AIF-Yale Summit:

India Today – Challenges and Opportunities

What happens when you manage to gather critical thinkers like Indra Nooyi, PepsiCo’s Chairman and CEO, the many faceted Fareed Zakaria, Kapil Sibal, India’s Union Minister for Human Resource Development and Richard C. Levin, President of Yale University all in the same room?

You get some thought- provoking conversation about where India is going and the challenges along the way. This lively brainstorming session happened at India Today: Challenges and Opportunities, a summit organized by American India Foundation in partnership with Yale University, and US-India Business Council.

As Chandrika Tandon, a trustee of AIF, put it, the event was a combination of “People that are serving India – inside and outside – and building bridges across the two countries in multiple sectors.” She introduced American India Foundation, which in partnership with various NGO’s serves 1.5 million under-served people in India in the areas of health, livelihood and education. Tandon calls it “the preeminent coming together of Diaspora philanthropy – the largest collective platform for India anywhere in the world.”

Other partners were U.S-India Business Council, an advocacy group which brings business leaders together from the two countries and which, in the spirit of social responsibility, has mounted initiatives in education and vocational training. The catalyst for the event was Yale University and the Yale India initiative.

“Yale has committed major resources to become a preeminent center for the study of India, to engage with the Diaspora, and to train leaders in different segments of society,” said Tandon. “It has collaborations in multiple areas with India. The Yale–India Initiative is a huge commitment to make all this happen.”

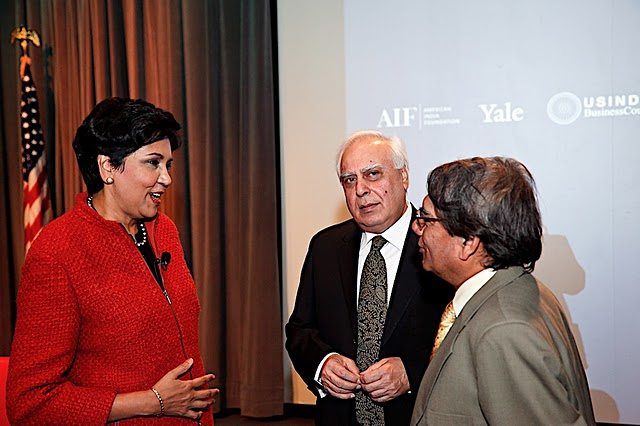

Talk Fest: Sibal, Nooyi, Zakaria, Levin & Mohan

What followed was a freewheeling and lively discussion with Minister Kapil Sibal, Richard Levin and Indra Nooyi of PepsiCo which is involved in private-public partnerships in India in the areas of ecology, waste management and agriculture. They were joined by Dr. Rakesh Mohan, former Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, who is currently a professor at Yale University. The talk was moderated by Fareed Zakaria, who until recently was the Editor of Newsweek International and is now Editor-at-Large of Time Magazine. He is also a Washington Post columnist, and also hosts CNN’s flagship foreign affairs show, GPS.

What is India doing right – and what is it doing wrong? Can it overtake China? And what about privatizing public works to fix the infrastructure? Will there be enough teachers? What about the health and hygiene challenge? So come be a fly on the wall and listen to where India is headed and what changes are planned for the future…

Excerpts from the conversation:

What is India Doing Right,

What is India Doing Wrong?

Fareed Zakaria: Indra, you travel all over the world, you are running one of the true multinationals, and you probably operate in 150,170 countries. When you look at what is going on in the ground in India, what is India doing right, what is it doing wrong?

Indra Nooyi: India is one of those markets which we group as a must-invest market. You cannot not invest in this market because there are so many things about India that makes it a very attractive destination. One, it has got the great demographic advantage. There are a billion people there. Where mouths are – you have to feed them, so we think India is a very important market.

India has got a phenomenal workforce – not enough of it – but a phenomenal workforce and we use India as an expatriate center. We have lots of Indian executives working in many, many parts of the world. So India is a very strong development center for us. India represents years of growth. I think if we look over the next 30, 40, 50 years with the young people, – large portion of the population being young and all of them aging- we see a growth market for us for the next 50 years at least, which is not the case in many of the other markets that we participate in.

