Indian-Americans in the Political Arena

Almost a hundred years ago, Indian immigrants had a hard time coming into America. The first would-be migrants were turned back, with the derogatory term ‘Hindoos’ attached to them. Facing prejudice, the earliest Punjabi immigrants in California had to battle many forms of discrimination such as the Immigration Act of 1917 which implemented a barred Asiatic zone and literacy requirements. In those early days ‘Hindus’ were not even allowed to own land, let alone become citizens.

In ‘Making Ethnic Choices’, Karen Isaksen Leonard notes that in spite of all these hurdles, Indian immigrants already viewed themselves as future Americans and contributed to appeals for funds for the US effort in World War 1. She writes, “Holtsville Punjabis subscribed liberally to the Liberty Bond Loans in 1918. An appreciative article in Holtsville Tribune listed some 29 Punjabi men who contributed a total of $1500.”

If that can be construed as an early form of political contributions and citizen-sentiments, Leonard has an amusing story of early lobbying as well. “One determined old Punjabi in the Imperial Valley, denied a driver’s license because of his failing sight, got in his car with his 13-year-old son and drove all the way to Sacramento, stopping in Stockton at the Sikh temple on the way to secure political assistance from Punjabis well connected in the state capital. He came back with a driver’s license.”

From those early days, the miniscule Indian-American population has grown to an unbelievable 2.3 million today. According to the Washington-based think tank Migration Policy Institute, Indians are the third-largest immigrant group after Mexicans and Filipinos, and may soon be No.2.

It’s taken a century of lobbying – both formal and informal, organizational and personal – to arrive in the America of 2010 where Bobby Jindal sits in the Governor’s Mansion in Louisiana, Nikki Haley is poised to become the next governor of South Carolina, and where scores of Indian-Americans are serving in the Obama White House and many more are standing for political office.

The Indian-American Political Journey

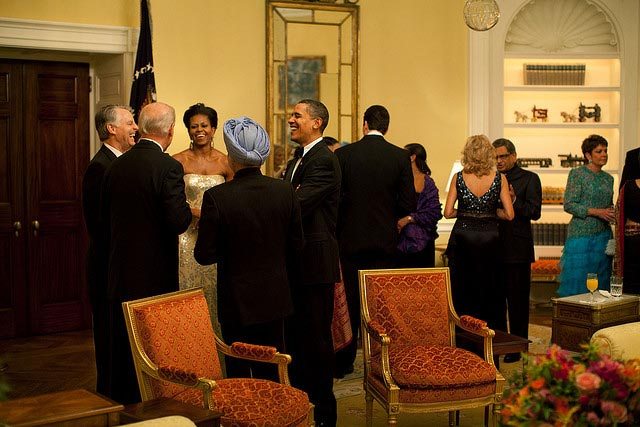

It is an America where Diwali is recognized as an American festival and where the White House hosts Diwali, Baisakhi and Eid celebrations. It is an America where the India-US civilian nuclear agreement – much coveted by India – managed to pass both houses and become law. And yes, it’s an America where it’s finally considered cool to be desi!

None of these changes are the results of the effort of any one individual or group and there is a fascinating array of people and organizations that over the years have made this possible, and are now poised to make the Indian-American community a powerful factor, not unlike America’s Jewish Lobby.

Yet for the most part, for many decades Indian immigrants were not politically active, absorbed in succeeding in a new country and putting down roots. There were rare cases of political activism such as that of Dilip Singh Saund, the first American of Indian origin – in fact the first Asian – to ever become a US Congressman.

“The immigrant generation spent a lot of their time and effort in building their families, getting settled in the new country, and focusing on all things that are American which is very understandable,” says Dr. Walter Andersen, Associate Director of South Asian Studies at John Hopkins University. “It is only when that immigrant generation got to a certain level of comfort that they were able to focus on other things, like getting involved in politics.”

Even as the Indian immigrants were slowly developing political chutzpah, the Indian Government, over the years, hired paid lobbyists in Washington to promote Indian interests in Washington, most recently the noted law firm Barbour Griffith & Rogers which earlier had former Ambassador Robert Blackwill as an advisor.

Indian-Americans & the Indo-US Civil Nuclear Agreement

In the last three months leading up to the nuclear deal, New Delhi also hired Patton Boggs, one of the leading lobbying firms in Washington where the efforts were led by a young second-generation Indian-American lobbyist, Anurag Varma. Former American Ambassador to India, Frank Wizner, is also an advisor to this lobbying firm.

