1258 people reached on Lassi with Lavina FB page – 158 engagements – 32 Likes

2690 impressions on LinkedIn to cover story in Khabar – 60 comments

23 Likes on Instagram

Strong Women: When the ‘Weaker Sex’ is the Stronger Sex

South Asian Women Reinvent Widowhood

An Evergreen story about women’s changing lives…

‘Widow’ is a dismal word which pigeonholes a woman as someone who is leftover, someone frail and unable to fight life’s battles because the main player, her man, is gone. A ‘widower’ does not have the same weakling connotation – he might need a bit of love or a home-cooked meal but is someone who is still commander of his own ship and able to fend for himself. As wives or widows, women have always had secondary roles and nowhere is this more evident than in South Asia, and often these inborn stereotypes are carried by immigrants to the west.

A long time back, hundreds of years ago, there was the horrific social practice of suttee in which the widow was immolated along with her dead husband, on the premise that her life was not worth anything on its own. Over centuries, this practice has been banned but in many cases, especially in rural India and in small towns, widows in India continue to lead a dysfunctional life. In many cities there are old-age homes just for abandoned widows who are often ostracized by the family. Even though India’s first and only female prime minister was the powerful Indira Gandhi, a widow, there are so many things widows can and cannot do in very traditional society.

Here in America, the Indian-American community is a thriving one but many thought processes and rituals are carried over in suitcases along with the spices and folklore. While in India society and norms change slowly, Indian women here tend to be more outspoken and proactive – many came here in traditional arranged marriages but have learnt to take baby steps in leading independent lives – they got jobs, learnt to drive and even went in for higher learning. All along, while bringing in a second income, these women were also the nurturers, the community builders, the housekeepers and the rollers of chapattis. These immigrant women have faced so many struggles in their lives that they seem to have a built-in gene for resilience. For women like that, getting older or becoming widowed is a challenge – but one they are able to face.

Speaking to such older immigrant women, one finds that for them, living totally alone is often a fear: they went from their father’s home to their husband’s home and in India, after widowhood many would live with their son’s family, occupied with grandchildren and family activities. Often their financial life was supervised by the man of the family even if it were a two-income family.

Suddenly the widowed woman has to be the one behind the steering wheel, the one calling the shots and this is happening to some degree in India too where living in big extended families is becoming less common as the younger generation follows jobs to different cities or even abroad.

In Indian-American nuclear families, the plot has to be re-written as the woman, no matter what her age, has to finally learn to fly solo.

Muktiben *(name changed for privacy) of New Jersey is 85 years old, and recently lost her husband who was 90 years old. She had spent many years as caregiver to him but before that she worked in the American school system. She continues to drive and to live alone in her home in the suburbs even though she has an adult daughter and son, both living twenty minutes away – she prefers to live independently and meet her children and grandchildren as the matriarch of the family. They drop in and other extended family members also check up on her but she prefers to run her own ship, something she would never have had to do in India. Recently she took her husband’s ashes to India and stayed with her extended family who fussed over her. Yet she’s back, even though America is a lonelier and harder existence – it is now her home and this is where her children are.

Often Indian-American women, while holding jobs and becoming American, have continued to remain more traditional in their thinking, where the husband is the all mighty superhero. Aparna Bhattacharya, director of Raksha, an Atlanta-based community organization which addresses issues facing immigrant women, has seen this trauma in many women who due to cultural conditioning, depend on the male head of the family for key decisions.

Strong Women: Shumitra’s Story

She recalls her own mother Shumitra who became a widow at 54 and was totally adrift when it came to financial decisions as she had depended on her husband Ashoke, who like most Indian heads of family had made all financial decisions – but had died without making a will. She was frustrated when her daughter refused to take on that caretaker role but in the long run was thankful that she had been pushed to make the tough decisions and gain her independence. After the initial shock, she managed the money and she figured it all out because she had earlier worked in a bank and had also talked to her friends about financial matters.

“Later she told me she had not believed she was capable of making those decisions,” recalls Bhattacharya. “Often fathers and husbands are the enablers – my mother had studied psychology in India but her father had never allowed her to practice. So a lot has to do with what you believe you can do and picture yourself doing. I think women don’t understand the importance of knowing about money, knowing about accounts because they think their husbands are always going to take care of them. So there are a lot of women to whom this is happening, and they’re not prepared because they’re not having these important discussions with their husbands.”

She adds, “In my experience of doing this work, I know it is important for families to have wills, to know about the finances and have access to the bank accounts and other financial resources. If COVID has taught us anything, it is we need to be prepared for the unexpected. I also think it is important for women to have access to their own money.”