And lastly, India is exciting because a lot of innovation comes out of India that we can take to the rest of the world. Whether it is an equipment innovation, it is ideas; it is even advertising campaigns that come out of India are absolutely brilliant. So there is so much going for India and India is clearly a must-invest, the top line growth market, so we are in India for the long haul.

Indra Nooyi’s Wish List…

Now let me tell you what I wish would happen in India. To talk about it is a tough one because I have got one foot there, one foot here and whatever I say is in not intended to be a criticism, rather to talk about India constructively in terms of what can be done better, so you can attract more investment and India itself can develop faster. Let me start off by saying that for industry trying to invest in India, the first biggest issue we have is the infrastructure, it is – if I use the word ‘ appalling’ – that would be a bit of an understatement now.

When I go to India, you know, many people say why don’t you look at the five-lane highway between Bombay and Poona, why don’t you look at the 800 km that have been built in some diameter or triangle or whatever, but you know what? We don’t look at diameters and triangles. When we talk about reaching every nook and corner of India we need an infrastructure: roads, we need rail, we need octroi duties harmonized. We need an infrastructure corridor in India that works, we need power 24 hours a day in every part of the country, and we need water. We are willing to help but we need access to water, and the basic infrastructure in India still needs a lot of work.

Now I am not saying that developments have not been made but it is not as fast as it needs to be and unfortunately every project that is started, there is too much slippage and we see it. So infrastructure is the first one.

Second, it is interesting, there is almost a paradox: In India we have access to a lot of manpower, there is no shortage of manpower, but it is not the right skills. The manpower that we get, even if they have an MBA degree or an engineering degree, unless they come from the top tier schools they are not as qualified as they need to be. So you almost have to retrain them inside the company. So I think we have to invest heavily to take this manpower that is available, that is very bright, but we have to make sure that we educate them the right way. It is critically important.

And the third one that I mentioned – and I am only mentioning the top three – is health because there is so much of India that needs to improve from a cleanliness perspective, from hygiene. We have lot of diseases that spread through India and the thing we worry about the most is how can we get people to stay in India and not move out of India, especially when we train people up to a certain level and we want them to stay there and grow the country. We want them to feel good about living in India, we want our senior executives to feel good about living in India.

We think that if you improve education you can improve the hygiene standards in India and you can reduce incidence of disease and the economy itself will become much healthier going forward. So again, let me summarize by saying, a must-invest country with great opportunity. I think India knows what its issues are; I think the ‘say do’ ratio is a little bit out of whack.

Fareed Zakaria & Rakesh Mohan on India & China

Fareed Zakaria: There is a friend of mine who has factories in both India and China. I was asking him what is the big difference between operating in India and China? He said it is very simple: “In China I can’t get my managers to talk to me, to tell me what is going wrong, what is happening, what are the problems. In India, I can’t get my managers to shut up.”

So let me ask you, Rakesh, another question at 30,000 feet, which is you have been there from the beginning, people think of Manmohan Singh as the father of reform, but there are a number of bureaucrats around him who were really the uncles of reform in India and he was the father.

So the argument goes something like this: The biggest problem India faces is things are going too well. Governments only reform when their backs are against the wall, in crises. If you think of the East Asian crisis, it is the perfect example where all those East Asian countries did massive reforms.

Then in India you are getting 7-8% growth without doing very much and the government reform has stalled in India and so there are all the kinds of issues Indra is talking about need some kind of major push, some kind of heroic, more than just the incremental push and there is no political will to do it. The government is sitting pretty, the BJP is imploded and so they don’t face any real pressure. Can you get to the next stage with just the tinkering that is going on now?

Rakesh Mohan: Fareed, I think that if you look back over the last 20 years after the original burst in 1991, at any given time you would have said the same thing, since 1991, that not much is happening right now. If you took a survey of the newspapers in any of these years you would say exactly the same thing.

Now you can’t have a burst in reform every year, right? So it has to be now much more incremental reform in every area and I think Indra mentioned exactly the problems that we have. I would agree with you, however, that in some sense we did the easier reforms earlier, which is what I used to call ‘reforms by announcements’, that is you could say I am delicensing, I am removing trade barriers, I am devaluing the currency – all that we did in 1991.