Varma, an attorney in the firm’s international practice, was also lead counsel to a coalition of Indian-American organizations and individuals working in support of the successful passage of the first U.S. law directed towards U.S.-India Civil Nuclear Cooperation. He currently lobbies on behalf of several India-centric clients including the pharmaceutical company, Ranbaxy, US India Business Council, and AAHOA, the Asian American Hotel Owners Association.

According to the Economic Times, after the successful passage of the Indo-Us Nuclear Agreement, India has cut down its lobbying expenses in the US: “This marks a sharp decline of over 97 per cent from USD 180,000 – more than Rs. 82 lakh – of lobbying expenses incurred by the Indian government in the US during the first quarter of 2010, according to the disclosure report filed by Republic of India’s lobbyists with the US administration.”

In Washington, though, lobbying is a fact of life – as necessary as breathing, some might say! It is quite common for foreign governments to spend big bucks hiring lobbying firms and other professionals to help build, maintain and develop relationships on Capitol Hill. Some use in-house resources while others do a hybrid, using in-house Foreign Service officers as well as outside firms.

Indian-Americans have different opinions on this but at least one political savvy desi has strong opinions on this. “The Government of India doesn’t realize the power of lobbying in this country and they spend very insignificant amount for the purpose,” says Narendra Reddy, a Republican stalwart in Atlanta, GA.

“Compare that with the spending on successful lobbying by Governments of Israel and Pakistan. I don’t think the Indian Government appointed lobbyists in Washington DC with their small budgets accomplish any thing. They end up spending what ever small fee they get on hosting dinners for the visiting dignitaries from India which serves no purpose.”

So are there many professional lobbyists of Indian origin in Washington? Anurag Varma, one of the few Indian-American lobbyists, says, “Now that you ask me about it – I am realizing it’s a very small club.” He points out that lobbying is not a glamorous job – it requires self-organization, a thorough knowledge of your subject and finding a way to get in the door. It all has to do with access, education and infrastructure.

“Once you can do it, you understand the rhythm of Washington,” says Varma. “Although in some places in the world lobbying means something negative, in the US it is a very effective way for the people to get their opinions to lawmakers.”

Asked as to whether Indian-Americans and their organizations serve as unofficial lobbyists for India, Varma says: “Absolutely. You see, at the end of the day the Indian-American community and how it is perceived in this country is tied to America’s relationship with India. And to the extent anything that is done to further America’s relationship with India, it helps all Indian-Americans.”

He feels that the derisive tag of ‘photo ops’ placed on the immigrant generation’s political efforts is a little bit unfair: “It was more of a learning curve and the first thing they learned how to do was to get together to spend some money and to become friends of members of Congress. The next step in the evolution has been, ‘So what do we do with these relationships, these friendships?’”

Andersen, who recently retired as Chief of the State Department’s South Asia Division, and has served in India, observes: “All governments do lobbying on their behalf and although the Indian Government has hired lobbyists and they serve a function, I have always felt that the most effective lobbying is done by the community because they have a political impact that the lobbyists don’t have.”

He was involved with the Indian American community in efforts to get the civil nuclear deal passed, and thinks this seminal event, more than any other, galvanized the community and so laid the base for both formal and informal networks to lobby the US Congress on issues of importance to Indian-Americans.

“In doing so, they obviously learnt how American politics operates; they knew how to use pressure to do so,” he says. “Part of the pressure was threats to withdraw funding to Congressmen who were opposed and that’s the way Washington operates, and they did that in several cases.”

He points out that a decade ago the political activity in the Indian-American community was only occasional, something below the surface, but by serving on local educational committees and grassroots organizations, they got a kind of internship in American politics. This went on for ten to fifteen years, and the results are now beginning to show. Indeed, there are many Indian-Americans in the Obama Administration and many more are running for public office.

One of the important tools that Indian-Americans have had in their arsenal is a vibrant Indian media, which according to Andersen, is one of the most effective communication systems. With a broad, often free, circulation, this happens to be the most widely circulated print media of any ethnic group in the US, along with television and radio programming. Indian-Americans have also used the Internet well, and are savvy on forums, blogs and on Twitter. The impact was seen in the case of Senator George Allen’s use of a racial slur on S.R. Sidarth, his opponent’s Indian volunteer, which cost him his seat when the Youtube video went viral and blogs picked up the story.