Many widows are adjusting the script to suit their changed lifestyles. Kavita*, another woman in her 70’s who got widowed last year in New York, continues to work and drive but while maintaining her own home, she spends the nights at her married son’s nearby home, to be close to the grandchildren and shares in the meals their housekeeper cooks as familial connections are such a strength. In this way, she has the best of both worlds, as she bonds with her grandchildren yet retains her independent lifestyle, non-profit work and large circle of friends. She is not defined by the word ‘widow’ as she continues to be a professional, a mother, grandmother and a volunteer in an education nonprofit.

Strong Women: Rita’s Story

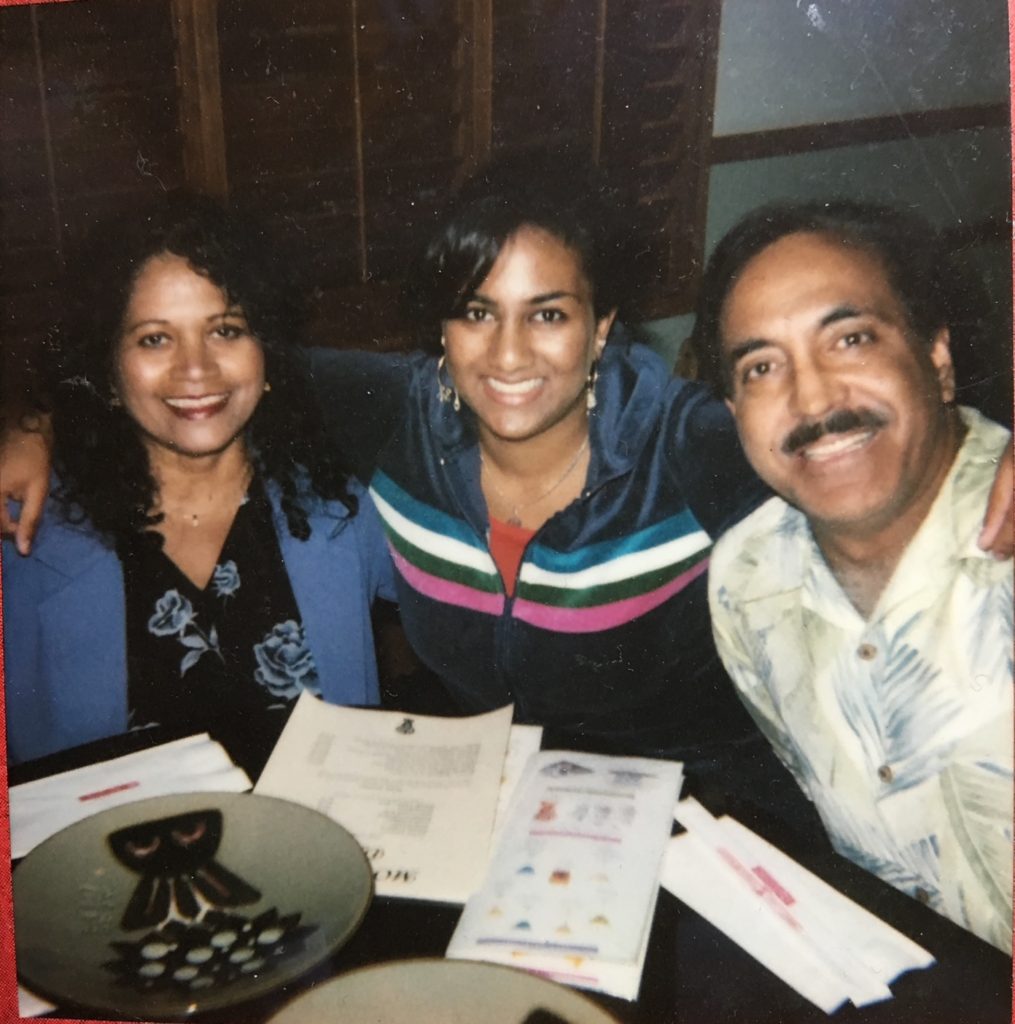

One of the more frightening stories is that of Rita Sadhwani who while in her 30’s, lost her husband in America – without even stepping into America. Her husband had come into the US en route to Canada where his immigrant visa had been approved. Yet before he could travel to Canada, he had a massive heart-attack right at JFK airport and collapsed and died as he boarded a taxi.