Now what we have are all process reforms which can’t be done by announcements. Of course, Minister Sibal has made announcements on education reforms but I know that he is there for the full running and doing those things, carrying through all the legislation, but those are all difficult things to do.

I am now chairing a committee on long-term transport policy. Now, that is a ‘say-do’ problem there, but I am only chairing the committee which will ‘say’ what could be done in the long term and the ‘do’ will be someone else. But the point is that these issues are being addressed and I think that also in the education sphere, right from the primary education to the top higher education, I think more has been thought about, looked at, and acted on in the last five years than in the previous 15.

And the one thing I would say – I do believe that not enough attention is being given to sanitation and health. In other areas the issue may be that we’re not doing enough as yet but you are aware of it, but I think it is sanitation and health we haven’t even begun the discussion, and I think that is a very serious area. Even in other poor countries you do not see the kind of sanitation that we have in India and also the kind of health problems we have.

Fareed Zakaria: And which is why in the human development index India scores very poorly…

Rakesh Mohan: That is certainly the case and I think you will not get a demographic dividend if you don’t have the right health, particularly the age of 0-5, and then the education from the age of 5-20 and I think that is absolutely correct, but as I said, in the other issues there is thinking, there is some action. We may be slow, we may perhaps be faltering every now and then, but the awareness is clearly there, – but in sanitation and health it is not there.

Fareed Zakaria: No, I have often thought that people talk about the demographic dividend and it is obviously real, and it is, as Indra said, the motor driving this economy in some sense, but it is worth remembering that India has had good demographics for a long time and when you have bad economic policy, good demographics can be a catastrophe.

Richard Levin: Yes, health and education are two of the three factors. Rakesh is right – reform does not happen overnight and there is a substantive cumulative effect. If you could have found a prominent Indian-American businesswoman in 1990 and asked the question that Fareed asked Indra – what are the biggest barriers to India, what are the biggest problems – the answer wouldn’t have been infrastructure, education, and health. It would have been barriers to foreign investment, bureaucracy, licensing, internal trade barriers; millions of obstacles to doing business in India that, while not perfected by now, are a lot better.

Indra Nooyi: They wouldn’t have asked a businesswoman!

Fareed Zakaria: Kapil, How do you respond to this? Put your hat on, not just as the minister of human resources – you are minister of science, you have been in the Cabinet for a long time, do you think that the Indian government… I mean the way I would respond to all this is, yes it is all true but if you think of this in terms of benchmarking against China, the Chinese infrastructure, or China’s current investment in education, India is way behind and frankly it shows. You know, I mean there are still people like Kamal Nath who talk about the race. There is no race – the Chinese economy is three times the size of India’s and is growing faster even now. You know, simple compound arithmetic will tell you, if this is a race, the outcome is pretty much determined.

Kapil Sibal: I think that when you are in government and you are dealing with the politics of India. you realize how difficult and complex it is to move the reforms agenda forward. I mean, on any piece of legislation, it is not the Democratic Party or the Republican Party, you have got different parties in different states we have to deal with and then we have to look at their constituencies. They look at their constituencies entirely differently from the way we look at the national constituency. So we have to build bridges with them. Now that process requires us to actually persuade them to accept things – there is a different mindset. How do you change that, how do you persuade them to accept your position? These are very complex issues.

Then you have the constitutional issue. You talk about health and education. Where does health and education reside in terms of implementation? It is in the state government. They have to produce the resources for health and education. They have limited resources, we are a 1.4 trillion dollar economy – China is a 4 trillion dollar economy. The methodologies are different, the political system is different, and so it is very difficult to compare the Chinese progress with the Indian progress.

What I have to say is that I believe that we got our second independence in 1991 and if you look back in the last 20 years I think the progress, considering that we had to deal with those disparate constituencies and take the reform process forward, it has not been too bad. I accept that there are issues with infrastructure, but look at the infrastructure in 1991 and look at infrastructure today. I mean, I landed in JFK a couple of days ago and I was proud of the fact that we built the Delhi airport which is 10 times better! Look at our airport in Hyderabad, look at our airport in Bangalore. I mean these are world-class airports. And you are talking about 1.2 billion people and you are talking about 20 years. How long did America take to build its infrastructure? – Many more.

