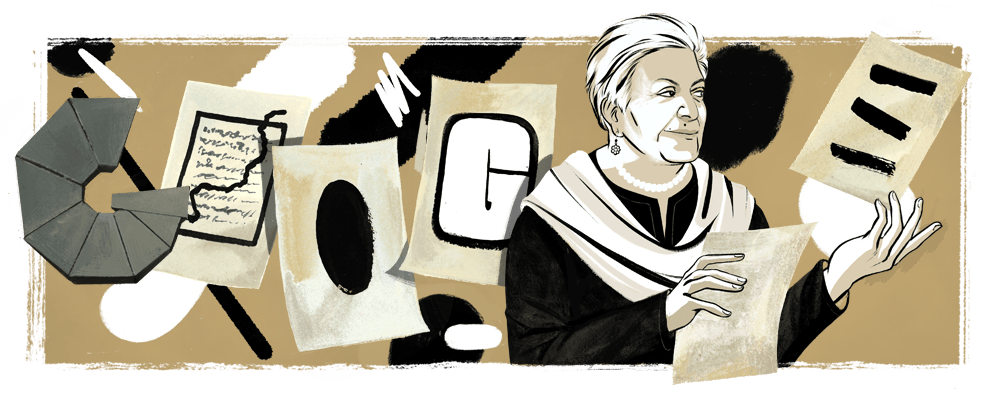

Update: Today is Zarina’s 86th birthday memorial. She passed away in 2020. Google has honored the noted printmaker and artist with its Google Doodle. Read my indepth interview with her some years back.

Photo: Robert Wedemeyer

Zarina – An Exile’s Journeys Across Borders

[dropcap]H[/dropcap]ome and exile are two of the most evocative words in the English language, and they are seared into the work of Zarina Hashmi, noted printmaker and sculptor, who was born in Aligarh in India. Zarina, who goes by only her first name, has been a nomad, a transient who has taken many journeys, crossed many borders. The floor plans of past homes, the many stories of dislocation and the sweet lost language of Urdu are embedded in her prints.

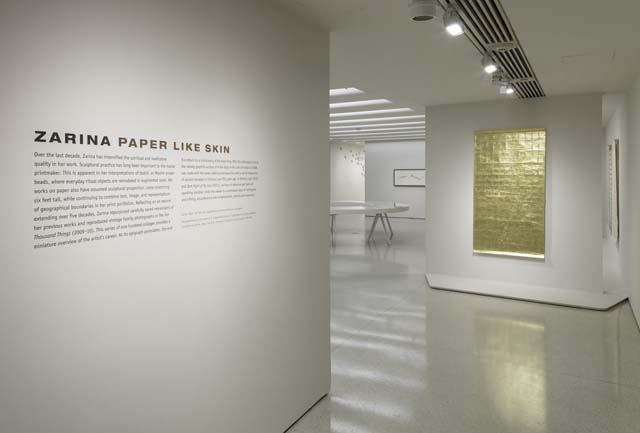

Having worked in relative anonymity for 35 years from her small loft in Manhattan, NY, Zarina, 75, is now suddenly on the international art world’s radar. The prestigious Guggenheim Museum is showcasing “Zarina: Paper Like Skin”, the first retrospective ever of an Indian woman artist, featuring 60 works dating from 1961 to the present. The retrospective, which was organized by and first seen at the Hammer Museum, CA, will be traveling next to the Art Institute of Chicago.

Zarina has participated in the Gwangju Biennial, South Korea (2008), Istanbul Biennial (2011), and was one of four artists to represent India at the Venice Biennale (2011). Her work is currently showing at the India Art Fair with Gallery Espace, New Delhi, and can also be seen at The Armory Fair. Luhring Augustine, NY, is giving her a solo booth at the ADAA Art Show, and Galerie Jaeger Bucher, Paris, will show her work at Art Dubai, and Art Brussels.

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]any museums have acquired her very personal works: In 2010 the Guggenheim bought Untitled 1977, a set of 20 pin drawings; Home is a Foreign Place is in the permanent collection of The Museum of Modern Art, NY; and, as of recently, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Texas. Recently her work has been acquired by Tate Modern, UK; Metropolitan, NY; SFMOMA, CA; and Hammer Museum, CA among others.