Sanjay Puri, Chairman of US India Political Action Committee (USINPAC), has seen the change over the past decade and the increased emphasis on advocacy measures. “People are getting much more sophisticated,” he says, recalling the early ‘photo op’ days of political interaction. “There are just so many pictures you can put on the wall – it’s hard to get people excited about a photo anymore – it’s got to be tied to an issue – whether it’s the nuclear deal, whether it’s terrorism, whether it’s HI-B visas, whether it’s discrimination.”

USINPAC provides bipartisan support to candidates for federal, state and local office who support issues important to the Indian-American community. It is working on several fronts, be it protesting a racist ad by the organization Jobs for America or the fee hike for HI-B visas. It’s also actively supporting several Indian-American candidates for public office, including Nikki Haley for governor of South Carolina, Ami Bera for Congress and Manan Trivedi for the US House of Representatives.

“In some ways the Indian community is like the Jewish because it’s a community that cares about strong relationships, not just because it’s good for India but because it’s good for the US too,” says Puri. “We share values and concerns – India’s demographics make it a very relevant country globally and it presents a huge economic opportunity for America.”

Indian community leaders and individual donors have also interacted with senators and congressmen to create the India Caucus in the Senate and Congress, with influential lawmakers rooting for India. The India Caucus is the largest country caucus in the US Congress and was founded in 1993 by Frank Pallone (D-NJ) and Bill McCollum (R-FL). It always helps to have friends in high places, and these Caucuses are a way to get the Indian-American agenda attention. Ten years later the Senate got its own bipartisan India Caucus which was co-chaired by Hillary Rodham Clinton and John Cornyn.

As the community realizes the importance of fielding candidates of Indian origin, several new organizations have taken birth. The Indian American Leadership Initiative (IALI), established in 2000, is a national organization seeking to facilitate the election of Indian American Democrats at every level of local, state and federal government. The organization has a database of active progressive Indian Americans and in 2008 created the 2008 Almanac of Indian American Democrats, a guide to the leading Indian American elected and appointed officials, candidates, campaign consultants, and policymakers. IALI also helps Indian-American candidates become financially viable and puts them in touch with would-be donors.

On the other side of the aisle is The Indian American Conservative Council, headquarted in Washington, D.C. with a Board of Directors and 14 independent state affiliates, which promotes conservative values across the US.

South Asian Americans Leading Together (SAALT), which is headed by Deepa Iyer is another innovative organization in Washington DC. A second-generation advocacy group which takes on the persona of a larger South Asian identity, it tackles analysis and advocacy around immigration, hate crimes and social justice issues. Its members have testified before the House of Representatives Immigration Subcommittee about immigration reform, and the UN Special Rapporteur on civil and immigration rights.

Indian-American Organizations Reach Out

In 2008, 34 South Asian community organizations from 12 regions throughout the United States announced the formation of a National Coalition of South Asian Organizations. SAALT created the National Action Agenda, which lays out a policy platform for policy makers. Says Deepa Iyer: “It came about as a result of our recognition that issues affecting South Asian communities must be included in policy-level discussions in order to promote social justice.”

Yet this more expansive approach to a larger shared identity and coalition building didn’t happen in a day. Narender Reddy believes political activism or informal lobbying was not well known in the Indian American community for a long time. He says they came together to some extent to oppose Congressman Dan Burton’s (R-Indiana) efforts in the mid-90’s to get the House to pass a resolution, year after year, censuring India for its so-called ‘human right violations’ in Kashmir and Punjab.

“This made our community realize the need to have political power/awareness,” he says. “Ultimately, due to our lobbying efforts, his efforts to introduce a house resolution censuring India failed time and again. Over the period, the Congressman ceased taking a stand against India in the House.”

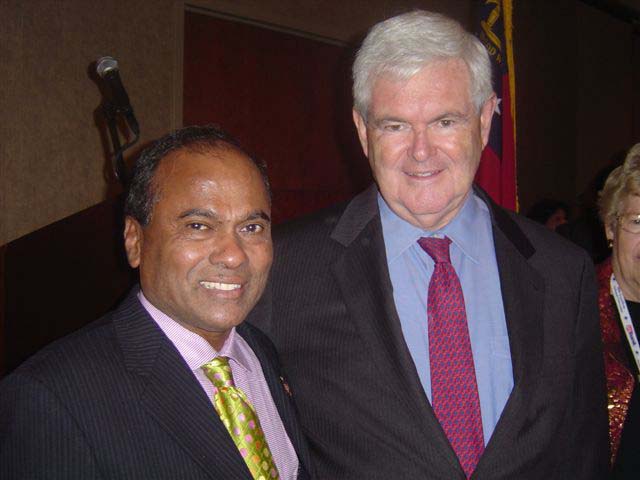

Reddy believes that more than organizational lobbying, it is the efforts of individuals across the US whose personal relationships and financial support of elected representatives have a greater impact in lobbying and obtaining their support for causes important to India and Indian-American community.