A quick-thinking sister and brother-in-law in the US immediately got the young widow and her three children to come from Mumbai to New York and then fly to Canada to actually use the visa. It was a nightmare journey for a quiet docile woman with three small children to board a flight and take on an American/Canadian life back in the 90’s.

Now nearly 30 years later she says it was the best decision she made: she has had a good career in education, her three children are all grown with meaningful jobs and homes of their own. This life would not have been possible if she had remained in Mumbai, surrounded by over-controlling in-laws and conservative relatives. Says Sadhwani, “Before my marriage I had done my masters and had a teaching degree but was never allowed to use it. Even to go for a parent-teacher meeting in my children’s school, I had to get permission from my in-laws. Only when they said yes, I could go.”

Boarding that flight for Canada was the most courageous thing she did and salvaged her own life and that of her children. She was totally alone in Toronto with three small kids and had to adapt to a new world. She had no car, no help and not much money – but education was her strong card and she got a teaching job almost immediately. The tough part was having three small children and having to go to work, especially difficult when the littlest one was teething and had to be left with the older siblings. Education and a strong work ethic won her her independence and secured the future for her children and herself. She says, “It would have been a very different life for me and my children if I had never left Bombay. I would never have been able to shine or use my abilities.”

Sheela’s Story

Strong Women: Sheela Puthumana, an Atlanta-based immigrant, can honestly say that after becoming a widow, she has been to hell and back.

Not being aware of financial matters can really land some widows in a bad place and then it is their inner strength which pulls them out of a tough situation. “I’m the poster child for what can go wrong. And, also of survival – I’m a poster child for that, too.”

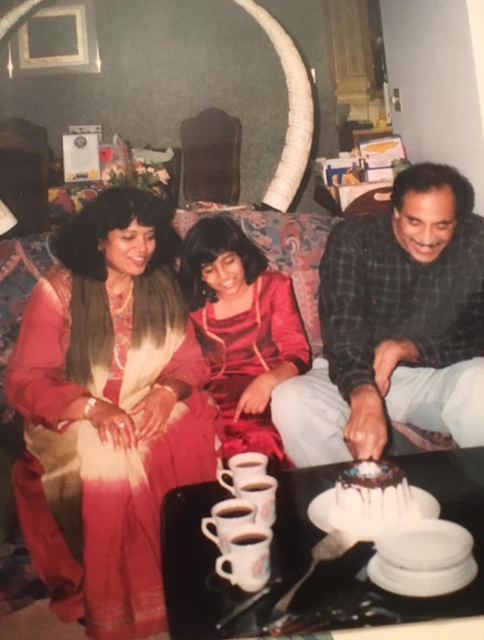

She had immigrated to the US from Kerala in 1966 as a student on a scholarship to St. Francis University in Indiana. Here she, a Malayali Christian, met and married the love of her life, Khurshid Ahmad, a Sunni Muslim from Pakistan. The two, defying religious norms, had been in a wonderful marriage for over 30 years where her husband was a civil engineer and she was the owner and director of a clinical diagnostic laboratory. They had a beautiful house, a young daughter, a flourishing lab, and had traveled the world twice over.

Yet one day, in the course of a few minutes, this beautiful life evaporated.

Early one morning Ahmad was not feeling well and asked to be driven to the hospital. She recalls, “As I was driving, within five minutes of leaving the house, he took a deep breath and left the planet. He was just sitting there still. And I knew he was gone.” She rushed into a nearby gas station and being a medical technologist, gave him CPR as they laid him out on the cold concrete floor. “I knew he was gone but I kept trying, beating his chest and trying to give him breaths.”

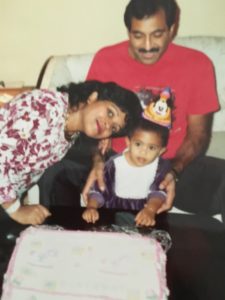

The ambulance came but it was already too late for Ahmad who was just 56 years old. There was no chance of goodbyes for Sheela or her 18-year-old daughter Sophia. Recalls Puthumana : “It was unbelievable, how you can just be thrown into something that you don’t prepare for. I was not expecting him to die – he exercised regularly, played golf, he was seemingly healthy.”

A total nightmare awaited mother and daughter: Puthumana had been so involved in running her lab and Sophia so involved with her studies as a sophomore at Georgia Tech, that all financial affairs had been looked after by Ahmad. He had died without a will and it turned out that the beautiful house they lived in was only in his name. There was no life insurance and no mortgage insurance. Says Puthumana: “We were living like we’re gonna be here for 100 years, you know, no communication about a password or username. Everything came crashing down below ground actually because I couldn’t access anything since my name was not on the property. And, you know, he was paying all the bills from his head – and he died with all the usernames and passwords in his head.”

