743 people reached on Facebook Lassi with Lavina page – 44 engagements

Photo Credit: leoncillo sabino Flickr via Compfight cc

Who are the Indian-Americans?

How do they vote? How do they pray? How do they socialize? A new study reveals some intriguing facts about this community

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]hey left their homeland – India – many decades ago. Or perhaps, just recently. They came directly to America from cities across India – or perhaps via Hong Kong, Europe or Uganda. They left thriving livelihoods – or came in search of new ones. They might be immigrants from scattered parts of India – or the American-born children of those very migrants.

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]ack in 1911, a special commission established by the US Congress declared that the earliest of this community were “universally regarded as the least desirable race of immigrants thus far admitted to the United States.” Flash forward over the years to a century later and you find Indians are now one of the most successful and fastest growing communities.

Today they number 4.8 million in America and are an important part of the fabric of the country. They are the Indian-Americans though they go by many names given to them over the years – South Asians, Asian-Americans or even just plain American. In India they are also known as NRIs or non-resident Indians, and at heart, many of them regard themselves as desi or Indian.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap] new study on the Indian American community, which draws on the 2020 Indian American Attitudes Survey (IAAS) puts this community under the microscope and documents some intriguing statistics about them: The study is co-ordinated by Carnegie Foundation for International Peace, John Hopkins University and Penn State University and is based on a paper by Sumitra Badrinathan, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University; Devish Kapur, the Starr Foundation Professor of South Asian Studies and director of Asia Programs at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies Johnathan Kay a James C. Gaither Junior Fellow in the Carnegie South Asia Program and Milan Vaishnav, Director and Senior Fellow, South Asia Program.

The findings of the study are based on a nationally representative online survey of 1,200 Indian American residents in the United States—the 2020 Indian American Attitudes Survey (IAAS)—conducted between September 1 and September 20, 2020, in partnership with the research and analytics firm YouGov

Several thought leaders spoke at a virtual event ‘Social Realities of Indian Americans” which was co-hosted by Carnegie Foundation and The Asian American Foundation (TAAF)

“When I first immigrated to the country, if we saw an Indian person at a grocery store, regardless of shape, size, color, if we figured out that they were Indian, they were somehow over at our house for dinner within three days and then the kids are playing together and we’re family friends for the next decade,” recalled broadcast journalist Hari Sreenivasan in this discussion, and it’s a sentiment many immigrants will recall in their own lives.

“Now fast forward 5, 10, 25 years and you see Indian-Americans all over the place. We also see the infrastructure has split along regional lines, along linguistic lines, and all of a sudden these tiny things that used to be differences in India are now also differences in the US.”

Discussing many aspects of the community, Milan Vaishnav noted that while the overall professional, educational and financial success of the Indian American community is undisputed, there is a lot of variation ,and an incredible amount of inequality. The socio-economic characteristic, he says, “has not inoculated them in any way from the forces of discrimination, polarization and frankly contestation over these very basic questions of identity.”

Indeed, what this study showed is the many nuances and differences within the Indian population which is more of a mosaic rather than a homogenous whole.

According to the study, Indian Americans who are born in the United States are more likely to identify as Indian American (48 to 40 percent) and markedly less likely to identify as Indian (just 11 percent compared to 33 percent of foreign-born Indian Americans). Second-generation Indian Americans born in the United States are more likely to embrace the terms South Asian-American, Asian-American, and the non-hyphenated American.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he study reveals interesting data about the lifestyle and culture of the Indian-American community, and even the differences within the community, depending on the place of birth and generational differences. Unlike many other American communities, Indian-Americans tend to marry within the community. While eight out of ten respondents have a spouse or partner of Indian origin, U.S.-born Indian Americans are four times more likely to have a spouse or partner who is of Indian origin but was born in the United States.

Religion is an important part of the lives of Indian-Americans but religious practice varies. While nearly three-quarters of Indian Americans state that religion plays an important role in their lives, religious practice is less pronounced. Forty percent of respondents pray at least once a day and 27 percent attend religious services at least once a week.

Another fact is that roughly half of all Hindu Indian Americans identify with a caste group. According to the study, foreign-born respondents are significantly more likely than U.S.-born respondents to espouse a caste identity. The overwhelming majority of Hindus with a caste identity—more than eight in ten—self-identify as belonging to the category of general or upper caste.

In matters of political engagement, citizens are more likely to be involved with the civic life and: U.S.-born citizens report the highest levels of engagement, followed by foreign-born U.S. citizens, with non-citizens trailing behind.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n social life, even though Indians are living in America, their social communities tend to revolve around people of Indian origin. The study found that Indian Americans—especially members of the first generation—tend to socialize with other Indian Americans.

“Polarization among Indian Americans reflects broader trends in American society. While religious polarization is less pronounced at an individual level, partisan polarization—linked to political preferences both in India and the United States—is rife,” noted the study. Democrats were uncomfortable having close friends who are Republicans and this was also true of Congress Party supporters vis-à-vis supporters of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

The study further noted that to some extent, divisions in India are being reproduced within the Indian American community: “While only a minority of respondents are concerned about the importation of political divisions from India to the United States, those who are identify religion, political leadership, and political parties in India as the most common factors.”

At a time of racial tension in the country Indian Americans also encounter discrimination. The study also cited that one in two Indian Americans reports being discriminated against in the past one year, with discrimination based on skin color being the most common form of bias.

(This study is the third in a series on the social, political, and foreign policy attitudes of Indian Americans. Click here for the second part of this series, an examination of how Indian Americans view Indian politics, and click here for the first part of the series, which explores how Indian Americans view U.S. politics.)

“We have a huge opportunity here to appreciate and to build America and to write the Asian-American story as part of the American story, understanding the Indian-American community and the social realities of Indian Americans,” said Sonal Shah, President of The Asian American Foundation (TAAF) in the panel discussion. Indians and all Asian-Americans are often made to feel like perpetual foreigners, she said, adding, “We are not perpetual foreigners. This is America, this is what America looks like, and this is how we are going to contribute to America.”

(This article was first published in my weekly column India in America in CNBCTV18.com )

Related Articles:

Meet Indian-Americans Suhas Subramanyam and Ghazala Hashmi

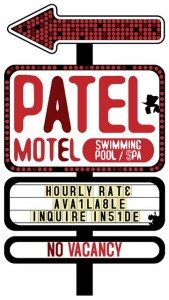

Indian Americans’ Motel Success Story