“Due to my personal friendship with Senators Johnny Isakson, Sen. Saxby Chambliss and Congressmen: John Linder, Tom Price, and Lynn Westmoreland, I was able to get their total support for India interest legislations over the years, especially, US-India Nuclear Deal,” says Reddy. He notes that for the first time all the three Congressmen from the Georgia delegation co-sponsored the bill in the House, a rare occurrence.

Indeed, there have been several names in the political success story of Indians, both in the Republican and Democratic parties. The roll-call includes names like Gopal Khanna, Akhil and Piyush Agrawal, Danny Gaekwad , Harry Walia, Dr. Vijaynagar,

Dr. R. Vijay, Dr. Raj Vatikutti, Bharat Bhargava and Rana Suresh on the Republican side. Notable Democrats include Ramesh Kapur, Rajen Anand, Dr. Mahendra Tak, Vinod Khosla, Sunil Puri, Shekar Narahisiman, and Subodh Chandra.

Dino Teppara, who has seen the Indian-American action in Washington DC, feels that in a broad sense a lot of lobbying is being done as there are lots of Indian-American organizations, lots of interest and photo ops as well as receptions which are attended by Congressmen. However, he feels that in spite of Indian-Americans being very wealthy and well-connected, there are no serious discussions, no history of philanthropy and the organizations have negligible budgets for lobbying.

“There’s no full-time lobbying – .we’re not at the stage to do that on the Hill,” says Teppara. “The American-Jewish community raised 125 million dollars last year – there is not even one Indian group which raises even $ 1 million. We have a lot of potential to do lobbying; we have a lot of potential to be powerful. The reality is that when there’s no money you can’t do anything.”

He points out that there’s also a generational divide between first generation groups and the newer ones created by the second-generation, often mired in jealousy or controversy. He says, “We do not have a history of giving money to our own community – because of this, the whole community suffers. Let the second generation run things. That’s not happened – the torch has not been passed.”

Yet there’s hope in all the young Indian-Americans who are now working in Washington, learning the ropes of networking, advocacy and lobbying. They even have a Desi Power Hour – more of a gathering than a club where young Indian Americans who are in politics get together to socialize. “Hill Staffers, political consultants, young professionals, and members of the Administration of both parties come. It’s a great event with a turnout of 50-75, once a quarter,” says Contractor.

Lobbying for Indo-US relations and that done for purely Indian-American interests sometimes overlap. With healthcare becoming such a vital issue in America, the lobbying done by AAPI, the powerful group of Indian physicians looks after not only their own interests and those of international medical graduates, but increasingly has a say in the healthcare debate in America.

Ajeet R. Singhvi, MD, the president of AAPI, attests to the ever-increasing visibility of Indian-American physicians and in the future, he says, one out of every four or five will be a physician of Indian origin.

Under his watch, AAPI has established a legislative office and member supported Political Action Committee (PAC) in Washington, DC, chaired by Dr. Krishan Aggarwal. “Now that Indians are getting into the political field, we will definitely be making a mark.” says Singhvi. “It is my earnest hope that our increased political activism will result in at least ten members of Indian origin in the U.S. Congress within the decade.”

According to Teppara, who serves as the AAPI Director of Legislative Affairs, the organization has been active in legislation in increasing residency slots as it’s predicted there is going to be a shortage of 150,000 doctors in the next 15 years. Through AAPI’s efforts for a renewal of the Conrad 30/J-1 visa waiver program for International Medical Graduates, the waiver has been renewed through 2012. Other lobbying efforts have resulted in legislation allowing medical students to defer payments on their federal student loans, reversing legislation which had been passed by Congress in 2007.

The Asian-American Hotel Owners Association ( AAHOA) is another organization which has understood the importance of lobbying to impact the issues which affect hoteliers in the US. Anurag Varma represents the interests of the organization whose membership owns and operates 40% of all hotel properties in the United States. Through a Lobby Day, AAHOA hoteliers spend a day in Washington, visiting over 150 different congressional offices to talk about the issues. “AAHOA has the head office, they have a lobbyist, they have the resources to get everyone organized, to be prepared,” says Varma. “That is the infrastructure that you need to be able to get the voices of the individual Indian Americans to Capitol Hill.”