Suddenly from difficulties in accessing the bank account to getting renters to pay the rent on their rental properties during the economic downturn of 2008 was all heaped on her plate. Her family tried to help with the lab and the mortgage and a few friends stayed around to help. Puthumana says, “I really went through hell – if you don’t have a plan in place, you’re at everyone’s mercy. So I ended up having to foreclose on the rental properties. I had to file bankruptcy for the lab because the debtors were coming up to me left and right. Me and my daughter, we just never looked back- we just picked up the pieces and kept on marching.”

Fortunately for her, after she sold the lab, her medical technologist skills landed her well paying jobs as a laboratory inspector with Atlanta’s regulatory agency. She was later promoted to director for licensing labs and radiology facilities for the state of Georgia. Her daughter Sophia’s education and skill with languages also got her employment with the government in Virginia. With Sophia’s help she was able to hold on to the beautiful house her husband had bought for them. Today, mother and daughter continue to be a team which roots for each other and are friends who enjoy traveling together.

Strong Women: Gulshan’s Story

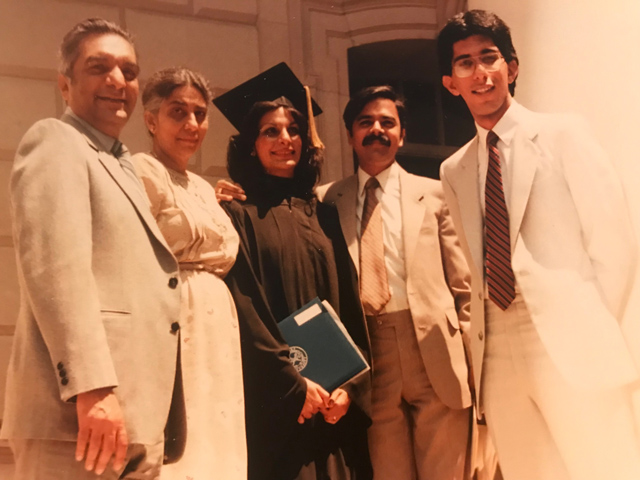

Life has a way of throwing fierce tsunamis at people – and Dr. Gulshan Harjee, also of Atlanta, has had her full share. An immigrant to America, she fled from persecution in Tanzania and got her education in Pakistan and Iran before she earned her medical degree from Emory in Atlanta. Her house job qualified her for a green card, and when she finished her residency, she opened a private practice. Her husband, Dean Delawalla, from Pakistan, had been an immigration lawyer but had left his practice to start a medical supply business, and was day trading on the side. He was her best friend and a great source of help to her. They had one son and finally after several miscarriages, had their daughter ten years later. Harjee is also a cancer survivor, having had systemic lupus which lead to the repeated miscarriages.

The day after her daughter’s fourth birthday, Delawalla was killed at the brokerage house – by a deranged person who had had gone on a shooting spree, killing nine people and injuring many more. This rampage was the worst mass shooting in Atlanta’s history

The world Gulshan and her husband had built up so painstakingly collapsed in those few surreal moments.

Looking through an old New York Times dated July 31, 1999, I found this poignant obituary:

Mr. Delawalla, 52, made his living day trading, showing up almost every morning at the office park. But family and friends say day trading was just his job, not his life. His life, as they tell it, was his wife, Gulshan, a medical intern, and their two children, Faisal, 15, and Shahla, 4.

”They were everything he lived for,” said his brother, Feroz Delawalla. ”He spent almost all of his time with them when he wasn’t trading. In fact, he just traded to have money to take care of them and make a nice home here in America. That was his dream from the day he arrived in Atlanta.”

“The tendency for us is to block out painful incidents. I have very little recall of the funeral,” says Harjee today of that mass shooting. “All I remember is that there were massive numbers of cars, a massive number of people there. It was a huge funeral. And I think the city was also in shock – the whole city kind of just came to rescue us. There were so many memorial services and the mayor came to several of those. It was just a very dark time in my life and for my children.”

Their son Faisal was 15 but Shahla was only four years old and as Harjee recalls; “She would go around looking for Dad thinking he was playing hide-and-seek, and she would say, ‘I’m here Dad, I’m here, Dad.’ We were actually building a house at the time and it was almost ready so we were living in the garage apartment of the house. All it needed was an inspection, some light fixtures, and just the gas and the electricity had to be turned on. This was my husband’s dream house – and it’s painful to think about it even today. I had to keep going because I had two small children. I had a practice on my husband’s business and I had this huge mortgage on a new house. I mean it was just like starting over again.”