The problem is the expectation is that we must do today what America took a hundred years to do and somehow we must change the system and get it to work, but the problem is in a democracy it doesn’t happen like that, especially in a complex democracy like India. I don’t think there is any other democracy in the world as complex as the Indian democratic system is. Then you have a very strong judiciary and of course you know people who belong to your media community – they tear us to shreds everyday!

Fareed Zakaria: Yes, we are doing better than 1990, I mean 1990 Indian infrastructure was hell. What I am saying is if you benchmark against what is happening in China, what is happening increasingly in Indonesia, do you feel as though you are managing best?

Kapil Sibal: Well I don’t think we are managing the best way we should manage, I accept that. But I think given the situation that we are in, we are managing pretty well. Take for example, you want to acquire land for the purposes of a road. People will go to court immediately, they will get a stay from the court. Now what can the government do? You have to go to court. Court processes are slow and it takes years to get a judgment. Then you go up and appeal. So what do you expect the government to do? We can’t drive roughshod over people. We don’t have the authority to move people overnight from one place 20 km away and say you have to live here. If we had that authority, I think infrastructure would be built much quicker, but the question is do we want that kind of authority to run that kind of risk? I don’t want my country to be like that. I would rather be slow in our progress but be sure about where we want to go.

Fareed Zakaria & Kapil Sibal: India’s Children

Fareed Zakaria: Let us talk about your primary area of responsibility which is human infrastructure. If you look at the world, the World Bank did a great study on the Asian economic growth in the 1990s and you realize when you compare all of them, that the only common factors have been basically investment in healthcare and education. That other than that, Hong Kong was totally free market, South Korea had lots of tariffs, Singapore had a lot of industrial policy, that there was enormous variety, but the commonality was that all these governments had invested in healthcare and education. Where is India, in your opinion, in terms of the basic issue of this investment?

Kapil Sibal: It is a big challenge; I have sleepless nights thinking about it. It is really a big challenge. I have been able to get two lakhs thirty one thousand crores to be invested in the next five years on elementary education alone, so you can imagine the kind of numbers we are talking about. We have 220 million children who go to school and only 40 million children reach college out of 220 million.

Imagine a scenario where you know 200 million children don’t go to college; imagine where India will be in the next 20 years. It is frightening. They won’t have jobs, they won’t have skills. Whatever they do, what will they do? And it’s a global issue, it’s not just a national issue. So, therefore I think we need to invest hugely both in the health sector and in education. That’s the only way forward. We have to make sure that there is universal education in the next 10 years.

Fareed Zakaria: Is that a realistic goal?

Kapil Sibal: Yes, it is realistic and universal retention rate. And what that will do is bring the kids going to college from 40 million to 60 million, and that then would involve building another thousand universities and another 50,000 colleges over the next 10 years. Now that’s a mind-boggling thing.

And again, education is in the state sector, right. Responsibility is not with the federal government, higher education to some extent is. Which is why the reform process – allow more investment, allow the private sector, allow public private partnerships, free up the system. That’s the rationale for all of us.

Fareed Zakaria & Kapil Sibal: Reforms in India

Fareed Zakaria: Describe the state of the reforms you have proposed.

Kapil Sibal: In the first 100 days I said I will have all the bills drafted, which I did, and we moved the Cabinet. We have unanimity in the cabinet, so all the bills are now drafted, which will restructure the higher education process. The right to education was the first legislative move that we passed in parliament and it is effective April 2010 and now we are getting the state governments to actually move forward. So the education tribunals bill has been passed in Lok Sabha, it will be passed in Rajya Sabha in the winter. And the other bills which deal with education malpractices and accreditation to ensure quality as well as the foreign education providers’ bill will hopefully either be passed in November or definitely before the next academic year. So, within two years we would have restructured the entire education sector. And remember there is a crisis in the sense we realize that if don’t move fast enough we are not going to be able to get those institutions in place.