The newest kid on the block, and perhaps one of the most effective, is HAF – Hindu American Foundation. This organization built by all second generation Indian-Americans is savvy about reaching the power elite of Washington DC in order to change the way Hinduism is viewed in America. HAF has set up an office in Washington DC with full-time staff and have built up sweat-equity by really working on meeting and discussing policy with Congressional staffers.

One of the first efforts of HAF led to the acknowledgement of Diwali by Congress. “Since our inception, we made recognizing Diwali one of our main goals, and in 2007, this became a reality with HRes 747 and SRes 245 (House and Senate Resolutions respectively),” says Ishani Chowdhury, Director of HAF. “It is an iconic first step in having younger generations feel a sense of pride about their faith and holiday, which is just too often ignored by the media. For older generations as it is a reminder that their efforts in instilling their faith have not gone in vain.”

HAF, under its president Dr. Mihir Meghani, gradually took on issues of hate speech, discrimination and defamation, in the process interacting with leaders in public policy, academia and media about Hinduism and global issues concerning Hindus.

“The greatest achievement in the realm of legal advocacy is getting a progressive Hindu American voice articulated and heard,” says Suhag Shukla, who is legal counsel for HAF. She points out that HAF has successfully presented an authentic Hindu American perspective before the US Supreme Court, several State Supreme Courts as well as many lower federal and state courts.

Dealing with Congress and other branches of government is a time-consuming process and one of the realities of grassroots lobbying. “It takes hours to prepare for and arrange meetings with the appropriate staff members, who will likely grant no more than 15 minutes of their time, of which you have five minutes to present your case,” says Ishani Chowdhury. “Then there are hours of follow-up. Before a Congressman signs off on anything, it has to be approved by layers of his people -legislative assistant, press aid, legislative director, chief of staff, and if there is disagreement, the response may be less than favorable.”

Working on the nuts and bolts of forging relationships is always hard but slowly the Indian-American community is getting the hang of it. At the same time, away from the Beltway, there are political activists who actually motivate the community and get them to use their political clout with their elected Congressmen. Indeed, if you are Indian and have access to email, you are likely to have heard from Ram Narayanan, a dedicated grassroots advocate who keeps a vigilant eye on Indo-US relations and gets people involved in the political process.

Narayanan heads US-India Friendship (http://www.usindiafriendship.net/ ) and he and his wife ensure writing to senators and congressmen is simplified by providing tips and form letters to over 15,000 subscribers. “Every representative in Congress must be made aware that funding support as well as support at the voting booths is at least partly contingent on the voting records of congressmen and women in matters relating to US-India relations,” says Narayanan.

The nuclear deal has indeed been one of the shining moments of Indo-US relations, and no matter which community leader or organization you talk to, almost every one of them wants to take credit for making it a reality.

“Every success has a thousand mothers,” says Varma cryptically. Yet as he points out, you cannot give credit to any one person or any small group of Indian Americans for being the driving force of success in the Indian American community.

While there is an India Caucus in both the Senate and the House of Representatives headed by India-friendly politicians, the reason for their success is that Indian Americans have benefited from a widespread perception of being good Americans that needed to have their cause supported, says Varma.

He also gives credit to the many first generation Indian-Americans who did something new and radical – become politically active and adapt to the American way. People like Mike Patel, Narender Reddy, Swapan Chatterjee, Sant Singh Chatwal and Dr. Bhupi Patel have spent many years in nurturing relationships with the Washington power players, not only through financial donations but by building trust. “And the fact that these individuals used their relationship to the betterment of larger community causes and US-India causes is actually a tribute to them,” says Varma.

Many successful Indian-American physicians and entrepreneurs have used their own time and money to forge friendly personal relations with Congressmen and Senators. Over the years Chatwal, for example, has had a close relationship with the Clintons and other power players, and these have all helped when it came to gaining acceptance for the Indo-US nuclear deal.

Indeed, Chatwal, who is the Chair of Indian-Americans for Democrats, used his connections to throw a big event in Washington in May 2006 to promote the Indo-US nuclear deal, and over a dozen US senators and 48 Congressmen showed up. Recently he was awarded the Padma Vibhushan, India’s second highest civilian honor – and the recommendation came reportedly came from the highest office in the land – that of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.

