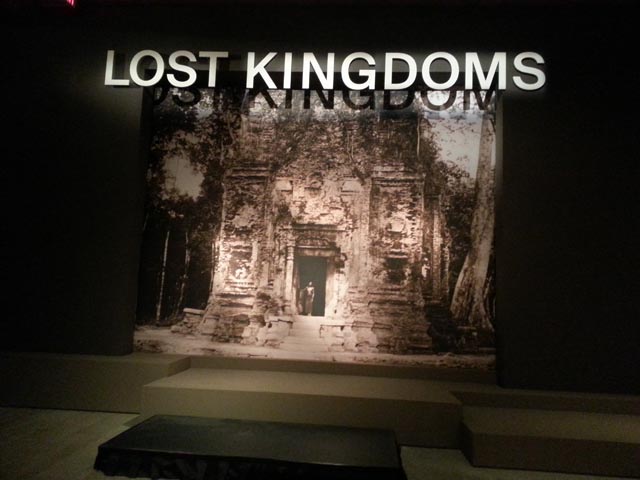

Lost Kingdoms of Early Southeast Asia at the Met

Photos: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Thierry Ollivier

Sometimes entire worlds disappear yet art survives and tells us the stories which would have remained untold. ‘Sivapada’ (Shiva’s Footprints), a wonderful sandstone sculpture by unknown artists in Northern Cambodia in the 7th-8th century, shows us the imprint of Hinduism on vanished Southeast Asian cultures of the first millennium. That age also saw a major flowering of Buddhism via India with a rich treasure-trove of art.

Fabulous life-sized images of Shiva, Vishnu, Ganesha, and a pantheon of Hindu Gods have been unearthed in Southeast Asia and they look not quite like the deities as we know them in India. The features seem Southeast Asian, the headgear is different but there is no doubt as to their Supreme Power. Though the inspiration is Indian, local aesthetics and local artists have given these vibrant, exquisite masterpieces of Hindu and Buddhist icons a flavor all their own.

The worship of footprints is an ancient Indian practice that was shared among Hindus, Buddhists, and Jains. In fifth-century India, shrines dedicated to holy footprints, predominantly of Vishnu (vishnupada), were widespread. Shiva’s footprints (shivapada) in India are extremely rare, but texts confirm their existence, especially the Skandapurana, which describes them marking Shiva’s sacred geography. (wall text)

The Footprints of Shiva

For the first time, the cream of the cream of the treasures have been gathered at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York: – ‘Lost Kingdoms – Hindu Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia’ which brings to light this long-forgotten world. The exhibition (April 14 – July 27, 2014) is the first international loan exhibition with over 160 sculptures from the cultures of Pyu, Funan, Zhenla, Champa, Dvāravatī, Kedah, and Śrīvijaya.

“These early states represent the beginning of state formation in Southeast Asia, and their archaeological footprints broadly define the political map of the region today,” says Thomas P. Campbell, Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “The surviving corpus of early religious art from these kingdoms, much of it spectacular in scale and often sublimely beautiful, is our principal window into these cultures.”

This four-armed form of the elephant-headed son of Shiva and Parvati is among the most sophisticated early Cham sculptures. Ganesha is represented as the embodiment of the asceticism exemplified by his father, displaying the third eye on his forehead and wearing the tiger skin of an ascetic sage (rishi).

India: Exporting Culture & Spirituality

As he points out, the exhibition traces the interactions between South and Southeast Asia largely through the circulation of Hindu Buddhist imagery throughout the Diaspora, revealing the flow of ideas, artistic styles and religious and political structures across the region: “Imported concepts continued to evolve in their new setting, displaying substantial cultural and political transformations as they were absorbed and appropriated to suit the needs of the host cultures. It is the metamorphosis of Indian imagery into a Southeast Asian guise that defines the art’s unique contribution.”

John Guy, Curator of the Arts of South and Southeast Asia at the Met who curated the show and also edited the catalog, walked us through the galleries. The masterpieces, many of them monumental, have been brought together by negotiating loans from six Southeast Asian countries, Paris and the U.S. Many are national treasures and have never traveled outside their home countries before.

In fact, Myanmar has made its first ever international loans to this exhibition, including the Throne Stele (4th century) – it is the oldest religious object surviving from Southeast Asia, and has Hindu and Buddhist emblems on the reverse sides, showing that the two faiths enjoyed royal patronage concurrently in early Southeast Asia.

As described in the Bhagavata Purana, the youthful Krishna miraculously raises Mount Govardhan, near Mathura in northern India, to protect the villagers and cowherds from a great rainstorm sent by Indra. The sculptor of this image, active in the Phnom Da workshops, clearly understood the essence of his subject.