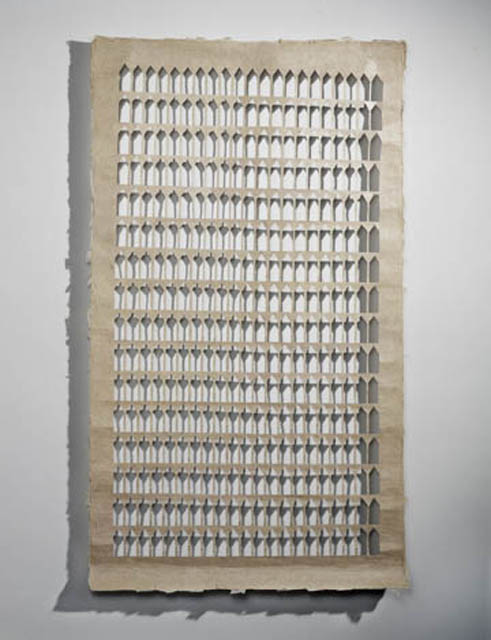

“Paper, with its extraordinary range of tones and textures, forms the core of Zarina’s continually evolving and distinctly independent oeuvre,” says Allegra Pesenti, curator of the retrospective. “With it she expresses the cultural diversity that marks her persona and the notions of boundary, loss, displacement, and home that underlie her abstract vocabulary. Paper has a seemingly fragile surface, yet it supports her manipulations and bears her most vital messages.”

12 Questions for Zarina

What were your thoughts when you first entered the Guggenheim Museum and saw fifty years of your life on the gallery walls?

ZH: I know my work; I know where I was and why I attempted to make a specific piece. I can still feel the texture of the materials I worked with. The fragrance and sounds of the place I was living in and what was going on in my life.

My work is about my life; it is not easy to re-live it and to leave it to the scrutiny of strangers.

How important has each decade of art making been to your life and in turn how has the life you’ve lived fueled your art creation?

ZH: My work is a chronicle of my life, a personal anthology. It is not about decades, it is about each and every fleeting moment I have lived.

“But now I am no longer I, nor is my house any longer my House.”

Although you’ve settled in Manhattan’s West side for 35 years ago, in some ways you are still in your father’s home in Aligarh. You’ve always been a nomad, carrying home with you wherever you’ve gone – through Europe and Asia and on to America. Tell us about those journeys and the gains and losses.

ZH: I don’t feel settled anywhere. I am reconciled to living my life on the road.

“But now I am no longer I, nor is my house any longer my House.” I could not put it better than Federico García Lorca.

In your youth you loved mathematics and architecture and those disciplines are omnipresent in the clean lines and minimalist beauty of your work. And yet there are also layers of poetry and literature in these prints. Can you share about how all these different worlds merged for you?

ZH: I still love mathematics and sciences. I grew up in the vicinity of Agra, and Delhi, looked at lot of architecture of abandoned cities, ruins of homes and palaces. These were not examples of the shining modern architecture of today. Literature, history and poetry were part of my upbringing. I never equate my work with beauty.

The name ‘Paper Like Skin’ fits this exhibit perfectly. Tell us about your relationship with paper and how you make it speak in such powerful ways.

ZH: I have lived with books all my life. I looked at images in books before I could read. I become aware of the quality of paper used in books, its fragility and resilience, having lasted through the centuries, and its portability. Paper was a natural choice. I love organic materials that come from the earth and go back to the earth. I have worked with paper for over fifty years, I have seen it change color, age, and wrinkle just like skin.

There is another relationship here that is almost silent, invisible – the interaction with the paper-makers and the craftspeople who gather the found metals on city streets – how is your life connected with these nameless, faceless people?

ZH: Craft is an important part of my creative process. I have learned a lot working with crafts people in India and in other countries in my travels.

“I love to travel, when the landscape changes out of the window of a moving plane or vehicle, it always inspires me. I think human beings have always travelled and migrated. I think living in one place is not what life is about.”

“Homes I Made / A Life in Nine Lines,” a portfolio of etchings of the floor plans of the homes you’ve lived in is a powerful work from 1997. You have been a daughter, a bride, a wife, a traveler, a teacher, a creator of art but always a student, always learning, always discovering something new about the world around you. Could you share some anecdotes about travel and discovery?

ZH: My first floor plan was of our house in Aligarh where I was born and raised. I made Father’s House after he passed away, in 1994.

After that I decided to make floor plans of all the homes I have lived in in different parts of the world. That’s why I called this portfolio, Homes I Made, the woman as a homemaker. Architecture has been a learning experience for me and I look at architecture wherever I go.