So we are not going to be able to empower people. Unless you have education, all the other things will not fall in place. That is what we need. In the health sector, I think, the process is a little slower. But again, as I said, we need to take the states on board. And health is a far more difficult thing to implement than education. You can actually send children to school, but how do you bring healthcare to families? It is a far more complicated issue.

Then there is the Universities for Innovation Bill. We are going to set 14 government universities for innovation as well as any number of private universities that wish to set up. The concept is that the 21st century is going to throw up challenges which need to be addressed, and they cannot be addressed by the university system that has served the 20th century very well. And what are those challenges, what are the new 21st century’s cities going to be like? How do you build a new city which is sustainable? That involves economics, it involves social planning, it involves high technology transportation, science and technology issues, water management issues. And once you build the 21st century city, it can be replicated in the other parts of the world.

So take, for example, you want to set up a university on design. You know, you can have a chip design, architectural design, you can have textile fabrics design. A university built around the concept of design. We want innovative ideas to come within the education sector to deal with the challenges of the 21st century. Again, we want anybody in the world to come. In the Innovation University structure we are going to allow foreign faculty, we are going to allow foreign vice chancellors, no control on salaries, and the management structure and the governance structure would be as you want it. It can change from one Innovation University to another.

Richard Levin on Partnerships with Yale in India

Fareed Zakaria: Rick, when you listen to all this how does it strike you and what can Yale do in terms of partnerships that would be transferring know how, helping with best practices?

Richard Levin: Well I think Kapil is completely on the right track, and I think his vision and his objectives are just exactly what India needs. India has so much talent, the Indian diaspora has so much talent and yet there is not a single Indian university in the top 50 in the world and that is stunning, given the quality of the IQ and the capacity of the best educated Indians to contribute to their country.

I think to get a few breakthrough institutions being built is actually much easier than the first challenge. It requires essentially a tripling of the share of GDP devoted to education, which is a big number. Now the Chinese did it in a decade. They actually tripled the share of GDP going to education, unprecedented in human history to do that. But the intent is right and surely, I think, Minister Sibal needs to get as much support as possible from this side of the world as well as at home.

Our expertise in Yale of course goes much more helping think about how you fashion higher quality end spectrum of what can you do in terms of building strong universities that are competitive. We have been talking for the past year and a half about these issues and we’ll continue to talk.

We have been doing some work with Chinese universities on this subject and I think that actually we’re seeing some impact and we are certainly hopeful that we can contribute as an advisor and potentially a collaborator in some of these initiatives. We have programs in some of the professions now. Our school of environmental studies has a close partnership with Dr. Pachauri’s Institute for Energy and Resources (TERI) and some of those projects are being expanded to educate the environment officials throughout the Indian government, I think it is a place we can make a contribution. We have a new business school Dean coming next year. who has experience with the University of Chicago of setting up international operations on a much bigger scale than our School of Management has ever done. I know he is ambitious about thinking in terms of being able to do something to contribute.

Fareed Zakaria: You have put forward the possibility of a new campus in Singapore?

Richard Levin: Yes and I should a say a word with that because I have friends in both India and China who expressed disappointment that Yale is now proceeding in discussions with Singapore about founding a Liberal Arts College. I think that this experiment, which will be on a very small scale, just a 1000 students, in the Liberal Arts College on the campus of the National University of Singapore, if we go forward. We are in discussions and hopefully if it works out we will conclude this by around the end of the year or January.

But the idea here is to reinvent the concept of liberal arts education for Asia in the 21st century. I am very excited about it. We do see it as essentially an experiment, how can we create a curriculum that bridge eastern and western thinking, that actually fuses and brings in the conversation Asian and Western perspectives on the sort of humanities and social science side and of course educate people through our capability in science and technology as well.

Comprehensive undergraduate education, non-specialized the way that you hear in this country, two years of general education followed by two years of concentration. We think that kind of education with a flexible interactive prepares students for leadership roles. It makes them flexible and adaptive thinkers rather than narrow specialists who may learn by rote as this is too often the case in Asia today with Asian education to learn by rote, the current state of the art in some technical subject. It does not help you much if you aren’t a believer in the ways of critical thinking and the ways to adapt to new information and the way to be innovative. So we think this is a great concept.