Harjee’s extended family is her strength – her mother who had recently become a widow herself came over from Canada to help her with the children so she could go back to work. She says, “My mother was still trying to sort out my dad’s things. She was still trying to learn to live a widow’s life herself and she dropped everything. My sister, who was a nurse in London, had just moved here a year before we sponsored her. So between my sister and my brother-in-law, and my mother, life just went on.”

For most Indian widows, family is the anchor which keeps them afloat, be it long distance or WhatsApp video calls across continents or family members actually boarding a flight to come and give physical support. Often, especially in close-knit communities like the Ismaili congregation, there is a lot of support. Harjee remembers the horrific days after her husband was shot: “I had a lot of emotional support from my whole neighborhood. I had to buy an extra fridge and put it in the garage so people could just come and load whenever they wanted to, any time. There were also so many messages, cards and flowers, donations. It was so overwhelming – if I didn’t have the support of the community and of my siblings and my mother, I don’t know how I would have done this.”

Many widows also get an enhanced sense of purpose after realizing the arbitrary nature of the world. Harjee had made a success of her medical profession and both her children are thriving in their chosen careers: her son is a lawyer and her daughter is pursuing medical studies. She also has turned the difficulties of her life – be it political persecution, financial hardships and medical traumas like cancer into learning blocks for bettering other people’s lives, be it refugees, immigrants or medically challenged communities.

In 2013 she co-founded Clarkston Community Health Center where she serves as chief medical officer, pro bono. This free clinic provides primary and preventive care for the uninsured and economically challenged communities in the metro Atlanta area. She says, “This is where I heal, when I go to meet the widows, when I meet cancer survivors, when I can do for immigrants and refugees and asylum seekers like myself, when I’m able to reach out and do things for them and lift them in their lives. That’s where I am healing as well.” Her latest project, a state-of-the-art patient comprehensive facility that will expand to a three-phase academic campus, will be located in the heart of Clarkston and will serve local marginalized communities.

She has won countless awards and accolades for her caring for the underserved and the forgotten. According to the Georgia Senate which bestowed the Yellow Rose on her: “she has successfully leveraged her vast professional and community service network to establish strong collaborative partnerships with prominent universities and health care institutions and was named Atlanta’s Top Doctor as a result of her dedication to excellence; and Dr. Harjee has established a glowing reputation of renown throughout the state for her personal commitment to the health and welfare of the citizens of Georgia.”

The Aftermath

Love and remarriage are normally not within the plans of most Indian widows who have been conditioned to think of marriage as a forever bond which even death cannot change. While they travel, socialize and work, most Indian widows shy away from new relationships or remarriage. Asha*, a doctor who lost her husband while she was in her 40’s is now in a relationship with a well-to-do young Indian but hesitates to give it an official title or even acknowledge it. Others do organize marriages of expediency so that couples can have a new beginning of companionship and bringing up their children in a new blended family.

As Indian-Americans adapt to the thought processes and lifestyles of America, their attitudes toward widow remarriage is evolving too. Sheena*, 50, who recently lost her husband to cancer, is dealing with it in a very American way by seeing a bereavement counselor and interacting with a group of widows and widowers, seeking companionship and new relationships.

Even in India, where just 50 years ago widows were expected to wear white all their lives and abstain from joy and happy occasions, they are realizing it’s hardly fair to be penalizing women for having lost their life companions and support. Widows are wearing colors and blending into the workforce, merging back into the world.

Women are supposed to be the weaker sex but listening to the stories of these women one realizes they are definitely strong and resilient. Not too many men would be able to survive all that these women have endured – political persecution, health traumas, financial ruin, the death of their spouse and bringing up their children single-handedly. Dr. Gulshan Harjee agrees: “You know, if you told a man that you have to be getting cancer, your spouse is going to drop dead in front of you, I don’t think a man would be able to do all that. They cannot connect with pain. Women’s emotional energies are different, the way we think, the way we prioritize is different.”

As pilots of their solo journeys, these women discover untapped reservoirs of strength and prove they can play the cards life has dealt them.

(C) Lavina Melwani

This first appeared as the cover story in Khabar magazine in Atlanta – Flying Solo: Reinventing Widowhood – Khabar Magazine (www.khabar.com)

This article was written with the support of a journalism fellowship from The Gerontological Society of America, The Journalists Network on Generations, and the Silver Century Foundation.