Many Indian-Americans took their own money and time and used their own personal connections to do the lobbying which is not counted as part of the money for lobbying, says Andersen. “They do it on a volunteer basis but they’ve become quite sophisticated at that. That makes them a bit different from the Jewish community where they have a somewhat formalized lobbying effort. One of the complaints I’ve heard – and to which there is some truth is that they are not as unified so there’s less of a collective effort. But where they make up for it is in their own individual contributions.”

As the second-generation heads into policy and politics, the effect of desi lobbying efforts is bound to increase. Even as young Indian-Americans create their own organizations, it is interesting to see that age-old ethnic associations and even religious institutions are also becoming tangentially involved in the lobbying process. These were some of the earliest institutions to take root in America – and now they are getting added roles.

The various regional organizations ranging from the Tamil Sangam to the Gujarat Association often invite local and national political leaders as guests and keynote speakers to their national conventions; the gurudwaras and temples too become venues for linkages, providing a space for social and political interaction, besides the religious aspect. “These are the binding factors you need to have any collective action,” says Andersen.

In fact, the new builds upon the old. Gopal Raju’s IPCA, which placed young Indian-Americans in the political field, may no longer be there but the ones who benefited from it have now started The Washington Leadership Program (WLP), which seeks to continue his legacy by introducing college students into the offices of Congressmen and Senators. Former Congressional leader Richard Gephardt has called it “one of the best programs of its kind on the Hill.” Over 170 young people have benefited from this, getting their first taste of political advocacy.

Using a mosaic of old and new networks, ancient and modern tactics, as well as their Indian genes and American experiences, Indian-Americans are finally headed on the Yellow Brick Road to the power citadels of Washington.

© Lavina Melwani

The Power of Indian-American Networks

Dr. Thomas Abraham takes you through the years of political action…

Since students were the first Indians to come to America, the first predominant Indians groups were the University based student associations. With the change in immigration laws in 1965, the doors were open for Indian engineers, doctors, nurses and other professionals. The first major community-based group was initiated by new immigrants in New York with the formation of the Association of Indians in America (AIA). In the meanwhile, Chandra Jha of Chicago revived the old India League of America in Chicago. AIA also was able to get Asian Indians listed as a minority under the Asian and Pacific Islander category.

By early 1970s, there were about 15 organizations in New York alone. In a unifying effort to bring all these groups together, the Indian Consulate in New York took the initiative to form a Joint Committee of Indian Organizations with the help of the most active Indian group at that time, the Indian Club of Columbia University. Four students from Columbia University, Thomas Abraham, Himanshu Jain, Ajai Goyal and Vidur Seth loaned 100 dollar each to put up the initial fund for the Joint Committee activities, with an account operated separately under India Club of Columbia University.

With the success of the Joint Committee in reaching out the various community groups, there was move toward starting the Federation of Indian Associations (FIA) in New York. The FIA New York was officially launched in 1978, and by the 1980’s, it had over 200 member associations as its members, including AAPI and AAHOA.

The Indian American Forum for Political Education (IAFPE) founded by Dr. Joy Cherian in Washington, DC., became a catalyst for political action. President Reagan appointed Dr. Joy Cherian as Commissioner of EEOC in 1987, the first major sub-cabinet level appointment on a federal level. Dr. Cherian served under three presidents, President Reagan, President Bush and President Clinton.

Two other appointments under the Bush administration were Bharat Bhargava as Assistant Director of Minority Business Development Authority (MBDA), and Dr. Sambu Banik as Executive Director for Presidential Commission on Mental Retardation. The Clinton administration appointed Dr. Arati Prabhakar as the Director of National Institute of Standards and Technology Neil Dhillon as the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Transportation and Dr. Rajen Anand as Executive Director of Center for Nutrition Policy under USDA.

President George Bush Jr. administration appointed Bobby Jindal as the Assistant Secretary of Health while Gopal Khanna was appointed as the Chief Technology Officer of Peace Corps,and Karan Bhatia, Deputy Under-Secretary in the Department of Commerce. As we all know, Bobby Jindal went on to become the Governor of Louisiana.

In the 1990s, several new national organizations emerged with new groups of people involving in them. The young Indian American professionals formed Network of Indian Professional (NetIP) in the mid 1990s. Around the same time, The Indus Entrepreneurs (TiE) was formed in the Silicon Valley. Another group initiated by Dr. Krishna Reddy of Los Angeles, Indo-American Friendship Council, has been actively campaigning with congressmen and senators for better India-U.S. relations.

The Obama Administration has appointed many more Indian-Americans in high positions and the future looks promising.

(Source – Dr. Thomas Abraham of GOPIO)

This article first appeared in Khabar