and educated community.”

Working as a management consultant in New York in the late nineties, Isheeta Ganguly could sense the beginnings of an Indo-US movement, which resulted in an unprecedented dialogue and exchange in almost sector, notably in business, science, education and the arts. She says, “It became incredibly exciting to be part of the generation witnessing what seemed to be the path breaking story of our lifetime.”

A noted singer, Ganguly has several albums to her credit, including the latest, ‘Call of the Young’ (Nutan Joubaneri Duth), directed by her guru Suchitra Mitra. Three years back she took the unprecedented step of moving back to the home country, completing a circle which started with her birth in Kolkata.

Moving to India, the distant home that she only really knew from afar, has been an exhilarating experience. The landscape is ripe with professional opportunities for Indian-Americans to go back and investigate. She talks of the mushrooming and boom of metro living and the ease with which one can float back and forth: “ Finally, we’ve arrived at a place where we don’t have to choose one world versus another. In our globalized realities, we can pretty much have both, at the same time without giving too much up on either side.”

She adds “When I moved to Mumbai three years ago to set-up and establish the Indian version of Sesame Street (‘Galli Galli Sim Sim’) I was amazed by the professionalism I encountered amongst decision-makers across all sectors – corporate, civil society, educational institutions alike. The energy, drive, and passion to make ‘India Inc’ succeed were infectious. There seemed to be a desire in India to take the best from America but to make it work in a way that made sense to the Indian context.”

The Power of Pluralism…

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]t the core of this whole phenomenon is India’s greatest strength – its pluralism. Sometimes it gets obscured by occasional missteps but it is still India’s heart. Assad Rahman saw glimpses of it even during the tough days of India’s partition. He was one of only two Muslim students at St. Stephens College during the riots and he remembers, “The whole college supported me – some of my friends lent me their clothes as I had none of my own. Everybody was so kind. The bearers in the college were Paharis, and most of them were Brahmans and they were so solicitous of me – they treated me like their own child. And that I can’t forget.”

This wonderful pluralism is finding its way into every arena and makes India even more attractive for young Indian-Americans who have grown up in the melting pot of America.

Assad Rahman’s daughter Zeyba explains how this pluralism is filtering even into India’s music. “Having just come back from India where I was producing and recording a CD for a European label, I find new music is constantly developing in India, with the Internet, and markets opening up.”

She says the flow of music from India to the west and from west to India has increased and so there is a new music, a hybrid evolving and then there is also Bollywood sampling western music and applying it to its song and dance routines; rap is being mixed with bhangra and other Indian traditions. This fusion is happening not only in music, but also in visual arts, in the performing arts, in dance. Dancers who have studied the Indian traditions in India or in America are now applying that vocabulary to other forms, so it’s a constant back and forth.

Rahman works in many parts of the world with different cultures in multiple media, and says, “What I find amazing about India is that it has the capacity to transform what it takes from other cultures to make it uniquely its own, at the core it is Indian. It absorbs all these influences from around the world, and yet the Indian cultural identity is so strong that it can absorb all these influences and then morph into another form of uniquely Indian cultural expression.

India and Indians have the capacity to allow different cultures and traditions to wash over them like waves – and a very vibrant, uniquely Indian expression emerges from that.”

Which brings us full circle to the question: what does it mean to be an Indian-American? In his book, Tharoor asks: What does it mean to be an Indian? He answers it this way, “Our nation is such a conglomeration of languages, cultures, and ethnicities that it is tempting to dismiss the question as unanswerable…sixty years after independence, however, it will no longer do to duck the question.

For amid our diversities we have all acquired a sense of what we have in common: the assumptions, the habits and the shared reference points that constitute the cultural and intellectual baggage of every thinking Indian.”

Surely, every immigrant traveler has also transported these assumptions, habits and reference points to America in their luggage, and they are now mapped into the DNA of young Indian-Americans. These commonalities – matters of the heart and soul – are what glue Indian-Americans to their homeland.

this article was written in 2007.

© Lavina Melwani