Sakti Burman’s Contemporary Indian Art

The phone line crackled across the Atlantic Ocean. I was in New York, and renowned artist Sakti Burman was in his country house in Anthe, near Toulouse, 650 km from his home in Paris. Thanks to satellite communications, the dialogue was as crystal clear as if we were sitting in the same room. Burman, 74, told me his 13-year-old grandson was with him, while his wife and the other grandchildren had gone for their daily walk.

“We live in a priest house, and there is a church and a graveyard,” said Burman in his halting English. “Next to it is a huge field of sunflowers – it is very beautiful – in a few days all around it will be Van Gogh sunflowers, as painted by the Impressionists.”

The artist, whose exhibition Enraptured Gaze was recently shown in New York at Aicon Gallery, has lived a lifetime in France, a good 54 years. I told him, “You’ve lived in Paris for so long, you probably speak better French than you do English.” To which he laughingly replied, “I speak both the same way – none of them too good! I can manage with both of them but I can express myself better in French.”

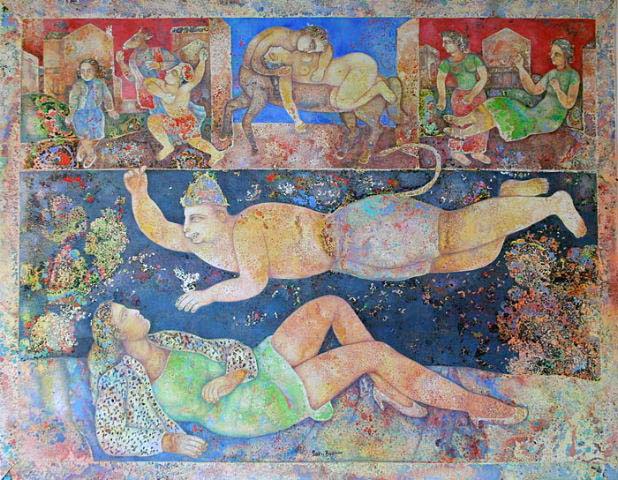

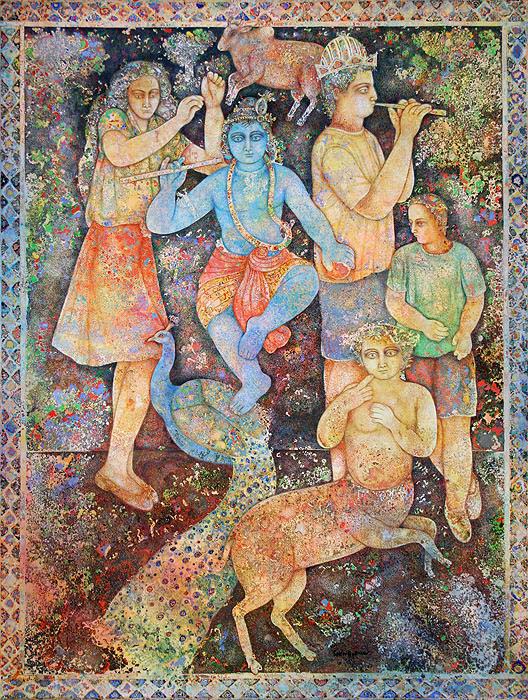

Language may not be Burman’s strong suit but he soars and flies to the moon through his wonderful paintings. A brush in his hand is a passport to poetry, literature, love and the highest aspirations of humanity. As if by magic, mythical creatures, Gods and humans appear on his canvases which evoke ancient tempered frescoes. There is much beauty, much joy in these incandescent paintings, and improbable stories from the past blending with contemporary tableaux.

Leaving Calcutta

What has the journey been like for a man who left India at the age of 20, and what memories does he carry of his homeland? He recalls that growing up in Calcutta, his knowledge of art and artists was very limited. In 1961 when he entered art school, art as a profession was not looked upon too kindly; art was something one could do only when one had everything to live with. He says, “My father never discouraged me but many parents, including mine, would have been happy to see me as a doctor or a lawyer.”

Burman has a home in Delhi but he still feels very connected to Calcutta even though he hasn’t lived there for decades. In fact, some of his happiest memories are those as an art student living in a Calcutta hostel, while he studied at the Government College of Arts and Crafts. Bag on back, he would travel around the poorer parts of the city with his friends, sketching and painting watercolors. He recalled one exhibition that came in the 50’s of Soviet Communist art and the buzz it created: “It was fantastic to see the huge queues, people came from the villages and it created a great enthusiasm among the art students.”

Burman went on to study at Ecole Nationale des Beaux Arts in Paris. While he is the first one in his family to take on art as a profession, his wife is the noted French artist Maite Delteil, and his daughter Maya Burman as well as his niece Jayasree Burman (who is married to artist Paresh Maity) have also made a name for themselves in the art world. He says that all the people in his family were very artistic minded and recalls that his mother, aunts and sisters created thattas which were full of imaginary things, almost like tableaux.

Living between two cultures, Burman has blended both, and is equally at home in the streets of Paris and Delhi. He admits that he thinks in French because he is speaking that language all the time and is as often in rustic French villages as in sophisticated Paris.

Sakti Burman’s Life and Times

He believes that because of what he experienced in his childhood, the way he grew up, Indian culture has infiltrated his life: “My Indian culture is still there and I don’t think I have neglected or thrown away the culture of where I am living,” he says. “Every culture is rich and every culture also has something to be criticized for.”