I love to travel, when the landscape changes out of the window of a moving plane or vehicle, it always inspires me. I think human beings have always travelled and migrated. I think living in one place is not what life is about.

You have always hand-carved your own woodblocks and printed your own prints, making the creation of your art very intimate, almost a meditation. If I were a fly on the wall in your loft, what would I see you doing on a typical day of work?

ZH: As Kandinsky has said, “Art is meant to be made by hands and relished by eyes.” I need to touch, to feel the materials. I can’t imagine making anything without my personal intervention.

There is no such thing as a typical working day. Every day brings surprises, I don’t have working days, and I prefer to work at night.

“I am a woman that does not require much explaining. An Indian-Muslim. And if I was not a feminist, I would not be here.”

The world is wont to give many defining, restrictive labels, especially to women artists. You have been identified often as a woman artist, an Indian and a Muslim. How would you like yourself to be seen? You were very active in the feminist circles in the 70’s – is that something deeply ingrained in you, like the markings on a woodcut?

ZH: Labels don’t bother me anymore. When you come from another country, people are curious, want to know what you are doing here. I know who I am! I am a woman that does not require much explaining. An Indian-Muslim. And if I was not a feminist, I would not be here.

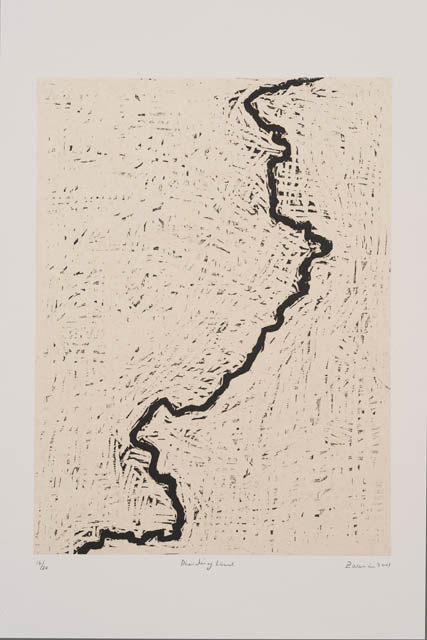

“Dividing Line” is such a powerful work, and those on the Indian subcontinent know the blood and tears behind that work. How much are you personally affected by Partition, that line cutting across the motherland and how much do you think it’s affected your work and your life?

ZH: Partition did effect millions of Indians across the artificial border drown on a map. My family did not suffer any physical harm. However I am the only member of my family who stayed in India. I have carried this scar on my heart for my entire adult life. Now it has come to haunt me in my old age.

“These Cities Blotted into the Wilderness” Srebrenica, Kabul, Ahmedabad, and Beirut – from the personal you have gone to the universal, almost bearing testimony to the devastation in these cities. What do you hope viewers will take away from these images?

ZH: Memory is a burden, we all try to forget. However, one cannot erase history. It is a responsibility of artists to give a voice to people who cannot speak for themselves.

I don’t worry about the viewers, it is important for me to draw a little map of the countries they left behind and print the names as they remember. No one is going to find the way home, but it is a testimony that they had a country and a home and the world remembers.

You have steadily worked, through good times and bad, through anonymity and fame. ‘Home is a Foreign Place’ was done at a particularly tough time when you were faced with eviction from your small home/studio. Tell us about the process of this work.

ZH: I’m not the only one who was threatened with eviction from their homes. Every experience is a learning experience. It made me realize how impermanent homes are. The only homes we can revisit are kept in our memory.

Your two recent works ‘Blinding Light’ and ‘Dark Night of the Soul’ show the journey continues but more inwards. What were you thinking when you made these and where would you like to take the journey next?

ZH: Blinding Light and Dark Night of the Soul are about reconciling with mortality. I don’t know when I will embark on this journey. I do know where it will take me.

“When the journey to God ends, the journey in God begins” – Ibne-Arabi

You have seen both anonymity and fame, and now in fact recognition is coming in a quick stream. What are your feelings about this celebrity status and does it affect your work at all? How would you like your work to be remembered?

ZH: I just want a quiet corner where I can pursue my work. Celebrity status has never interested me. I have no control over how my work will be remembered, the art world is fairly fickle and as they say, dying is not the best career move.

(C) Lavina Melwani

This article first appeared in The Hindu