The Indianization of Southeast Asia

This art tells a more expanded tale of the robust trade between India and Southeast Asia, and indeed, the first Brahmans and Buddhist monks who ventured to Southeast Asia traveled on merchant ships.

“The “Indianization of Southeast Asia – that is the adoption and adaptation of foreign, Indic ideas – fundamentally shaped cultural developments in the region, providing a conceptual and linguistic framework for new ideals of kingship, state and religious order,” observes John Guy.

The artworks were done under royal patronage, and the artists worked in workshops along with master artists. The majority of the works are in stone, with others in bronze, gold, silver, terracotta, and stucco. Among the masterpieces in the exhibition, there is a spectacular Krishna Holding Mt. Govardhana from the hill shrine of Phnom Da, in southern Cambodia; and there is a similar one also from the same region, now in the Cleveland Museum of Art. This Krishna myth, famous in the Bhagvatapurana, is rarely found in sculptural form in India. In fact, Guy observes that the Phnom Da sculptures evolved from a long-standing local tradition which surpassed any Indian prototypes.

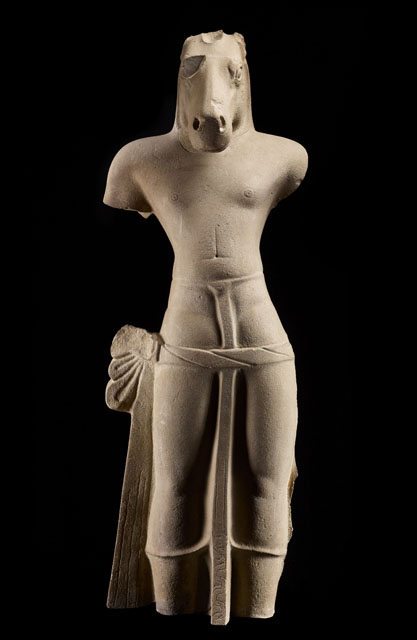

Kalkin is the future world savior, understood as the tenth avatar of Vishnu, who will appear in the form of a white horse to judge mankind. Vishnu appears in a number of early legends with a horse’s head, linking him to Vedic horse sacrifice. It is clear from the size and authority of this sculpture that it was worshipped as an important cult deity. It is perhaps not a coincidence that Kalkin Vishnu appears in early seventh-century Cambodia at precisely the same time as the bodhisattva Maitreya, his conceptual counterpart in Buddhism: both are worshipped as messianic saviors. (wall text)

Hindu Deities – Kalkin, Vishnu’s Future Avatar

Hindu deities from Brahma to Durga to Lakshmi are found in Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam. Another remarkable sculpture rarely seen in India is Kalkin, Vishnu’s Future Avatar, found in Southern Cambodia, near the village of Kouk Trap. Kalkin (“having or being a white horse) is the 10th avatar of Vishnu, who, it is said, will return in the next kalyuga as a white horse to judge mankind. From its compelling size and powerful physique, one knows this was an important deity.

An entire gallery is devoted to Shiva in his many forms, and to his consort – Devi, known as Uma in early Cambodia. There are many images of Ganesha: particularly endearing is one from the 8th century, from My Son in Vietnam. It depicts him as an ascetic like his father, with a third eye and wrapped in a tiger skin. His sacred thread is a snake and on his wrists are bracelets of snakes. Huge icons of Ganesha were found from Vietnam to Thailand, and Guy says, “These works bear witness to a cult that had assumed a prominence not see in Ganesha’s native India.”

Among the most beautiful images of the Avalokiteshvara from all of Southeast Asia, this savior stands on a pair of lotus blooms, his eyes downcast as he extends grace to devotees. He wears an elaborate diadem with the Amitabha Buddha prominently displayed. His left hand holds a lotus bud, evoking Padmapani, the lotus bearer, and his right holds an ascetic’s water vessel (kamandalu). (wall text)

Discovering the Buddha

The Buddhist art is an expression of state identity, represented by some of the most monumental works in the exhibition: stone Buddhas, sacred wheels of the Buddha’s Law, and narrative steles and reliefs. There is also a late seventh-century Avalokitesivara discovered in the Mekong delta of Vietnam, “arguably the most beautiful image of the Buddhist embodiment of compassion from all of Southeast Asia.”

‘Lost Kingdoms’ is an evocative story of the past, of how Indian influence spread far and wide. In those days, India was a hotspot for trade and culture, influencing nations. Could history repeat itself, I asked John Guy, half in jest. He smiled, perhaps half in jest too: “Well, look at all the Indian diamond merchants in New York! Look at all the Hindu temples being built here!”

This article was first published in The Hindu

Related Article:

Yoga – the Art of Transformation – Ancient Yogis in Contemporary America

Please rate the article, share & comment! Thanks.