The villages of his youth, the Indian hues of pinks, blues, greens and oranges, the spirituality, the Indian miniatures have all stayed with him.

“One shouldn’t forget one’s roots. I never thought that I was forcibly giving up anything,” he says. “I hope I have gathered things from others too – this is what I always felt and I always feel.” Besides all the Indian influences, he was also been deeply affected by the art of Matisse, Bonnard and Picasso and he hopes these inspirations are all mixed up in his work.

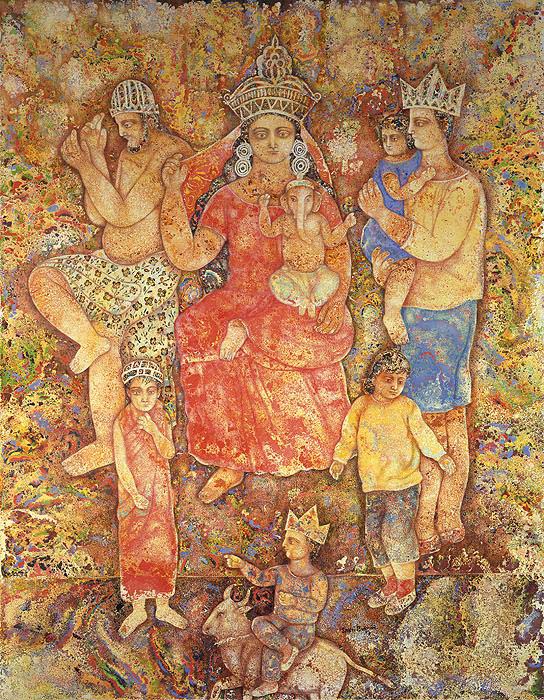

Indeed, cultures, colors and other worlds constantly merge in his work, an example being Ganesh Janani wiith Ganapathy, Evariste and Estelle (2008), which would be at home in a church or a temple. His work reverberates with fables, magic, lyricism and many European influences, mingled with Indian colors, gods, humans and mythical beasts. Ganapathy, Krishna, Hanuman and Durga wander through his fantastic imaginings, far away from Indian landscapes.

There is such a benign dream-like quality to his canvases, how does he keep harsh reality – the poverty, the wars and violence – mostly out of his art?

“Yes, sometimes I ask myself that too,” he says, and then proceeds to tell me about his early life. Born in Calcutta, he lived till the age of seven or eight in Bidakot, a small village in Bangladesh, a village which no longer exists. He remembers the lush overgrown vegetation and the overflowing ponds of this forgotten place. “I can see my sisters, my cousins, my relatives decorating the floor for the festivities for the Puja,” he says. “In the rainy season the water used to come till our home and we had to go from one house to another by boat.”

Sakti Burman: Past and Future

It was at that time, in 1943, that the terrible famine of Bengal took place and he also lost his mother. He did not feel that loss profoundly because sisters and aunts took him under their wing. “The memories of that time are so important to me,” he says. “In spite of all the difficulties, I was taken care of by other people in the family. I think all that stayed with me, and I always try to be a little bit optimistic about life.”

He adds: “I feel that the horrible thing of life, the miseries and everything are there but I have the hope that one day they might disappear. In the end, hope is the only thing that you can hold on to and continue living.”

What does he hope viewers will take away from his work? He says, “If people look at my paintings and have a feeling of happiness, its good enough for me. The pain is there but if you can feel happy for a while, what else can you want?”

It is this eternal optimism that he brings to all his work, a constant hopeful search for the indefinable. He says: “The one thing an artist must do is be very truthful with himself; he must do things which he thinks are the truth, even if we don’t know what the absolute truth is. We are always looking for the unknown, this is the way an artist lives.”

. He remembers a tale from the Upanishads, simple yet profound, which he had heard many years ago: the Gods had a powerful secret which they didn’t want human beings to know because once they acquired it, they would become Gods themselves. So the Gods thought of hiding this secret in the sky and even in the underworld, but knew man was intelligent and would find it. So they decided to hide the secret in the head of Man himself.

“This is why we are always looking for something which we don’t know, we are always running for that unknown thing,” says Sakti Burman. “It’s a perpetual searching – so you see it’s all in our heads. I’m not someone who is jumping from one thing to another. I am trying to follow a line and trying to go deep within myself. Everyone has their own way of looking at things, and this is the way I see things.”

A SAMPLING OF SAKTI BURMAN…

In Artist and Model (2008), Sakti created an allegory of his French-Indian life as a painter. Sakti painted himself sitting at his easel on the right wearing spectacles and Western attire, and in a mirror-image on the left he wears a traditional Indian garment and sits on a peacock. In this painting-within-a-painting Sakti has composed an exact duplicate of the nude model standing before him. In a nod to the French realist Gustave Courbet’s L’atelier du peintre, allégorie réelle (The Artist’s studio, a real allegory, 1855), Sakti has surrounded himself with his muses and admirers, including family members, an Indian mythological figure on a horse, a reclining classical woman and assorted cherubs. The inspirational roles of all his muses is marked by colorful flowers in their hair. The art world today is richer because, as this allegory of painting demonstrates, Sakti Burman has embraced two cultures and created from them his own unique international vision ―his enraptured gaze.

(Credit: Aicon Gallery)

Photos credit: Aicon Gallery

© Lavina Melwani This article was first published in The Hindu in 2009.