By positioning ourselves in Singapore our hope would be to draw a significant numbers of students from India, from China, and South East Asia so that we can actually create kind of multiplied effect by demonstrating this concept in Singapore. Perhaps within a decade we would be as Yale was in the 19th century in America a model to be imitated. Yale in 1828 wrote the classic state of liberal education and that was hugely influential in founding liberal arts colleges and small universities and private universities throughout New England and West, and even the South of the United States. We had William Swarthmore, dozens of other schools were founded by Yale graduates in Yale’s image.

Vocational Training and Creating Jobs in India

Kapil Sibal: Fareed, Indra raised a very important point about skills and you mentioned that you don’t find engineers with those skills and you need to invest a lot of money. That is really another very big challenge, but I think it is a great global opportunity, because what is happening is that even if we get the gross enrollment raised up to 30 percent there will still be about a 150-160 million children who will not have gone to college, and we need vocational training and skills for that. And here is where the international community has an enormous opportunity.

Take, for example, the hospitality sector. The hospitality sector needs skilled people, but whom they need not pay $60,000 or $80,000 to become competitive and therefore you can set up courses in India, nine month courses, one year or two year courses, vocational training. Take healthcare, nurses, paramedics, lab assistants, artisans, drivers – there is enormous possibility and this is a global opportunity as well because the world is going to need young people with skills and you can actually set up institutions. So I think the greater investment in the short term will be coming into the vocational side in India, and in the long term coming into higher education.

Fareed Zakaria: Well, Kapil, if you really are going to scale at the level you are talking about, there is no way the government is going to have enough money, so you are going to have to have mass involvement of the private sector?

Kapil Sibal: Elementary and secondary education is going to be done. We have got enough resources for that and it is not an issue. Higher education – as it is 70 percent of all engineering colleges are built by private sector. The issue is not that. The issue is that you will have the infrastructure, but not the faculty. We have the schools, we don’t have the teachers.

Fareed Zakaria: But you have enough money for primary and secondary education?

Kapil Sibal: Two lakhs thirty one thousand crores – never in the history. $60 billion dollars, already set aside for elementary education, so the government commitment is there and the money is there, and the government says if you want more we will give you more. Right, because nationally we are committed for 100% retention, because that is the only way that will solve the health problems of our country, the sanitation issues of our country.

Indra Nooyi: I completely agree, but I want India to build those thousands of elementary schools and middle schools. Talk about what industry can do to help, in the software world and the whole technology world India’s flag is flying high.

How can we use digital technologies to provide online education, video education? I was at the Yale Music School where a teacher from Chicago was coaching a student in New England on a very intricate violin piece. If that can be done for music, imagine what can be done to bring elementary school education through online methods. I mean you have online courses for college levels, we can do it in the elementary system too. Why can’t we get the private sector, the great Infosys, the Wipro’s, and the TCS who have these magnificent campuses – maybe we should say, you have to take on a thousand schools via the net.

Kapil Sibal: We are doing that. I was with Wipro the other day, talking exactly the same thing. We have launched a $35 computer, and it is going to be rolled out in January 2011. We are going to bring the price down further; my aim is to give a $10 computer to every child in India. The other thing that we are doing – and this is happening on the ground again – in the next one to one and a half years we will connect 26,000 colleges in India through broadband. We have an ICT mission and we are going to connect 504 universities and so we have already created content by IIT which is open source.

Fareed Zakaria: What is it you need from the India-American community? What can we do to help you?

Kapil Sibal: They must invest in education and health in India. That is what we need from them. We will open up the doors for them and we will do whatever we can to make sure that their investment leads to some constructive consequences and that they are not hassled by the normal bureaucratic procedures. They are looking for actually investing in their homeland to empower their children of future generations that are to come. I don’t think they are looking for profit, it doesn’t mean that they don’t get compensation, they will get compensation. What we hope is that they plough it back into education. It is profit to give to the community and that is what I am looking for.

(Photos: Toni Fiorini/ Courtesy of AIF)